Why “Greasing The Groove” Will Make You Ageproof

Here’s how greasing the groove will make you stronger, more muscled (a bit), fit, mobile and live a longer, healthier life. Do you have anything better to do!

Greasing the groove is quite simple — you just start moving in repetitive patterns, alternating between easy peasy and real hard. And the rewards are outstanding. Not only in the form of muscle, strength and leanness — but life itself.

Study after study has proved the benefits of consistent exercise—weight loss, improved mood and cognitive function, stronger bones and muscles (duh!), deeper sleep, and lower risk of heart disease and various types of cancer. Not to mention it can help you discover sex that’s off the charts.

So, why do so many of us don’t break a sweat?

If you haven’t found the proper incentive, I’ve got a biggie for you — life! And I’m not just talking quality of life, I’m talking living without spending the last decade bent over in a wheelchair drooling on yourself.

If exercise could be put in a pill, it would be the ultimate anti-aging drug. I can’t show you how to make an anti-aging pill, but I will show you what to do instead.

Here’s what’s covered:

- Why fitness predicts lifespan better than most things

- A sedentary lifestyle is deadly

- Fit people get 50% less dementia

- Exercise can improve gut health, and visa versa

- Muscle is a new vital sign

- Greasing the groove — choose the best exercise for you

- Intensity

- HIIT

- Exercise snacks (delicious but inedible)

- How to grease the groove

- Mobility and anabolic stretching

Let’s dig in…

Your Fitness Predicts Lifespan Better Than Smoking or Medical History

It’s obvious that if you can accurately predict people’s risk of death, then you at least have a chance of adopting interventions that can help them prolong their lives. The typical indicators that make such predictions include various lifestyle choices, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, and health factors, such as cancer or heart disease history.

Less obvious is what a study published in The Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences showed was a reliable predictor of death; in fact, more reliable than those typical biometrics. Strange but true — I’m referring wearable activity trackers.

As described by Medical News Today, the study examined more than 30 predictors of 5-year all-cause mortality (using survey responses, medical records, and laboratory test results) of nearly 3,000 U.S. adults between the ages of 50 and 84. Physical activity made up 20 of these predictors, including total activity, time spent doing moderate to vigorous activity, and time spent not moving at all.

Says professor Ciprian Crainiceanu, Ph.D., from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health:

“We’ve been interested in studying physical activity and how accumulating it in spurts throughout the day could predict mortality because activity is a factor that can be changed, unlike age or genetics.”

“The most surprising finding,” says lead author Ekaterina Smirnova, M.S., Ph.D., “was that a simple summary of measures of activity derived from a hip-worn accelerometer over a week outperformed well-established mortality risk factors, such as age, cancer, diabetes, and smoking.”

The wearable trackers designated death risk 30% better than smoking-related information did, and was 40% more accurate than using data involving stroke or cancer history.

The type of “wearable activity trackers” used in the study was not mentioned, but “activity” can be measured by many popular trackers available today such as:

- Fitbit Charge 3 Fitness Activity Tracker

- Motiv Ring Fitness, Sleep and Heart Rate Tracker

- Apple Watch

- Samsung Galaxy Watch

- Letsfit Smart Watch

A Sedentary Lifestyle Will Kill You Prematurely

In a study done at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, researchers collected information about frequency and duration of leisure time and physical activity for just over 23,000 men and women in Norway.

Data was collected three times in a 22-year period, with activity categorized as inactive, moderate (fewer than two hours per week), and high at more than two hours

Here’s what they found:

- People who had a low-activity lifestyle for two decades were twice as likely to die early than those who exercised the most.

- Those who were sedentary early in life (ie: sitting all the time), but then adopted an exercise routine of two or more hours a week still had an increased chance of early death, but it was not as large as those who never exercised or who stopped exercising.

The good news is that it’s never too late to restart, or even start at all. And the threshold of two hours of exercise per week can be everyday movements like taking the stairs more often—which a previous study has suggested can have surprisingly significant results—or getting off the bus or subway a stop early to walk the rest of the way to your destination.

Says lead study author Trine Moholdt, Ph.D., research fellow at the university:

“You can reduce your risk by taking up physical activity later in life, even if you have not been active before. The health benefits extend beyond protection against premature death, to benefits for the body’s organs and for cognitive function. I recommend everyone get out of breath at least a couple times each week.”

Fit People Are 50% Less Likely To Get Dementia

People who were fit throughout a 20 year study period proved to be almost 50% less likely to develop dementia than the least-fit men and women. That’s the conclusion of yet another Norweigen study that examined the records from a large-scale health study that had enrolled almost every adult resident in the region around Trondheim, Norway beginning in the 1980s.

As reported by the New York Times, the researchers pulled records of more than 30,000 middle-aged participants who had completed health and medical testing twice, about ten years apart, that included estimates of their aerobic fitness. They then categorized them by their fitness and how it changed over the decade. Some had started and stayed out of shape; they remained in the lowest 20% of aerobic fitness for the whole ten years. Others moved into or out of that group based on how their fitness level changed over time. The fittest few began outside of the bottom 20%t and remained outside that group for all ten years.

The researchers then checked records from nursing homes and specialized memory clinics to see which participants developed dementia during a 20-year follow-up period and if fitness affected their risk for the disease.

What they found was that fitness affected their risk for dementia:

- People who were fit throughout the study period proved to be almost 50% less likely to develop dementia than the least-fit men and women.

- Even more encouraging — those who had entered middle age out of shape but then gained fitness showed the same substantial reduction in their subsequent risk for dementia.

Check out the Norwegian University of Science and Technology’s Fitness Calculator, used by more than six million people worldwide.

Exercise can improve gut health

Alterations to the gut microbiota have been observed in numerous diseases, including metabolic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and irritable bowel syndrome, and some animal experiments have suggested causality between them; meaning, that your gut bacteria can cause such diseases.

Microbial diversity is generally considered an indicator of gut health. A diverse microbiota is generally better for enduring health. A less diverse microbiota is less capable at supporting health, and it comes as no surprise that loss of diversity has been associated with the onset of diseases such as those mentioned above, as well as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, type 1 diabetes, obesity and colorectal cancer.

OK, it’s clear that our gut bacteria strongly influences health outcomes, but how does exercise come into play?

A recent study published in Nature Medicine suggests that gut microbes play a role in exercise performance. Researchers identified a specific bacterial strain called Veillonella atypica that was dramatically increased in marathon runners after having run a marathon. This particular bacteria has the ability to break down lactic acid, which is the acid that builds up in muscles during endurance exercise. Makes sense, right?

Gastroenterologist Will Bulsiewicz, M.D. wrote that when the scientists transferred this particular bacteria into mice, the mice improved their treadmill run time performance. This exercise performance result was purely based on the presence of this microbe. Dr. Bulsiewicz conjects that Veillonella atypica may cause a similar improvement in performance behind marathon running, and may promote muscle recovery after vigorous workouts.

His parting words:

“Exercise is a good idea, regardless of whether it alters your microbiome. But that said, it’s nice to know that physical fitness also promotes gut fitness because strong guts translate into better health.”

Dr. Michael Lustgarten from the Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University confirmed the conclusions of the above study that specific bacteria can increase exercise performance, and then took it up a few notches.

He reported that high-functioning older adults that he studied had a more favorable body composition — including a higher percentage of lean mass and a decreased percentage of fat mass, and better physical functioning, including muscle strength — when compared with low-functioning older adults.

He and his team identified gut microbiome differences between these two groups, but such an observation, though important, doesn’t indicate causation. So, what they did was transfer fecal samples from the high functioning group to the low one, which showed causative role for the gut microbiome on obesity and immunosenescence (the gradual deterioration of the immune system brought on by natural age advancement.)

I’ve just touched on the importance of a healthy microbiome. It influences our health in nearly every way you can imagine. I encourage you to read some articles I’ve written about why a healthy microbiota is essential for healthy aging.

Muscle is new vital sign

Eurekalert summarized a review paper published in Annals of Medicine confirming the critical role muscle mass plays in health, citing studies demonstrating that people with less muscle had more surgical and post-operative complications, longer hospital stays, lower physical function, poorer quality of life and overall lower survival.

This is yet another study that adds to the growing scientific evidence that muscle mass should be a key factor in evaluating a person’s health status, especially if living with a chronic disease.

The review examined more than 140 studies in inpatient, outpatient and long-term care settings, and had one resounding conclusion:

Muscle mass matters!

Now, please understand that by “muscle mass” no one is referring to the Hulk; muscle mass does not imply massive muscles. In this case, muscle mass refers to a sufficient amount of muscle in order to move your body around, whether it be up and down off the floor, doing a push-up (maybe a pull-up), walk up stairs, walk up hills, etc.

The data show muscle mass can say a lot about a person’s overall health status, especially if living with a chronic disease. For example:

- A study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) showed women with breast cancer with low muscle mass had a 40 percent higher likelihood of mortality.

- Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) with more muscle spend less time on the ventilator — as well as less time in the ICU — and have a better chance of survival.

- People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who have more muscle experience better respiratory outcomes and lower occurrence of osteopenia or osteoporosis.

- In the long-term care setting, a study found that individuals with lower muscle mass had more severe Alzheimer’s.

(Go here for references to the above.)

“Muscle mass should be looked at as a new vital sign,” said Carla Prado, Ph.D., R.D., associate professor at the University of Alberta and principal author of the paper. “If healthcare professionals identify and treat low muscle mass, they can significantly improve their patients’ health outcomes. Fortunately, advances in technology are making it easier for practitioners to measure muscle mass.”

If you doubt what your mirror has to say about your muscle mass, you can get a body fat scale to measure it.

Yes, you could rely on the body mass index (BMI) as an indicator of good or bad body composition, but as I wrote in How Much Should You Weigh? Calculate Your Ideal Body Weight, BMI can be misleading since it doesn’t distinguish between muscle mass and fat mass. Low muscle mass can occur at any body weight, so someone who is normal weight may appear healthy, when they can in fact lack muscle.

If in doubt, test it.

Greasing The Groove — Choose the Best Exercise Regimen for You

story about David Kirkpatrick who at the age of 68 started sprinting for 21 minutes each week and lost 44 pounds. A friend suggested that David run “like I was five years old again”. So he chased a soccer ball that he kicked around at a beach.

At this point, it’s clear that muscle-building exercise is essential to live a long and strong life. People are living longer and remaining active for many more years than past generations. And the more fit you stay into your later years, the more years you’re likely to live.

- One study found that those with the highest levels of fitness at age 75 were more than twice as likely to live another 10 years or more compared to those with poorer fitness.

- Another study indicates that people who go for a run just once a week can reduce the risk of death from any cause by as much as 27%.

Naturally, jogging a few miles once a week isn’t going to get you in shape, but apparently it does have a significant impact on mortality. Moreover, if jogging isn’t your thing, any heart-rate-ramping exercise such as bicycling, swimming or those stationary aerobic machines found in most gyms will suffice.

When choosing an aerobic exercise, I suggest those gentle on the joints be shown preference so you don’t have to stop before your muscles and heart do because your joints are ready to quit.

Clearly, we face challenges with age. Science shows that metabolism changes, making it easier to gain weight and lose muscle, as we get older. Recovery takes longer, too. That means you need to keep up the intensity to maintain muscle and top-end fitness, and take proper care to quickly recover from those efforts.

I want to guide you in choosing some exercises, or routines, that can make a difference in robust aging. The four things to incorporate into your exercise regime are:

- Aerobic conditioning — this is the relatively slow and steady exercise at a pace that you’d be able to carry on a short-sentenced conversation.

- Anaerobic conditioning — this is sprinting-type, high intensity interval training (HIIT) exercises that leave you breathless and that typically work most of your major muscle groups.

- Resistance training — building muscle and getting stronger by lifting weights or bodyweight.

- Mobility training — Mobility is the ability to move freely and easily, while stretching is a key way to help achieve this. A quick image: think of how a child moves.

I’ve covered all four of these fitness components in my six-part series, The Functionally Fit Fast Workout, which I encourage you to check out. That said, I want to provide some thoughts here about:

- Workout intensity,

- HIIT,

- Exercise snacks,

- Greasing the groove,

- Mobility focusing on glutes and the posterior chain,and

- A 30-day plan.

Exercise workout intensity

If you’ve ever spent much time in a gym or hung around those who do, invariably you will hear that you have to train to failure on each exercise you do. If you’re squatting with a weight that you could only do ten times if a gun were put to your head, that’s the failure point. And it’s a ridiculous way to train.

I’m not saying that you need to put in effort, nor that training to failure is always wrong. What I am saying is that you don’t do it that way all the time.

So, how often to do a particular exercise movement to failure?

It depends, but as a rule of thumb: After you’ve consistently done resistance training for a few months, lift to failure just once per week.

There’s no generic amount, because it depends on many factors, such as age, training experience, the magnitude of the load (percent of one rep maximum is being lifted) and type of exercise (single muscle vs compound muscles being exercised, free weight vs machine).

Of course, workout intensity doesn’t only refer to performing an exercise till failure. There are many ways to measure intensity, such as HIIT.

High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT)

As with the topic of the microbiome, I’ve written quite a bit about HIIT, which you can scroll through here.

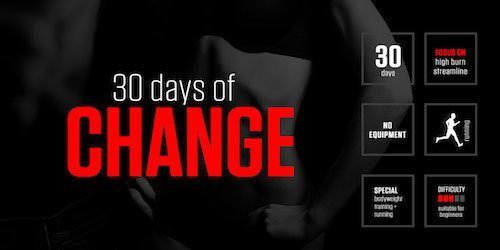

Recently, however, I came across a story about David Kirkpatrick who at the age of 68 started sprinting for 21 minutes each week and lost 44 pounds. A friend suggested that David run “like I was five years old again”. So he chased a soccer ball that he kicked around at a beach.

What occurred to David lines up with the research. Just small bursts of intense physical activity like sprints can supercharge your weight loss—as little as 8 seconds to 30 seconds of all-out effort at a time, according to one review of the literature.

A recent meta-analysis found that people who engaged in sprint-interval training (exercise equal to or higher than your VO2 max) lost 29% more bodyweight than those who engaged in continuous moderate-intensity exercise. So, it makes sense that adding chasing after a soccer ball to his routine would help boost his weight loss.

A study published in the ACSM Health and Fitness Journal laid out the benefits of a 7-minute workout, using a mix of bodyweight and high-intensity interval training. While this method incorporates full-body moves, the high-intensity nature of David’s seven minutes of sprinting follows the same principle.

And if getting fit and losing weight isn’t sufficiently motivating, one study after another show health benefits ranging from lowering your risk of cancer to boosting your brain function.

So, what’s to stop you?

Injury!

Assuming you can reach deep enough to push yourself, if the HIIT you do puts undo stress on already compromised joints, or untrained, unready muscles (think hamstrings), you will inevitably pay a big price doing something like sprints.

You must start slowly. And if you aren’t under 40 or already have a running background, consider doing your HIIT with a bike, or swimming, or calisthenics or simply power walking up a steep hill.

By the way, limit your HIIT to twice per week, unless you’re being recruited by the International Olympic Committee.

Exercise Snacks (Yum)

“Exercise snacks” is a delicious turn of phrase I read about in a GQ article about making exercise easier. Yes, we’re going from puking with HIIT to snacking with short bursts of bite-sized exercise.

The idea here is to divide the hour-plus time you might usually exercise in the morning or evening into two or three smaller exercise time frames done throughout the day. The value of this approach was underscored by a 2014 study, which showed that three smaller sessions of physical exercise (around 12 minutes each) were more effective in lowering blood sugar—and keeping it lower for longer—than one 30-minute session.

In effect, rather than gorging on one big meal (exercise session), you snack on a smaller bit of exercise throughout the day. A few exercise routines suggested by GQ:

Warm-Up:

- Jump rope or jog in place — 1 minute

- Dynamic leg swings — 16 reps (alternating legs)

- Knee hugs — 16 reps (alternating legs)

- Hip circles (on all fours/in a tabletop position) — 8 in each direction

- Bird-dogs — 5 each side

- Cat/cows — 5 reps

- Running Snack

Easy Option:

- Run 200 meters

- Walk for 30 seconds

- Run 400 meters

- Walk on incline (1.5-4.0) for 1 minute

- Repeat 3 times

Hard Option:

- “Deadmill” sprint for 15 seconds

- Rest for 45 seconds

- Repeat 4 times

- Rest 2 minutes. Do 5 more reps.

OR

- Incline between 8.0 and 12.0, speed at 8.0

- Sprint for 20 seconds

- Rest for 40 seconds

- Repeat 4 times

- Rest 2 minutes. Do 5 more reps.

- Mobility Snack

- Side-lying T-spine sweeps — 5 each side

- Seated T-spine reaches (up, side, straight) —5 each way

- Lying hip swivels — 10 reps

- Walking inchworms — 8 reps

- Spiderman pushup — 10 reps

- Single-side elevated plank — 8 each way

- Jump rope — 3 mins

- Weights Snack

- Deadlifts — 8 reps

- Bent over rows — 8 reps

- Renegade rows — 8 reps (alternating arms)

- Mountain climbers — 30 secs

(Repeat above four exercises) - Runner’s deadlifts — 8 reps

- Side lunges — 8 reps

- Shoulder presses — 8 reps (alternating arms)

- High knees — 30 secs

(Repeat above four exercises)

Moving through these shorter but more frequent bouts of exercise will help with greasing the groove, and it’s about time that I explain what that is.

Greasing the Groove Like the Russian Military Does

To me, “greasing the groove” is similar to that widely touted theory, highlighted in a 1993 psychology paper and popularized by Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, which posits that anyone can master a skill with 10,000 hours of practice.

Maybe yes, maybe no… but one thing for sure is that, as fitness blogger John Fawkes puts it:

“To become a better pitcher, you have to pitch a lot of baseballs. To become a better archer, you have to fire a lot of arrows. All of these motor patterns are skills, and skills need to be practiced.”

Ergo, if you want to become better at some exercise, you have to practice it a lot — grease the groove — and in order to do that, you have to do it with low intensity so that the exercise produces no significant amount of fatigue.

Obviously, this is the opposite of HIIT or exercising with intensity, but it’s not contradictory. The whole point of greasing the groove is to better prepare yourself for performing the same (or similar) exercise with intensity.

For example, say you want to get stronger with the squat, or bench press. You still program in your usual resistance training (weights or calisthenics), but you also to many sets of low repetition “free squats” (no weight) or push-ups throughout the day, several days per week. As long you keep the reps well below failure, like 50% of your maximum effort, and let your time between sets be long, like an hour, greasing the groove will not have much of an impact on your more intense exercise sessions that use the same muscle groups.

Don’t Forget About Mobility

I would argue that the older we get, the more important is our mobility work. You have to work to stop letting gravity collapse our spine, lean us forward and knock us to the ground. Certainly, strong muscles help, but let’s do both — build muscle and gain mobility with anabolic stretching, particularly as it applies to two very much ignored parts of our body, the glues and posterior chain.

You know what glutes are — they’re those two orbs midway down your backside when you were young that are now sliding down toward your heels. The “posterior chain” is a group of muscles on the posterior of the body: the hamstrings, erector spinae muscle group, trapezius, posterior deltoids, and, yes, the glutes as well.

Writer Kells McPhillips penned an article about anabolic stretching as an excellent way to improve mobility. She cites the work of Peter Tzemis, trainer and founder of TzemisFitness, and Phil Timmons, a program manager at Blink Fitness.

Peter Tzemis maintains that anabolic stretching essentially “bulletproofs your body” by replacing static stretching with a more active alternative. This is done by adding a light weight to your stretching posture and, he says, the benefits change entirely:

“The key thing is that you’re not really ‘stretching’ the way you do with most static stretching. You’re resisting the load in the stretched position.”

For example, lie down on a bench with one light dumbbell in each hand. Extend your hands out to your sides so that they’re perpendicular to your body, thereby putting some tension on your chest (pectoralis major muscles). Let the weight pull down your arms and stretch your chest. Two things will happen simultaneously: your muscles will activate and you’ll feel a stretch as a result of the pull of the muscle.

Phil Timmons says that anabolic stretching falls under the umbrella of “isometric concentration”—or exercise that involves static holds. Here’s how he describes it:

“Isometric contraction is one in which the muscle is activated, but instead of being allowed to lengthen or shorten, it’s held at a constant length. Anabolic stretching is a way to stress [the] volume of your muscular cells in order to grow in size. It’s leveraged in the same way that we do slow tempo training to gain hypertrophy (increasing the size) of the muscle.”

Now I want to get back to that long ignored posterior chain, and show you a video of applying anabolic stretching to make yours more mobile, stronger and bullet proof:

30 Days Of Change

Want a simple program you can immediately follow that can kick-start your entry (or reentry) into exercise?

It’s free and available with just one click.

The 30 Days of Change program from Darbee is designed to change your exercise habits, as well as the way you look and feel, in one fast month. Assuming you have a body, you need no equipment. Different daily programs will ensure that your body doesn’t adapt to the same routine so you’ll see progress a lot sooner than with any other program.

30 Days of Change is designed for weight loss and getting you tones. Depending on your present conditioning, it might be pretty intense, but it keeps the day-to-day routines balanced and just hard enough to keep your body responding to the challenge and changing for the better.

A different daily regimen helps you get the best results for a given amount of time. This program includes a lot of outside cardio so you have to be prepared to get outside from time to time and walk, jog or run. Some days consist of two parts, bodyweight and cardio routines – you can do one after the other or do one in the morning and one in the evening.

Check it out:

Your “Greasing the Groove” Takeaway

I covered a lot of material. First I wanted to emphasize that you must exercise regularly if you want to prevent the inevitable chronic disease that will kill you. We don’t die of old age, per se, but from some debilitating condition or disease.

Making your heart and muscles stronger through exercise goes a long way to pushing back the clock.

Remember these five things:

- Measure what you’re doing with a fitness tracker

- People who are fit through consistent exercise live longer and healthier. They are 50% less likely to get dementia.

- Those who run just once a week (or do something similarly) can reduce the risk of death from any cause by as much as 27%.

- For exercise to make a difference, you need to mix intensity with ease.

- Work on your posterior chain.

Questions? Could be I have some answers… just ask in the Comments section below.

Last Updated on February 25, 2024 by Joe Garma