Do Longevity Drugs Exist Now? (Yep)

Longevity drugs do exist, as proven by the National Institute of Aging’s Interventions Testing Program. I’ll show you which ones extend lifespan in mice. That has value, because some drugs that benefit mice do find their way to us, so it’s wise to keep up with those critters and the scientists that make them live longer.

Do longevity drugs exist?

I mean, despite all the assertions made by some supplement companies, scientists and biohackers — are there really any longevity drugs that have been proven to extend lifespan in double blind, placebo experiments that have been replicated in various labs?

The fast answer is both “yes” and “no”: Yes in mouse experiments; no in human trials that can stand up to scrutiny.

In this post, I will reveal which drugs have extended the lifespan of mice; drugs that are regularly used by humans, but typically not for life extension, at least not with the approval of the medical establishment.

Why should you care, given that you’re — and I’m guessing here — not a mouse?

You should care because there’s a lot we have in common with mice, genetically and biologically speaking, and sometimes a drug that improves the life of mice, improves ours as well. I encourage you to follow the lifespan studies in mice — some will pave the road for us too.

This post will get you started.

Content

Let’s dig in.

Of Mice and [Wo]Men

Let’s begin with the obvious — it’s problematic to study aging in humans. So, scientists need to study other creatures that pretty much age the same way. Mice fit the bill.

That some longevity drugs have actually increased the lifespan of mice is remarkable, and good news for us, because it may portend what could happen in humans as well. But, unlike with mice, it’s exceedingly difficult to test any intervention on a long-lived species like humans for various reasons, two of which are obvious:

- Humans will not agree to have their lives controlled for several decades by a cabal of scientists; and

- Even if they did, such experiments would be prohibitively expensive.

Rhesus monkeys are much more human-like than mice, and they were the cohort used in two famous experiments that, like many before and after using various other animal cohorts, showed that caloric restriction can increase lifespan in all animals tested. Even so, with a lifespan of about 40 years, Rhesus monkeys are also typically out of bounds to test longevity drugs.

So, long-lived animals are out of bounds. The animals that scientists do want to use to study potential longevity drugs are animals that:

- Have a naturally short lifespan

- Are easy to genetically manipulate, if needed

- Are cheap to buy and maintain

- Reproduce quickly

- Have similar genetic and biological traits to humans

- Don’t have lawyers

Murines fit the bill (mice and rats).

Almost all of the genes in mice share functions with the genes in humans. That means we develop in the same way from egg and sperm, and have the same kinds of organs (heart, brain, lungs, kidneys, etc.), as well as similar circulatory, reproductive, digestive, hormonal and nervous systems. Likewise, mice and humans — as well as many animals — tend to age similarly.

Dr. Richard Miller, who I’ll tell you about in a minute, put it this way in an interview with journalist Arkadi Mazin:

In terms of aging, if I tell you that I have an individual right here in front of me, in my office, that has cataracts, bad hearing, weakened bones, a poor immune system, and a relatively low cardiovascular system, you would immediately recognize that individual as old, be it a mouse, a dog, a horse, or a person. But you wouldn’t know if that’s a seventy-year-old human, or a 25-year-old horse, or a three-year-old mouse.

So, the effects that aging has on mice and on humans are – not in every case, of course, but in most cases – recognizably quite similar. And that’s true for cells that divide, for cells that don’t divide, for structures like the bones and the tendons that are mostly extracellular material. It’s true for complicated circuits, like neuroendocrine feedback circuits, it’s true for cognition.

There are just so many aspects – not all, but so many aspects of aging in humans, mice, dogs, chimps, et cetera that are the same. So, it’s very reasonable to expect that the drug that could block aging effects in all of those tissues in mice might also do very similar things in people.

That Richard Miller knows what he’s talking about is pretty much indisputable.

Of Mice and ITP

In 2002, the National Institute of Aging in the United States began funding the Interventions Testing Program (ITP), a peer-reviewed program designed to identify agents (compounds, molecules and the like) that extend lifespan and healthspan in mice.

Just about any serious person with a good argument for testing some potential longevity drug can petition the ITP to study it. Testing is carried out in the same type of mice at three sites — the Jackson Laboratory, the University of Michigan, and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

To have three different sites is purposeful. The aim is to test if all three sites with different labs and scientists can come up with the same results. If they do, then there’s a higher degree of confidence that the test outcomes are correct.

Testing in the ITP is carried out in two stages:

- Stage I tests a single dose of an agent to determine its effect on lifespan.

- Stage II tests additional doses or alters treatment start times to determine the effects of the agent on lifespan, age-sensitive health measures, and pathology.

Proposed interventions can be pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, dietary supplements, plant extracts, hormones, peptides, amino acids, chelators, redox agents, or other agents, or mixtures of compounds. Priority consideration will be given to interventions that are easily obtainable, reasonably priced, and can be delivered in the diet.

Richard Miller, MD, PhD, mentioned above, heads the ITP. Dr. Miller is highly credentialed: In addition to

his leadership of the ITP, he is a Professor of Pathology at the University of Michigan and directs the Paul Glenn Center for Aging Research.

In an interview with journalist Arkadi Mazin, Dr. Miller acknowledges that many drugs that work in mice do not work in humans, but that it’s “silly” to argue that none would work in humans if tested, he says. He points out that most of the drugs developed for therapeutic effect in people were initially discovered by working on mice and rats, and anticipates that some day soon a drug that will extend life in mice will do so in humans as well.

Longevity Drugs — Peter Attia Interviews Richard Miller

Peter Attia, MD is a physician focused on the applied science of longevity. His practice deals extensively with nutritional interventions, exercise physiology, sleep physiology, emotional and mental health, and pharmacology to increase lifespan (how long you live), while simultaneously improving healthspan (the quality of your life).

Dr. Attia also has an impressively informative podcast, which the following interview with Dr. Richard Miller underscores. (Scroll down to listen.)

At time stamp 1:55:30 Peter and Richard express their bottom line takeaway.

Rich Miller’s basic takeaway:

- Some drugs can expand lifespan by slowing aging

- Some drugs work even when started in middle age

- Some drugs work in one gender, not the other

Peter Attia’s basic takeaway:

- mTOR matters

- Low glucose is better than more

- Sex specific hormones do something positive

Topics discussed with relevant time stamps:

- Dr. Miller’s interest in aging, and how Hayflick’s hypothesis skewed aging research (3:45)

- Dispelling the myth that aging can’t be slowed (15:00)

- The Interventions Testing Program—A scientific framework for testing whether drugs extend lifespan in mice (29:00)

- Testing aspirin in the first ITP cohort (38:45)

- Rapamycin: results from ITP studies, dosing considerations, and what it tells us about early- vs. late-life interventions (44:45)

- Acarbose as a potential longevity agent by virtue of its ability to block peak glucose levels (1:07:15)

- Resveratrol: why it received so much attention as a longevity agent, and the takeaways from the negative results of the ITP study (1:15:45)

- The value in negative findings: ITP studies of green tea extract, methylene blue, curcumin, and more (1:24:15)

- 17α-Estradiol: lifespan effects in male mice, and sex-specific effects of different interventions (1:27:00)

- Testing ursolic acid and hydrogen sulfide: rationale and preliminary results (1:33:15);

- Canagliflozin (an SGLT2 inhibitor): exploring the impressive lifespan results in male mice (1:35:45)

- The failure of metformin: reconciling negative results of the ITP with data in human studies (1:42:30)

- Nicotinamide riboside: insights from the negative results of the ITP study (1:48:45)

- The three most important takeaways from the ITP studies (1:55:30)

- Philosophies on studying the aging process: best model organisms, when to start interventions, which questions to ask, and more (1:59:30)

The interview covers all the longevity drugs that the ITP has tested that exhibited some lifespan extension, and some that showed none. Given that you might not have two hours to spare to listen to the interview, read on.

ITP Longevity Drugs Interventions

Update: Since the original publication of this post, Dr. Brad Stanfield did a video that reviewed the ITP study that showed the combination of rapamycin and acarbose produced the highest percent lifespan extension that has been studied by that organization.

Watch the video, and then read my summary and exposition of the study:

I’ll give you the bottom line summary of longevity drugs that were tested at the ITP that showed lifespan extension. Then I’ll expound a bit about those that can accurately be called “longevity drugs”; well, at least in mice. That said, all of them are being experimented with by people, despite the potential risks.

Tested Longevity Drugs that Worked In Mice

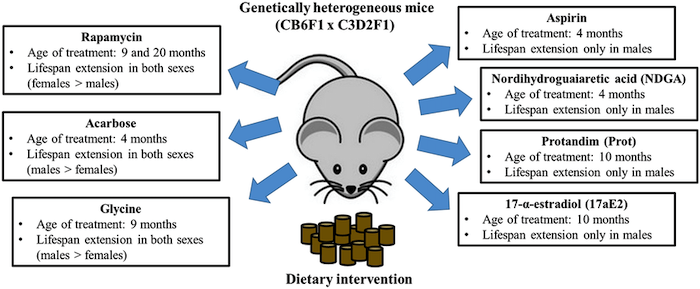

To date, published work has documented major benefits from treatment with:

- Rapamycin,

- Acarbose (males > females),

- Canagliflozin (males only), and

- 17a-estradiol (males only).

Three other agents show smaller, but significant benefits:

- NDGA (nordihydroguaiaretic acid)

- Protandim, and

- Glycine.

Click here to see the full list of drugs that did and did not extend lifespan in ITP mice tests.

Unsurprisingly, most of these proven longevity drugs (in mice) have to do with metabolism and cellular nutrient signaling. The reason this is not surprising is because caloric restriction, which works via nutrient sensing, has been repeatedly shown to be the gold standard in prolonging lifespan and healthspan in all animal models tested, from worms and flies up the evolutionary scale to Rhesus monkeys.

Let’s touch on each of these proven longevity drugs with documented major benefits.

Rapamycin

Rapamycin is a potent antitumor and immunosuppressive drug used in clinical settings to prevent rejection in organ transplantation and to treat certain types of cancer. In much smaller doses relative to animal size, rapamycin has proven to extend lifespan in every animal model it’s been tested in, from yeast, worms, flies, rodents [1], and now in dogs [2].

As you might expect, some people are throwing caution to the wind and are experimenting with rapamycin. A prescription is required, and some doctors who are familiar with using the drug for lifespan purposes write them.

Rapamycin increases the median lifespan in mice equally, whether started on the drug at nine or 20 months of age. As as you’ll soon learn, two others are effective when administered late in life as well.

I’m intrigued by rapamycin and am following developments in this drug very closely. The Rapamycin News website keeps up to date on the drug.

If you’d like to learn more about how rapamycin works through the nutrient sensing paradigm, read my post, Do These 2 Anti-aging Pills Really Work.

Acarbose

Acarbose is a common anti-diabetes therapy; more so in Asia than the U.S. where metformin is more popular. They are similar drugs, but have some different effects.

A 2016 study showed that after 48 weeks, triglyceride and 2 hour post-challenge plasma glucose levels in patients taking acarbose were lower than those taking metformin; whereas fasting plasma glucose was higher in patients taking acarbose than those taking metformin.

Such differences may seem insignificant and may or may not explain why acarbose proved to be an effective longevity drug for mice while metformin was not.

Mice that began taking acarbose in midlife experienced half the longevity effect.

Rapamycin and Acarbose

Rapamycin works very well in male and female mice, while acarbose works significantly in both sexes, but has a much stronger effect in males.

In males, the combination of rapamycin and acarbose together is superior than either by themselves: the combination gives male survival a 34% boost (the largest percentage increase seen in male or female mice studied at the ITP) and produced a 28% increase in median lifespan in females.

When you give acarbose and rapamycin together to females, they don’t do any better or any worse than on rapamycin alone. This is not too surprising because acarbose renders only a small effect in females. That said, the combination is the best thing the ITP has studied for any sex, although it is male specific.

(Note: A recently published study (May 2022) tested phenylbutyrate along with rapamycin and acarbose in mice and found “… that a combination of three drugs previously shown to enhance lifespan and health span in mice is able to delay aging phenotypes more effectively and more robustly than any individual drug in the cocktail when started at middle age and given for a short period of time.” Phenylbutyrate is used to treat urea cycle disorders.)

Canagliflozin

Like metformin and acarbose, canagliflozin is a drug medication used to treat type 2 diabetes. It is a third-line medication to be tried after metformin, often a first-line medication for type 2 diabetes.

Canagliflozin doesn’t prevent glucose absorption, but it prevents very rapid increases in blood glucose levels after ingesting low fiber carbohydrates.

Male mice given canagliflozin experienced up to a 14% increase in median lifespan, and delays various chronic diseases as well [3].

17α-estradiol

17-α estradiol is a weak estrogen and a potent 5-α reductase inhibitor that has been shown to improve metabolic function, enhance insulin sensitivity, and reduce fat and inflammation in old male mice without causing feminization [4,5]. (5-α reductase inhibitors are drugs that are used in the treatment of an enlarged prostate gland (benign prostatic hyperplasia) and male pattern hair loss. Drugs in this class are finasteride and dutasteride.)

Initially, scientists who studied 17α-estradiol were surprised that it worked to extend lifespan even if started late in a mouse’s life — the protocol started in early middle aged mice (16 months) worked as well as for young mice aged nine months of age.

Clearly, Aging Can Be Slowed

The data is now overwhelming that aging can be slowed, and that is done by extending healthy lifespan (healthspan). The drugs that the ITP have tested to be pro-longevity keep mice healthy longer, and that’s why they stay alive longer.

As presented at the Miller lab’s website, demonstration that drugs can slow aging and extend healthy lifespan in mammals have four key implications:

- It refutes the idea that aging is too complex to be altered by simple interventions.

- It provides clues about the cellular and physiological pathways that modulate the aging rate and multiple disease risks in mammals.

- It provides new tools – in addition to dietary restriction and single gene mutants – for testing ideas about the biology of aging.

- It provides motivation and guidance for future development of anti-aging drugs that might work in people.

During the aforementioned interview conducted by Arkadi Mazin, Dr. Miller made several points about how longevity science is changing for the better.

One distinction that resonated with me is that these days researchers focus on drug target discovery. They observe what the drug is doing and then analyze if that be a mechanism that promotes or slows aging. Sometimes, he says, scientists don’t know the target. For rapamycin, the target famously is an enzyme called TOR, the Target Of Rapamycin or mTOR (mechanisitic Target of Rapamycin), but what’s unknown is whether the anti-aging effects of rapamycin are accomplished by a change in the pineal gland in the brain, in the brown fat, in the white fat, in the liver, or in the arteries.

In the case of acarbose and canagliflozin, many aspects of aging are slowed (at least in males) by preventing daily surges in glucose. That’s an opening, a clue, because researchers will want find out why. Why is it that the daily surges and glucose are a key element in males for timing the aging process? And so scientific inquiry is launched.

Why the gender difference?

It’s unclear why these longevity drugs have a gender bias. What is observed is that this bias is not ubiquitous, even in drugs that preferentially benefit lifespans of male mice. For instance, although males given 17α-estradiol or acarbose gain improvements in functions such as balance and grip, strength, and endurance on a rotating rod, there are a few such functions that are improved in female mice as well, although they were not identified.

Your Takeaway

Science is quickly advancing along a path that will someday deliver drugs that will slow down the rate you age. But don’t passively wait for them. There are things you can do now that appreciably extend your healthspan, and the top two are not mysterious:

Exercise consistently and eat like a Blue Zoner.

That said, remember these four things:

- Certain drugs have been proven to improve the longevity and healthspan in mice, and they tend to work via cellular nutrient signalling. Another way of thinking about that is how these drugs influence metabolism.

- Mice are not humans; there are important differences. But many drugs benefical to mice make their way to humans, and so might some of those that have been shown the the Interventions Testing Program to extend the lifespan/healthspan of mice.

- Because of #2, it makes sense to follow up on how the drugs that are effective on extending lifespan in mice are moving up the animal chain. For instance, rapamycin is now being studied in dogs.

- Humans are experimenting with all of the drugs shown to effectively extend mice lifespan, but this can be dangerous unless you are being frequently examined by a doctor who is very familiar with such drugs.

Last Updated on October 8, 2022 by Joe Garma