Longevity Exercise: 7 Anti-aging Interventions Backed By Science, Part 2

Longevity exercise is a descriptive term for any consistently done routine that consists of muscle-building, mobility and cardio exercises. If you could put exercise in a pill, it would be heralded as the miracle anti-aging drug. Exercise is the best thing you can do to improve your longevity, as I will explain.

This guidance on anti-aging interventions is part of an online video course I'm creating about how to age better and live long and strong. If interested, become a Subscriber (it's free) to get my Sunday Newsletter and be notified when the course is available for enrollment.

- muscle/strength,

- mobility, and

- cardiovascular fitness.

As you’ll soon see, if you consistently put some effort into doing these three types of exercise, you reach old age doing back flips, or something like that.

Now mind you, I’m not asserting that exercise will extend your lifespan, like say from 90 to 100; rather, I’m saying — and more importantly, the science shows — that exercise is a powerful promoter of healthspan, not necessarily lifespan.

This begs the question, Why use the term “longevity exercise”?

The answer is that I’m purposely using the word ‘longevity’ to embrace its entomological form:

Note that longevity is not the same as lifespan: Lifespan is how long your live; whereas Longevity distills down to long life with vitality. And that’s what healthspan is as well.

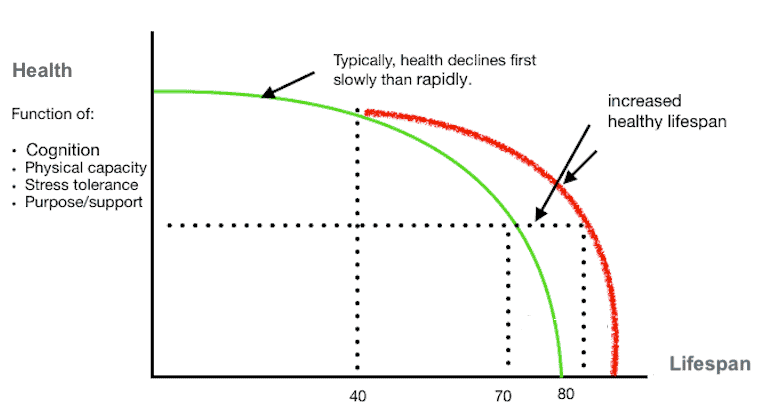

Both longevity and healthspan are aptly depicted by this graph:

If you're not already a Subscriber, go here to learn how to "bend your age curve" and improve longevity.

As you can see, what the graph depicts is a shift in the years lived healthy, which is the primary aim in this three-part series about anti-aging interventions. We want to age without the disabilities of age. We accept growing older chronologically, because that’s unassailable, but we know there’s much we can do to keep ourselves biologically younger.

And thus, I use the historical meaning of longevity — to live a long vital life — to underscore the primary benefit of all the seven anti-aging interventions reviewed in Part 1 (caloric restriction), here in Part 2 (exercise), and in the forthcoming Part 3 (nutracueticals).

Exercise and Longevity

Before we examine the affect that specific types of exercise have on longevity/healthspan, let’s get a sense for how exercise impacts your biology. For that we first turn to some new research published by the medical journal BMJ, and then to two prominent and popular longevity researchers, physician Brad Stanfield, MD and biochemist Eleanor Sheekey.

Motor Activity (Or Lack Thereof) Predicts Risk of Death

Greater longevity is in your grasp, but only if you stand up, reach out and grab it.

New research in August 2021 in the journal BMJ, found that poor motor function among older people can predict a higher risk of death over the next ten years.

Here are the increased odds that someone age 65 who struggles with common activities will die sooner than their peers, other factors being equal:

- 14%: Getting out of a chair

- 15%: Grip strength

- 22%: Walking speed

- 30%: Difficulty with daily activities

Another study published in BMJ found that people with the worst motor function at age 53 are more likely to die during the next 13 years compared with people who had the best motor function. Poor mobility can predict future disease that might otherwise not be evident yet, the researchers concluded, but this they are clear about:

“Relatively low levels of performance in tests of physical capability in mid-life could provide a useful indication of the presence of underlying disease and aging processes that are likely to be detrimental for future health but are not yet necessarily clinically manifest.”

In plain English, what this means is that various tests of physical capacity can determine future health outcomes well before poor health is determined by your doctor.

Two such predictive tests for lifespan are:

- a strong grip, and

- an agile body.

At minimum, you should be able to hang from an overhead bar for at least 15 seconds (grip strength), and be able to get off the floor without climbing up a chair (agility/mobility).

To test how well you’re aging, check out my post, Predict Your Lifespan By These 12 Tests.

Exercise Can Alter Gene Expression

Now let’s get more sciencey to see what’s happening under the hood. At time stamp 4:57 in the video below, biochemist Eleanor Sheekey describes “mechanical transduction” to Dr. Brad Stanfield. This is any of various mechanisms by which cells convert mechanical stimulus into electrochemical activity.

Transduction is an essential regulator of cell biological processes, including cell survival, cell migration, mitosis (cell division), and differentiation (the process during which young, immature (unspecialized) cells take on individual characteristics and reach their mature (specialized) form and function.) [1].

For the sake of clarity, I’ll edit Sheekey’s perspective on the value of exercise as an essential contributor to healthspan extension.

Physical forces, she says, can signal down to the cellular level. When you exercise, you’re stretching muscle fibers, and this translates to stresses and strains on different muscle cells that can affect lipid membranes (flat sheets two molecules thick that form a continuous barrier around all cells), and propagate through different structures within your cytoskeleton that keep your cells intact. That then can signal down into the nuclear membrane and continue the signal on down to transcription factors.

Transcription factors are proteins involved in the process of converting, or transcribing, DNA (a long molecule that contains our unique genetic code) into RNA (a molecule whose primary role is to convert the information stored in DNA into proteins). These transcription factors can alter gene expression (which are turned “on” or “off”)

What this distills down to is that exercise has the ability to alter gene expression, which is unsurprising, because in order for exercise to express physiological and cognitive benefits, it must be able to influence genes.

To watch Eleanor Sheeky’s bit on exercise, go to time stamp 4:57 in the video below. I’ll be talking more about gene expression (aka epigenetics) later.

Strength and Muscle Exercise

The first type of exercises to explore are the type that builds muscle and strength. One of the ways to combat physical age-related concerns — plus maintain range of motion, strength, and balance — is to incorporate consistent strength training into your weekly routine.

As you’ll soon see, if you could do just one type of exercise for longevity gains it would be a combination of exercises that develop muscle and strength.

Muscle/strength training can benefit everyone, but especially older adults by:

- Increasing bone density from the stress put upon bones from the movement and force patterns of strength training, which activate bone-forming cells, making bones stronger and more dense [2].

- Increasing muscle mass, which contributes to more strength, better balance, and an increased metabolism. One study found that by consistently doing a strength training program, older adults were able to improve their muscle mass and muscle strength by 30% [3].

- Enabling better balance and functionality. clearly evident when doing activities such as standing up from a chair, reaching up to get something heavy from a shelf, or tying your shoes — these all require some level of balance, flexibility and strength. Especially for older adults, these benefits translate into a reduced risk of falls or other disabling injuries [4].

- Improving body composition, so important to decrease the chances of obesity, especially as we age (5).

- Improving quality of life, as measured by improvements in their psychosocial well-being, is inevitable for older adults who participate in a regular resistance training routine often see [6].

At this point it should be obvious to you that building muscle and strength is a requirement for improving longevity and overall well being.

Here’s what we’ll cover in this section:

- Build muscle and strength or lose it

- Why strength training is the secret to midlife weight loss

- Math predicts the best way to build muscle

Build Muscle and Strength, or Lose It

Declining strength and loss of muscle are hallmarks of aging.

Current research indicates that the rate of muscle atrophy is nearly 1% per year after age 50, which has an exponential (continually increasing) effect when considered over time [7].

Muscle atrophy is called sarcopenia, the loss of muscle mass and function as we get older. This decrease in muscle mass comes from several factors, including:

- hormonal changes

- increasing inactivity

- an unbalanced diet that’s low in nutritional calories and protein

Sarcopenia is strongly related to falls and overall frailty that can be life-threatening when old, and thereby perhaps the most important reason to do exercises that promote building muscle and strength is to slow down or avoid sarcopenia.

Sarcopenia is a natural part of aging, but it doesn’t have to be; in fact, avoiding sarcopenia is one of the most straight-forward and useful things you can do to slow down the aging process that’s within the span of your control.

So, if you’re wondering what building muscle has to do with promoting longevity, 86 year old sports medicine doctor Gabe Mirkin has your answer:

“Muscles are made up of hundreds of thousands of individual fibers, just as a rope is made up of many strands. Each muscle fiber is innervated [stimulated] by a single motor nerve. With aging, you lose motor nerves, and with each loss of a nerve, you also lose the corresponding muscle fiber that it innervates. For example, the vastus medialis muscle in the front of your thigh contains about 800,000 muscle fibers when you are 20, but by age 60, it probably has only about 250,000 fibers. However, after a muscle fiber loses its primary nerve, other nerves covering other fibers can move over to stimulate that fiber in addition to stimulating their own primary muscle fibers. Lifelong competitive athletes over 50 who train four to five times per week did not lose as many of the nerves that innervate muscles and therefore retained more muscle size and strength with aging than their non-athlete peers.”

Why Strength Training Is the Secret to Midlife Weight Loss

In a study published in June 2021, Iowa State University researchers examined the records of 12,000 mostly middle-aged adults and found that two or more workouts a week were enough to reduce the risk of obesity by 20 to 30% for two decades, including people who do not do aerobic exercise [8].

Bumping it up to an hour or two per week was even better, reducing the risk of obesity by 30 to 40%. Other bonus effects are reduced cholesterol levels, inflammation and blood pressure, as well as a reduced risk of diabetes and heart disease.

Muscle strength has been linked to longer lives, lower risk of obesity, and healthier brain, bones, and cardiovascular systems. It has also been shown to improve self-esteem, boost self-confidence, and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Moreover, resistance training (calisthenics and weight lifting) reshapes our metabolisms and waistlines, reports Gretchen Reynolds, health columnist for the New York Times. She says:

A growing number of studies suggest weight training also reshapes our metabolisms and waistlines. In recent experiments, weight workouts goosed energy expenditure and fat burning for at least 24 hours afterward in young women, overweight men and athletes. Likewise, in a study I covered earlier this month, people who occasionally lifted weights were far less likely to become obese than those who never lifted.

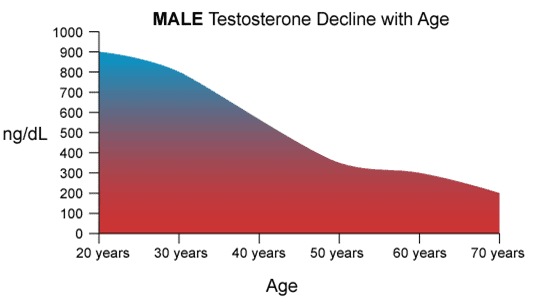

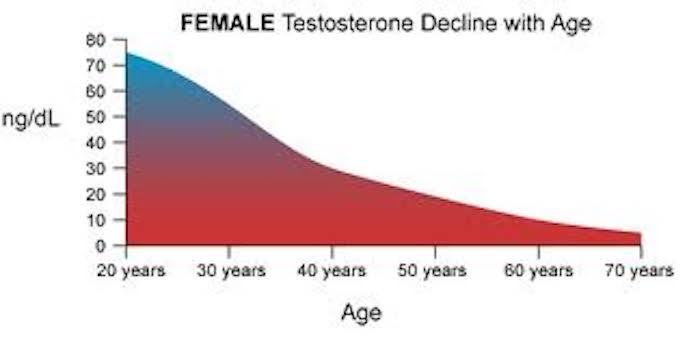

One big reason that resistance training reduces body fat is that it increases testosterone. A Spanish study reports that strength training can increase testosterone by 40%. Given the rapid decline in testosterone that occurs as we age in both men and women, being able to boost it with naturally with strength training should be tired first before trying bioidentical hormone therapy.

Boost Testosterone and Get Lean with 3 Supplements and 3 Techniques

Mathematical Model Predicts Best Way To Build Muscle

The University of Cambridge released the findings of a study recently about the optimum way to build muscle. Again I say, stopping sarcopenia (muscle wasting) from happening as we age is of PARAMOUNT IMPORTANCE if you want to extend your healthspan and keep yourself from tripping on a pebble and breaking your hip.

So, for those of you who take this seriously and therefore do (or want to do) resistance training (weightlifting and/or calisthenics) you’ll be interested in learning that the Cambridge scientists have found the most efficient way to build strength and muscle by dint of a mathematical model:

Lift weights that are 70% of your maximum, one-rep effort.

So, for instance, if you can bench press 100 pounds for one repetition, you’d use 70 pounds and lift it almost as many times as you can, leaving one or two reps in reserve for the second set. Depending on your goals, you would do two to four sets. As applied to push-ups, if you can only do one (your one-rep max), then you could do multiple reps on your knees to approximate a reduction in load to 70% of the one-rep push-up.

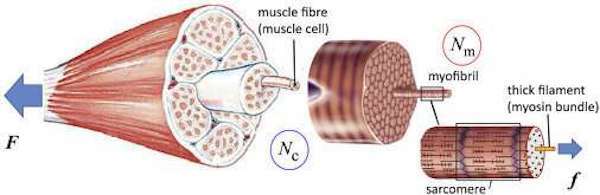

The researchers found this out by examining the ability cells have to sense mechanical cues in their environment, which can be examined by observing how proteins in muscle filaments change under force.

They found that main muscle constituents, actin and myosin (fibrous proteins that stick together) lack binding sites for cell signaling molecules that activates the molecules that generate a chemical signal chain), so it had to be the third-most abundant muscle component called “titin” (another protein) that was responsible for signaling the changes in applied force.

This led to the finding that:

“Our model offers a physiological basis for the idea that muscle growth mainly occurs at 70% of the maximum load, which is the idea behind resistance training,” said Terentjev. “Below that, the opening rate of titin kinase drops precipitously and precludes mechanosensitive signaling from taking place. Above that, rapid exhaustion prevents a good outcome, which our model has quantitatively predicted.”

OK, now that you’ve got those muscles bulging, make sure your joints work.

Mobility Exercise

Mobility is defined as how freely a joint can move through a range of motion. For example — can you bend, then fully extend, your knee under load without any hesitation or pain?

What I mean by “load” is your body weight, at minimum. So, for instance, being able to squat below parallel without restriction or pain is a decent indication of good knee mobility.

Yeah, he’s got some weight on his back, which increasing the load on his knees, but healthy knees can handle that.

Mobility is different than flexibility. Whereas flexibility is the ability of your muscles and other connective tissues to stretch temporarily, mobility involves the articulation joints — in other words, joints in motion.

Mobility is important irrespective of age, but especially so as we get older. Maintaining mobility is key to functioning independently.

According to the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) National Institute on Aging, older adults who lose their mobility (9):

- are less likely to remain living at home

- have higher rates of disease, disability, hospitalization, and death

- have poorer quality of life

Are You Experiencing A Decreased Range of Motion?

Notice that your shoulders, hips, or knees don’t move as well as they used to? As you age, your range of motion — the full movement potential of a joint — decreases due to changes in connective tissue, arthritis, loss of muscle mass, and more.

By how much?

In a study published in the Journal of Aging Research, researchers analyzed shoulder abduction and hip flexion flexibility in adults ages 55 to 86.

They found a decrease in flexibility of the shoulder and hip joints by approximately six degrees per decade across the study participants, but also noted that in generally healthy older adults, the age-related loss of flexibility does not significantly impact daily life [10].

Are You Experiencing Teeter-Tottering Balance?

If your balance isn’t what it used to be, there’s an explanation for that as well.

You maintain your balance using:

- your eyesight

- your vestibular system (structures in the inner ear)

- feedback from joints in the spine, ankles and knees

These systems send signals to your brain to help your body maintain its balance as you move about your day, but as you age these signals aren’t communicated as effectively: Your eyesight gets worse, your cognitive abilities start to decline, and your joints become less mobile. That’s the trend, but you don’t have to comply.

Follow along with this SliverSneakers video to improve your balance and core strength:

For more mobility exercise, check out Part 2 of my six-part series, The Functionally Fast Fit Workout.

The Functionally Fit Fast Workout — Strong, Enduring, Mobile (Part I)

Now that we’ve got your muscles pumping, let’s add the heart to the mix.

Cardiovascular Exercise

The bad news: cardiovascular diseases are strongly associated with aging in humans.

The good news: An increase in aerobic exercise in the elderly is associated with favorable outcomes on blood pressure, lipids, glucose tolerance, bone density, and depression [11].

Exercise training can have a beneficial impact against diseases and metabolic disorders that typically accompany aging, notably cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and osteoporosis [12]. And the opposite occurs for those with a sedentary lifestyle combined with the consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor food, as such lifestyle factors have a compounding, deleterious effect on these disorders [13].

The loss of abdominal fat and reduction in the waist/hip ratio (rather than BMI) help protect against these age-related disorders [14]. But even without weight loss, moderate or even low levels of exercise (e.g. daily 30-min walks) have a positive effect in obese subjects [15] by inhibiting the development of the metabolic syndrome [16].

Develop A Cardio Routine That Suits You

Ideally, your cardio routine will combine aerobics (exercise that elevates the heart at a sustained rate for 20 minutes or more) and anaerobic (spurts of exercise that nearly maximizes the heart rate for two minutes or less).

These are common cardio exercises:

- Walking

- Running

- Bicycling

- Swimming

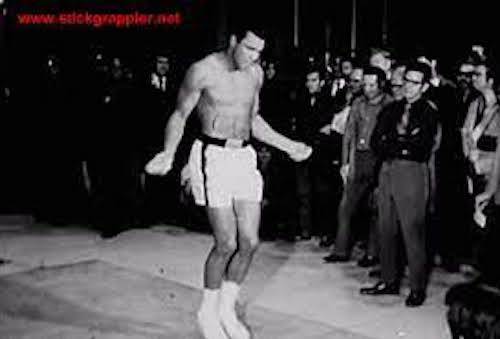

- Jumping rope

All of these cardio exercises can be tweaked to fit your capability and be made to alternate between being aerobic and anaerobic.

For instance:

✔ If you’re unfit, walking can get the heart elevated sufficiently to be aerobic, and you can either walk up stairs or hills to get spurts of anaerobic activity.

✔ Running can be a slow jog for sustain an aerobic period, and then be sped up for anaerobic spurts. The same with bicycling and swimming.

✔ Jumping rope is anaerobic for all but the very fit, as even two minutes will wear out someone who is unfit. But you start with 3o second intervals, 10 seconds rest in between, until you’re skipping around like Muhammad Ali.

Next, let’s turn to how exercise can keep you cognitively healthy as you age.

Exercise and Cognition

I’ve already touched on how the biological effects of exercise could be partly explained through epigenetic mechanisms, and this is also true for neurological/cognitive health.

Recall that epigenetics accounts for how genes might interact with their environment to produce the phenotype. This is to say that genes are influenced by environmental factors (endogenous or exogenous) that are observable in the characteristics of an individual resulting from the interaction of its genotype with the environment [17, 18].

Exercise is a powerful, epigenetic “environmental factor” that influences your phenotype, not only as it relates to how you look and function physically, but also how well your brain works.

Epigenetics plays an essential role in neural reorganization, including those that govern the brain plasticity [19]. (Plasticity refers to the quality of being shaped or molded.)

For example:

- A growing body of evidence indicates that exercise regulates neuroplasticity and memory processes [Ieraci et al., 20].

- Several animal studies reveal how motor activity (exercise) is able to improve cognitive performances acting on epigenetic mechanisms and influencing the expression of those genes involved in neuroplasticity [21].

- Recent evidences demonstrate that exercise can mitigate the harmful effects of traumatic brain injury and aging on cognitive function [22].

All this distills down to the assertion that exercise is not only essential for a healthy aging body, but for a healthy aging brain as well.

And when you combine exercise with some caloric restriction from time to time, good things happen.

Exercise Plus Caloric Restriction

In Part 1 you learned about why various types of caloric restriction (CR) is an important anti-aging intervention. Now let’s quickly integrate that with exercise.

Exercise and CR have distinct molecular signatures [23], and therefore it’s likely that the integration of regular exercise with CR results in synergistic health-promoting effects.

Consider these findings:

- Alternate day fasting combined with exercise is more beneficial for muscle mass than exercise alone [24].

- In non-obese subjects, CR combined with exercise has synergistic effects on insulin sensitivity and the lowering of circulating C-reactive protein, a measure of systemic inflammation [25.

- Scientists think that CR and exercise seem to be mechanistically connected to some extent, since both starvation and exercise induce autophagy, the natural degradation of the cell that removes unnecessary or dysfunctional components [26].

If you currently neither exercise or restrict calories, I recommend that you don’t try to do both at the same time. Instead, choose the one thing you’re most likely to consistently do, and once that’s habitual, add the other.

Choose Your Favorite Intermittent Fasting Protocol (and watch the fat melt away)

Hopefully, you’re now convinced that longevity exercise must be part of your anti-aging regimen, as it’s a formidable and essential “anti-aging intervention backed by science”.

Next up is some inspiration and a few more exercise routines to get you started.

Some Inspiration and Exercise Guidance

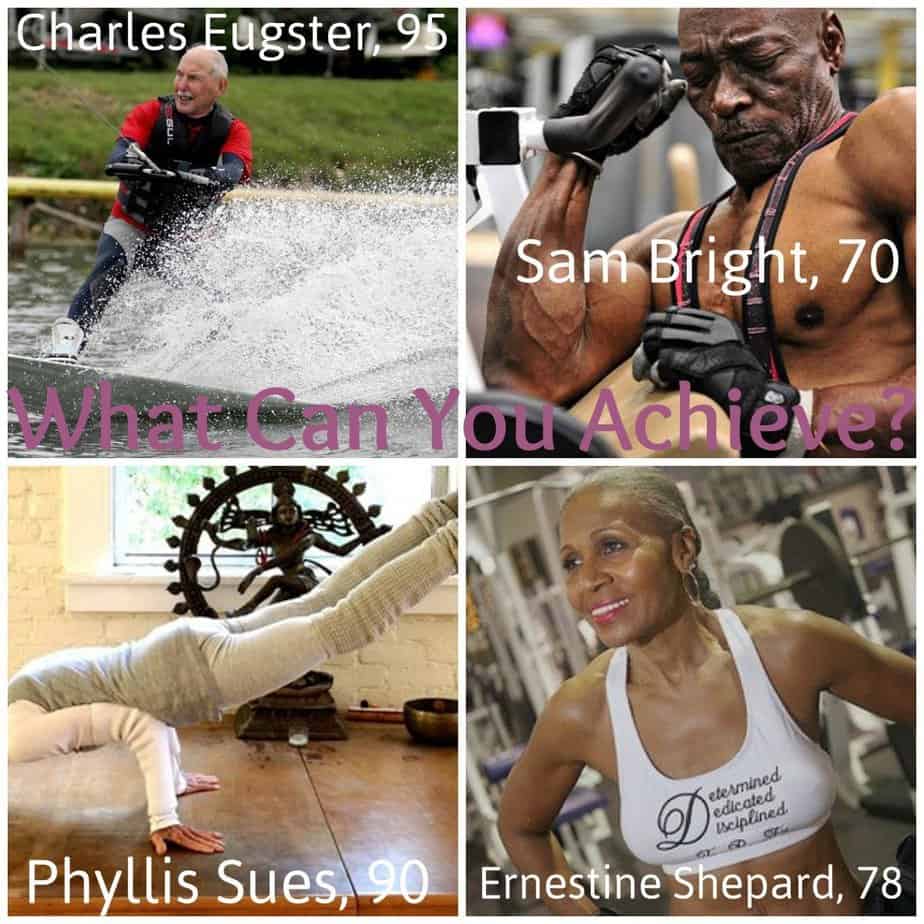

There’s a HUGE difference between the physical capacity of someone who regularly performs resistance exercise (weight lifting and/or calisthenics) and those who do not as they get older:

Those “four masters” look pretty good, yes? More importantly, they function fantastically; well, Charles used to anyway.

Charles Eugster, shown above water skiing at 95, past away in 2017 at the age of 98. He was the poster boy for a long healthspan, as was Jack LaLanne — American fitness and nutrition guru and motivational speaker — because he was still performing his daily exercise routine up until the day before his death at age 96.

If you think you’re too old to start exercising, know that Charles Eugster began exercising at 85. He said, “I looked in the mirror one morning, and I didn’t like what I saw.” He then went on to win more than 100 fitness awards in multiple sports, including bodybuilding and rowing. [27], as well as multiple medals at the World Masters Regatta [28].

Now, I get that Eugster and the other three “masters” referenced above are outliers in that their achievements might be considered extreme, and thereby, unattainable to most of us. That’s just fine, because you only need small doses of resistance exercise to make a difference in warding of sacropenia, as well as to ignite some beneficial epigentically-induced phenotypic changes, if they’re done with some intensity and regularity.

This begs the question, How much exercise is enough to gain longevity benefits?

Answer: I don’t know of any definitive amount, but the more relevant question is, How much exercise are you willing to consistently do?

Like most lifestyle factors, exercise is a personal thing, and thereby must be personalized to fit you. I explore this in the post, Why You Need To Personalize Your Exercise.

What “personalized exercise” means is the exercise that stimulates the most efficient and effective response for you. A recent study involving twins shows that almost everyone responds to the right exercise program, but the right one can differ from person to person. This suggests that personalizing your exercise is a worthwhile endeavor, especially if that means you’ll actually do it on a consistent basis.

7 Functional Fitness Moves Trainers Say Are the Biggest Indicators of Longevity

Whichever longevity exercise regimen you elect to do, try to incorporate the seven functional fitness moves from which you’ll get the biggest bang (results) for the buck (time and effort) .

The term “functional fitness” refers to being capable of physically engaging whatever your environment serves up, such as walking up hills, climbing, lifting things off the ground (like yourself), lifting things overhead, etc.

Such movements can be approximated and enhanced, in terms of their effectiveness, by seven functional compound movements, which you can see demonstrated here.

They include:

- Squats

- Rotation

- Hinge

- Push

- Pull

- Lunge

- Gait

If you want to put together a workout regime for yourself, wade into my six-part series, The Functionally Fast Fit Workout. I’ve also loaded some videos below to get you started.

For most people, the best exercise regimen is a combination of strength and cardio conditioning:

The three exercises above combine cardio and strength training.

With that in mind — combining cardio and strength training — let’s take a look at some options that you may choose from depending on your capacity and interest:

Choose Your Exercise Routine

I’ve showcased three full body routines for you to do.

Choose the one you can do without killing yourself and that you’re willing to do three times per week:

- 7-minute (beginner/intermediate)

- 8-minute (beginner)

- 20-minute (intermediate/advanced)

I’ve marked each of the three according to degree of difficulty, but you can make any routine less or more difficult by:

- Increasing the repetitions

- Increasing the sets

- Doing the routine more than once

First up, the famous, scientifically-proved 7-minute routine.

Have time for another minute?

8 Minute Strength Video for Beginners:

If you like that style of instruction, you’ll find many other exercise routines here.

And for all you over-achievers, next up is a 20-minute full body, no equipment needed, strength and cardio workout that you can watch as you do it.

20 Minute Strength/Cardio Video for Intermediates:

3 Expert-approved Anti-aging Exercise Routines You Can Do and Why You Should Bother

Your Takeaway On Longevity Exercise

Remember these five things about longevity exercise:

- Consistently performing muscle/strength building, mobility and cardiovascular exercise might not make you live longer, but you’ll live longer better.

- You can predict your mortality by a set of tests that test various performance measures, such as grip strength and walking speed — so test yourself if you need some incentive to start working out.

- Exercise works to improve your longevity in many ways, beginning at the epigenetic level (exercise can alter gene expression) as well as reducing or reversing the usual muscle wasting (sarcopenia) that occurs as we age.

- Exercise vastly improves metabolic health, which includes metrics such as body composition, blood sugar, cholesterol, agility and hormone balance (such as increasing testosterone).

- Exercise can keep your mind intact, as it improves neuroplasticity, and thereby cognitive health.

Well, at long last you’ve come to the finish line of this long post. Since you stuck with it this far, it may be presumptuous of me to presume that you got something useful out of this piece on longevity exercises. But if you did, please share it on your social media. Thanks!

Go to Part 3

Last Updated on July 7, 2023 by Joe Garma