No Benefit to Time-restricted Eating?

There’s no benefit to time-restricted eating, two recent human trails conclude, as opposed to regular caloric restriction if calories consumed are the same. This conclusion pushes back on many animal studies that assert the opposite. What’s true? Should you try TRE to lose weight and gain health?

If there’s no benefit to time-restricted eating, many of us will be sorely disappointed, given that No Benefit time-restricted eating (TRE) has become very popular over the past several years. Often referred to as Intermittent Fasting, TRE is simply the practice of shortening the window within which you eat, as opposed to eating whenever you want to, which pretty much means all day long and into the night.

If there’s no benefit to time-restricted eating, many of us will be sorely disappointed, given that No Benefit time-restricted eating (TRE) has become very popular over the past several years. Often referred to as Intermittent Fasting, TRE is simply the practice of shortening the window within which you eat, as opposed to eating whenever you want to, which pretty much means all day long and into the night.

TRE has been studied in several animal cohorts, from flies to monkeys, and the evidence has established the point of view that it helps reduce body weight and improve various metabolic markers, such as blood lipids, glucose, insulin and various cardiometabolic factors.

But now two recently published human studies are casting a long shadow over commonly accepted health benefits attributed to TRE, and a controversy is brewing. In this post, I will describe TRE, review the two studies, indicate where they may not be as convincing as some think, and report on the push-back by TRE advocates.

This can be a confusing topic, given that some of the scientists who study TRE disagree about what, if any, health benefits can accrue to humans who practice TRE versus those who do not, assuming an equal amount of calories consumed.

In this post, I dig into the controversy and render my opinions.

Post content:

What Is Time-restricted Eating?

Before we get into the two studies, let’s let Dr. Satchidananda Panda set the stage for us. He’s the right person to expound on the topic of TRE for several reasons, one of which is that his lab coined the term, Time-restricted Eating, and the other is that, based on his research, he coined the phrase:

When you eat is more important than what you eat.

Dr. Panda is the Professor of Regulatory Biology Laboratory a the Salk Institute where he studies the genes, molecules and cells that keep the whole body on the same circadian clock. He and his colleagues assert that confining caloric consumption to an 8 to 12 hour period –- as people routinely did just a century ago -– might stave off high cholesterol, diabetes and obesity.

In the following nine minute clip, Dr. Panda explains the rationale behind the metabolic benefits associated with time-restricted eating in an interview with Dr. Rhonda Patrck, where he says:- TRE does not explicitly involve reducing calories, but rather is an eating pattern wherein a person confines the time of day that they eat to a limited window and fasts for the remainder of the day.

- Preclinical data indicate that feeding animals in a restricted window has beneficial effects on metabolic health – even in overweight animals eating a poor diet.

- Consuming, digesting, and metabolizing food generates reactive molecules that can damage cellular components, including DNA. Fundamental to the benefits associated with time-restricted eating is the concept of allowing the body time apart from eating to rest, repair and rejuvenate itself.

Click here to watch the entire interview

Now that you’ve got a good idea about what TRE is about, and the purported health benefits attributed to it, it’s time to get to the recent controversy that presents an alternative view.

There’s No Benefit to Time-restricted Eating, Say Two Studies

A study called Calorie Restriction with or without Time-Restricted Eating in Weight Loss was just published on April 21, 2020 in the The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). It has ignited a storm of controversy. I’ll address that soon, but I want to begin with another study called Effects of Time-Restricted Eating on Weight Loss and Other Metabolic Parameters in Women and Men With Overweight and Obesity, published in the JAMA Internal Medicine (JAMA) journal in 2020. This older study sets the stage, so I’ll begin with that one.

The JAMA-reported study

The aim of this study was to examine the effect of TRE on weight loss and metabolic health in 105 overweight and obese adults (the number who completed the study) in the USA, evaluated over a 12 week period and divided into two groups:

- The Consistent Meal Timing (CMT) group and was instructed to eat three meals a day at set intervals, with snacks permitted if they got hungry.

- The Time-restricted Eating (TRE) group and was instructed to eat whatever they wanted between noon and 8 p.m. and nothing except water, tea or coffee, without amendments (milk, sweeteners, etc.), during the intervening 16 hours, including sleep time.

Calories consumed, macronutrient proportions (protein, fat and carbohydrates) and physical activity were not controlled in either group. This was because the researchers wanted to determine if when participants ate (in this case during an 8 hour window) made a difference in weight loss (as well as in other health metrics, such as blood lipids, glucose, insulin and cardiometabolic markers) as opposed to calories consumed during the day.

Study Results and Conclusions

Participants lost a small amount of weight — an average of two pounds in the time-restricted eating group, and 1.5 pounds in the control group, a difference that was not statistically significant, which was also true of the relative differences between the the participant’s metabolic markers.

The researchers concluded that TRE did not result in weight loss when compared with a control prescription of three meals per day. Time-restricted eating did not change any relevant metabolic markers.

Oddly, there was a decrease in Appendicular lean mass (ALM) in the TRE group compared with CMT, and Oura ring data revealed significant changes in sleep efficiency, sleep latency, and awake time in the TRE group and between groups. (ALM is the sum of the lean tissue in the arms and legs, and the Oura ring tracks various biomarkers, such as sleep.) I’ll address both of these unexpected results in a moment. both of which I will address in a moment.

Together, the results of this study, say the researchers:

- Do not support the efficacy of TRE for weight loss;

- Highlight the importance of control interventions; and

- Offer caution about the potential effects of TRE on ALM.

As just mentioned, this study had two result that surprised the scientists conducting it:

- The TRE group lost lean muscle mass than the CMT group; and

- The TRE group slept better.

Losing lean muscle is not a good thing, particularly as you get older, as this can lead to sarcopenia (muscle wasting), a common problem among the elderly, and a condition that can lead to compromised physical function and an increased incidence of falling.

The effect of TRE on lean mass is largely unexplored. That said, the researchers made these observations:

- Prior studies show that TRE prevents gains in lean mass.

- Ad libitum feeding (eat when and how much you want) during TRE leads to reduced calorie intake and might also reduce protein intake.

- These data highlight the importance of adequate protein consumption while adhering to a TRE diet. Many studies have shown that adequate/excessive protein consumption during weight loss can mitigate losses in lean mass.

- The loss of ALM during TRE could be mitigated by increasing the number of meals within the eating window or consuming protein supplements.

- Timing of protein consumption may also play a role in changes in lean mass.

The researchers had no explanation for the better sleep quality among those in the TRE group.

My 2 Cents

Being a TRE advocate and practitioner, I was a bit surprised by the findings of this study. Extensive research by scientists who study the effect of circadian rhythms on food metabolism, among other things, clearly show health benefits associated with eating when you’re most metabolically active, which for diurnal animals, like humans, is during the day.

Given this perspective, it’s unsurprising that Dr. Panda has pushed back against the next study I’m about to tell you about that largely confirmed this one, but first I want to address muscle loss and sleep quality.

Regarding the greater loss of lean muscle in the TRE group, I agree with the researchers that if you’re going to eat fewer meals and/or in a narrower than usual time frame, there may be less opportunity, or less inclination to ensure enough ingested protein to counter muscle attrition. Personally, I have not experienced this during my several years of consistent TRE practice.

Regarding better sleep quality for the TRE group, it’s generally true that eating an hour or less before bed can be detrimental to sleep quality; therefore, it makes sense that those in the CMT group who ate close to bed would experience worse sleep quality than those in the TRE group who stopped eating by 8:00 pm.

The NEJM-reported study

Like the one just covered published in JAMA, the study just published in the study just published in NEJM examined weight loss and the health effects of TRE, but there was one significant difference between the two studies — JAMA did not restrict calories, whereas NEJUM did.

But, as in JAMA, NEJM concluded that there was little difference in weight loss or health benefits between the two groups, which I found odd, for as you’ll soon see, there were differences that many people would judge significant.

This one-plus minute video summarizes the NEJM study:

Unfortunately, it appears there is only a paid access to the full study, but given its excellent review, it appears that MedPage Today was able to read it all. I’ll summarize what it reported.

Like the JAMA published study, this one posits that the long-term efficacy and safety of time-restricted eating for weight loss are not clear, and so the researchers randomly assigned 139 patients in China with obesity to:

- Group 1 — Time-restricted eating (eating only between 8:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m.) with calorie restriction.

- Group 2 — Eat any time up to 7:30 p.m. with calorie restriction.

- Calories for men — 1500 to 1800 per day for both groups.

- Calories for women — 1200 to 1500 per day for both groups.

So, the first difference between this study and JAMA is that both groups were calorically restricted. But both studies wanted to see if there was a difference between weight loss and so-called “secondary outcomes”, such as changes in waist circumference, body-mass index (BMI), amount of body fat, and measures of metabolic risk factors.

Study Results and Conclusions

During the 12-month study, both groups lost a significant amount of weight from baseline:

- Time/calorie-restricted diet: 8.0 kg weight loss

- Calorie-restricted diet alone: 6.3 kg weight loss

Yes, the TRE group lost more weight, but it wasn’t deemed statistically significant. Nor was there significant differences in other metabolic outcomes at 6 and 12 months, such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and lean and fat mass, among others — as both diets led to significant improvements from baseline.

Irrespective of statistical significance, the differences showed improvements in the TRE group. At 12 months, for example, these clinical measures were:

- BMI: -2.9 for time/calorie-restricted vs -2.3 for calorie-restricted

- Waist circumference: -8.8 cm vs -7.0 cm

- Body fat mass: -5.9 kg vs -4.5 kg

- Body lean mass: -1.7 kg vs -1.4 kg

- Body fat percentage: -4.3% vs -3.0%

- Area of abdominal visceral fat: -26.0 cm2 vs -21.1 cm2

- Area of abdominal subcutaneous fat: -53.2 cm2 vs -37.0 cm2

Both groups’ cardiovascular risk factors (which included blood pressure, pulse, triglycerides, cholesterol, glucose, insulin resistance, and others) showed significant improvements from baseline due to the caloric restriction, not the time window within which the eating occurred; however, most measures except for pulse, LDL cholesterol, and 2-hour postprandial glucose levels favored the time-restricted eating group.

So, all-in-all, you could reasonably conclude that the TRE group fared better than the Calorie Restricted group, but that didn’t stop the many reviews of this study with headlines such as Year-long study shows time restricted diets offer no benefit, or Scientists Find No Benefit to Time-Restricted Eating.

Drs. Panda, Laferrère and Stanfield Push Back

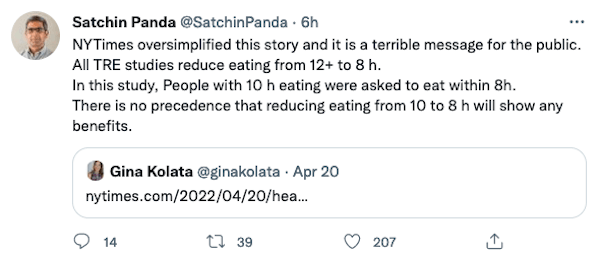

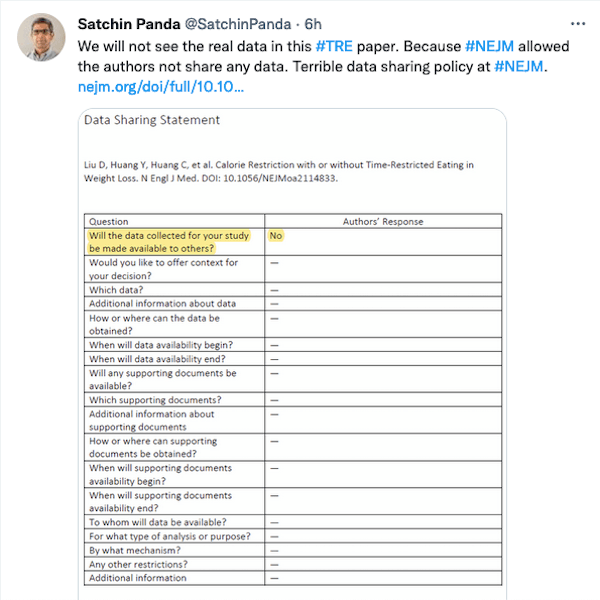

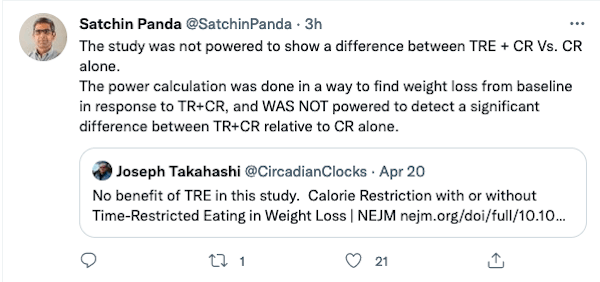

Unsurprisingly, apparently defensive of his life’s work, Dr. Panda has pushed back. Note these screenshots I took of a few of his Twitter posts:

If those Twitter posts are too cryptic, know that Dr. Panda joined forces with Blandine Laferrère, MD, PhD, of the Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City to write an accompanying editorial in response to the NJEM study, calling the baseline window of eating “relatively short”, suggesting that the time-restricted intervention only cut this window by roughly two hours might be the reason why not many differences were seen:

Persons whose habitual time period for eating is long are likely to benefit the most from time-restricted eating… the reduced caloric intake may have blunted any effect of time-restricted eating independent of calorie restriction.

Moreover, Panda and Laferrère remarked that this group of participants was generally healthy at baseline, which may have “left little room to test whether time-restricted eating plus calorie restriction has a significantly greater effect on cardiometabolic risks than calorie restriction alone, as has been observed in studies that involved patients with metabolic syndrome.”

The pair made these two suggestions for future research on the topic:

- Delve deeper into the specifics of time-restricted eating, including finding the best window time-frame for time-restricted eating — including if there’s a difference of an early-in-the-day versus late-in-the-day window.

- Determine who would most benefit from a TRE strategy.

Finally, on the dissenters side of the equation, let’s watch what Dr. Brad Stanfield analyze the NJEM-reported study. Unlike Drs. Panda and Laferrère who are PhDs, Dr. Stanfield is an MD who routinely analyzes longevity studies on his YouTube channel.

Stanfield’s conclusions about the study boils down to this:

- At 139 total (both groups), the sample size (number of people studied) was too small.

- The difference in weight loss between the two groups (1.8 kgs/4 pounds) did not meet statistical significance because the bar was set too high at 2.5 kgs/5.5 pounds of weight loss; in effect, any amount under that did not count.

- The three-hour time differential between the groups (4:30 p.m. vs 7:30 p.m.) is not substantial enough to obtain significant weight loss and other beneficial health outcomes.

Watch Dr. Stanfield’s review:

My 2 Cents

My extensive reading about TRE and circadian rhythms leads me to support Dr. Stanfield’s perspective about the time differential between the two groups as being too close to enable substantive weight loss and health benefits for the TRE group with a feeding window that ended at 4:30, versus the other group that ended its feeding window at 7:30.

However, I think it’s not the three hour difference that makes the difference, but the fact that the time unrestricted group stopped eating at 7:30 p.m, which is relatively early as compared to what most of us do as we nibble away throughout the night. I suspect that given the diurnal circadian and metabolic patterns of humans, eating later that 7:30 in the evening would have negative health and body weight impacts that would be more substantial, and that this scenario more befits most people’s common practice, which is to eat well after 7:30 at night.

I’ll add the rest of my “2 cents” on this study along with the rest of my conclusions below.

No Benefit to Time-restricted Eating? My Conclusions

The beauty of the scientific method is that it proposes a hypothesis, tests its validity and then welcomes the scientific world to try to replicate results. This is now being done in human trials, and it appears that there’s a lot of nuance.

I think you can expect to see more human studies on TRE, which may or may not confirm the conclusions of the two covered in this post. I’d say the net of the two studies covered here at slightly gives the nod in favor of TRE, given the modest, but directionally positive results of the second, longer study.

What it all boils down to is: Would TRE be beneficial to you?

Fast answer: It wouldn’t hurt to try (assuming you’re not ill).

Slow answer: Eat less, more plants, stop eating two or more hours before bed, ensure you get enough protein in every meal, and let more of that be plant protein (soy, lentils, beans).

As mentioned, I’ve been practicing TRE for years now. I have no idea if it’s made me more healthy, because I don’t have a control; meaning, I didn’t cut myself in half and have Joe1 eat whenever and Joe2 do TRE.

With TRE, I’m about the same weight, test out with the same metabolic markers year in, year out, still have muscle, still can push some weight — no sacropenia here.

But I don’t just eat anything. I pretty much have a Mediterranean Diet, but no meat, just fish. I do supplement with whey and pea protein — a pea protein powder shake if my meal doesn’t have enough protein, and a whey protein powder shake after weight lifting, as it provides the best protein muscle synthesis.

The biggest reason I do TRE is to give my body a digestion break, not to lose weight. A break from digestion allows cellular repair, although a 16-hour period of no eating that occurs during a noon to 8:00 pm TRE period isn’t long enough for autophagy to kick in. The data is not clear on this, but it appears that you need to fast for longer than a day for autophagy to happen, which is really when the cellular repair that’s thought to prolong healthspan begins to become meaningful. (Read my post, How to Stimulate Autophagy to Dramatically Improve Your Health.)

The bottom line: If you try TRE, ease into it gradually, eat real food, make sure you get enough protein, stop eating before you’re full, and stop eating and drinking two or more hours before bed.

If you have questions about any of this, ask away in the Comments below.

Last Updated on April 11, 2023 by Joe Garma