When You Eat Is More Important Than What You Eat, Says Dr. Panda

One of the foremost experts on circadian rhythms says that “when you eat is more important than what you eat”. Don’t eat at night, lose body fat and get healthier.

Credit: http://www.womansday.com/health-fitness/nutrition/news/a51006/when-you-eat-may-be-more-important-than-what-you-eat/

We now know that not only what and how much we eat, but WHEN WE EAT makes all the difference in the world to our vitality and health, particularly as we age. In fact, when you eat is more important than what you eat.

And thus…

What you need to get from this article is:

Stop eating as early as you can in the evening; 7:00 PM is good.

Let’s dig in to find out why…

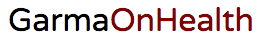

Your Circadian Rhythm Directly Impacts Your Health

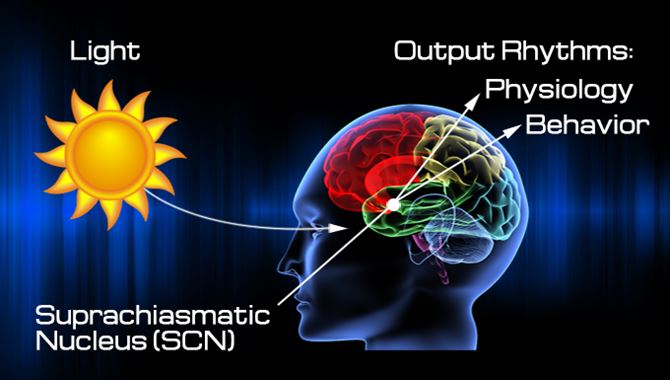

Circadian rhythms – our so-called “circadian clock” — run a 24-hour internal clock that’s ticking in the background of our brain and cycles between sleepiness and alertness at regular intervals. It’s also known as the sleep/wake cycle.

For most adults, the biggest dip in energy happens in the middle of the night (somewhere between 2:00am and 4:00am, when they’re usually fast asleep) and just after lunchtime (around 1:00pm to 3:00pm, when they tend to crave a post-lunch nap).

A part of your hypothalamus (a portion of your brain) controls your circadian rhythm rhythm, but outside  (exogenous) factors like lightness and darkness can also impact it.

(exogenous) factors like lightness and darkness can also impact it.

When it’s dark at night, your eyes send a signal to the hypothalamus that it’s time to feel tired. The brain then sends a signal to the body to release the hormone melatonin, which makes your body tired.

That’s why your circadian rhythm tends to coincide with the cycle of daytime and nighttime (and why it’s so hard for shift workers to sleep during the day and stay awake at night). (1)

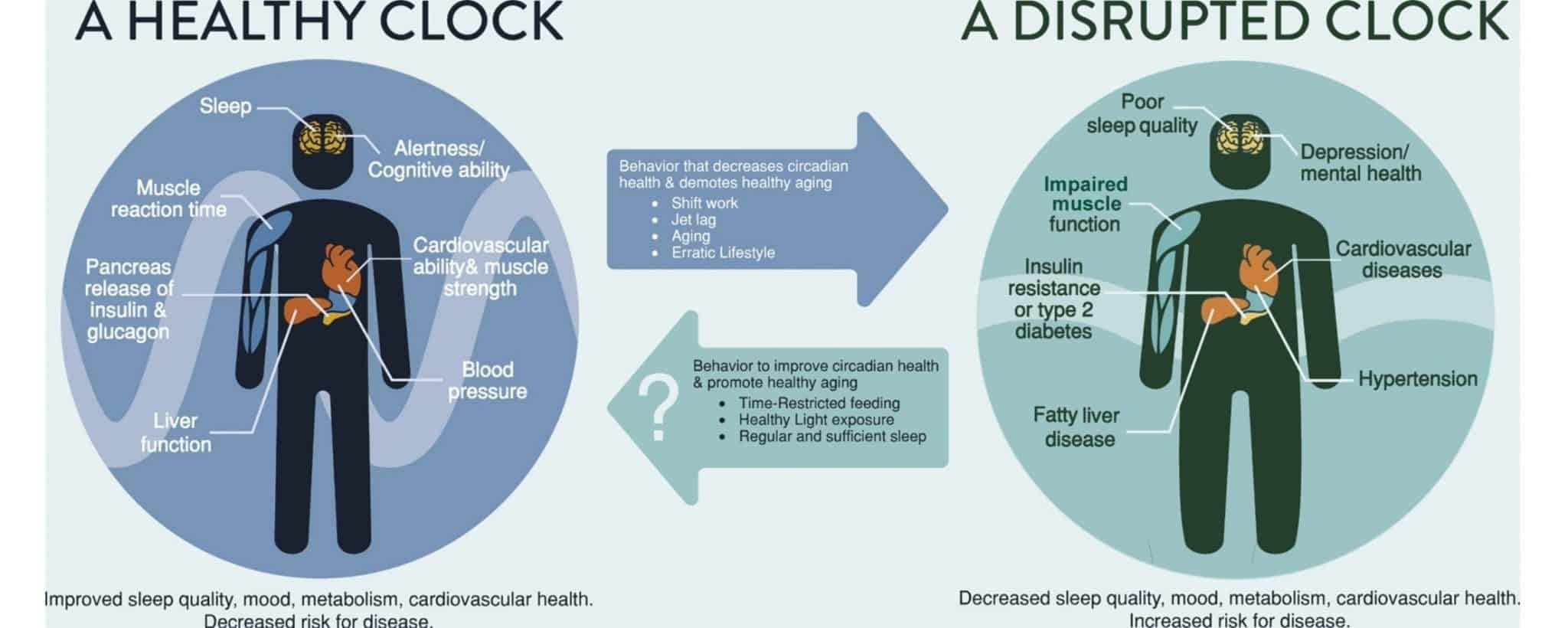

A summary of the science research paper published on Science Direct entitled Circadian rhythms, time-restricted feeding, and healthy aging provides us a concise, current understanding of the profound effect that our circadian clock has upon metabolism and physiology; to wit:

- Circadian rhythms optimize physiology and health by temporally coordinating your cellular function, tissue function and behavior.

- Feeding-fasting patterns are external cues that profoundly influence the robustness of daily biological rhythms.

- Erratic eating patterns can disrupt the temporal coordination of metabolism and physiology leading to chronic diseases that are also characteristic of aging; however, sustaining a robust feeding-fasting cycle, even without altering nutrition quality or quantity, can prevent or reverse these chronic diseases.

- In humans, epidemiological studies have shown erratic eating patterns increase the risk of disease, whereas sustained feeding-fasting cycles, or prolonged overnight fasting, is correlated with protection from breast cancer.

The research paper’s summary concludes with this:

“Therefore, optimizing the timing of external cues with defined eating patterns can sustain a robust circadian clock, which may prevent disease and improve prognosis”. (2)

Which simply means this:

When you eat (and when you don’t) is more important to your health than what and how much you eat!

Enter, stage right, Dr. Satchin Panda

Dr. Panda: “When you eat is more important than what you eat”

Dr. Satchidananda Panda is the Professor of Regulatory Biology Laboratory a the Salk Institute where he studies the genes, molecules and cells that keep the whole body on the same circadian clock.

He and his colleagues have made these three remarkable discoveries:

- That confining caloric consumption to an 8- to 12-hour period –- as people did just a century ago -– might stave off high cholesterol, diabetes and obesity. He is exploring whether the benefits of time-restricted eating apply to humans as well as mice.

- That a single gene that can simultaneously reset all the cells in the SCN*. Mice with the lowest levels of the gene recovered the fastest from a simulated time zone change. The finding suggests a new target for treating jet lag or sleep disorders.

- That a pair of genes help keep eating schedules in sync with daily sleep cycles, making you feel hungry for meals at the same time every day. Mutations in these genes could explain night eating syndrome.

If you’ve quickly scanned the above mentioned three discoveries made by Dr. Panda, I encourage you to go back and read them slowly, as they will have a profound impact on your health (and possibly girth) should you decide to abide by them.

What Dr. Panda has pretty much proven (and I say “pretty much” only because definitive conclusions in humans are still forthcoming) is that:

You can prevent some of the most pernicious age-related chronic diseases by simply confining all your eating to an 8-to-12 hour “feeding window” that ends (as we’ll soon see) by 7:00 PM.

Humans, take note of a TED Talk about mice

I hope that your appetite is whet enough to watch the following Dr. Satchidananda Panda TED talk.

Here’s a snap shot of what you’ll discover, followed by Dr. Panda’s presentation. (Scroll down if you prefer to watch rather than read.)

Circadian clocks are present in different parts of our body. They turn on and off thousands of genes at different times of the day, and by doing so they tune our physiology, metabolism and other biological functions to specific times of the day.

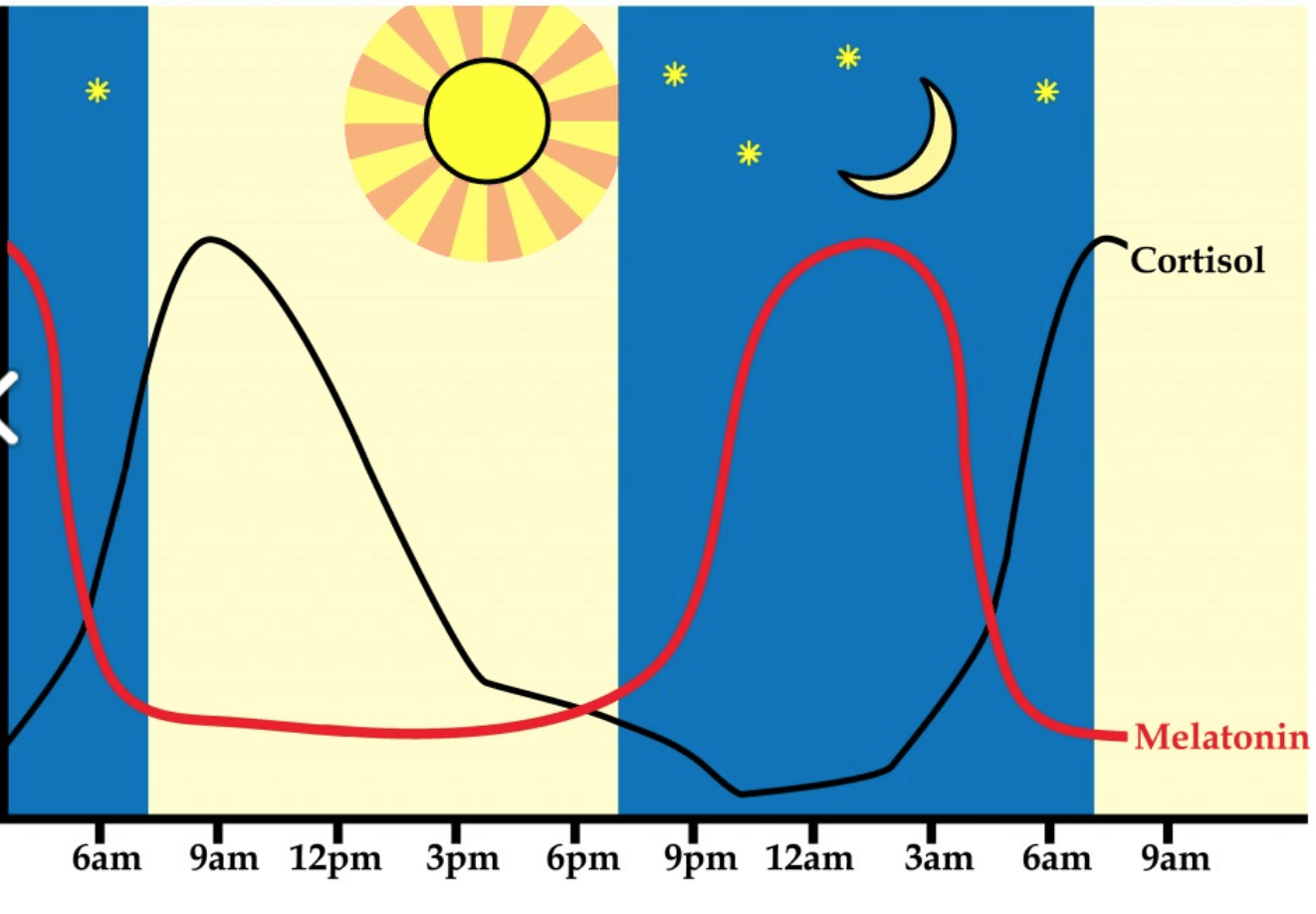

For example, at 2:00 in the morning the typical person is experiencing his or her deepest sleep. Over the next few hours, our internal clock prepares us to awaken by warming up the body, increasing the heart rate, reducing the melatonin level and increasing the stress hormone, cortisol, as well as increasing digestive juices and the hormones that assist in food digestion.

By the time we begin our day and school or work, our brain is at its peak performance capacity, and that point is ideally honed to solve complex analytical problems and make important decisions.

Come mid-afternoon, the clocks in our muscles, sorta speck, fine-tune muscle tone and improve motor control, making that time the ideal time to workout.

As the sun sets, our inner clock prepares us to sleep by dropping our core body temperature, increasing melatonin and decreasing cortisol.

All this happens automatically, but not without a reset.

We have to reset our circadian clock, as it must be adjusted and tuned to the light/dark cycle of the environment you’re in, otherwise you wouldn’t be able to get over jet lag. It’s therefore very useful to understand how our environment tunes our clock so that we may exert better controls over our circadian rhythm and, thereby, our overall health.

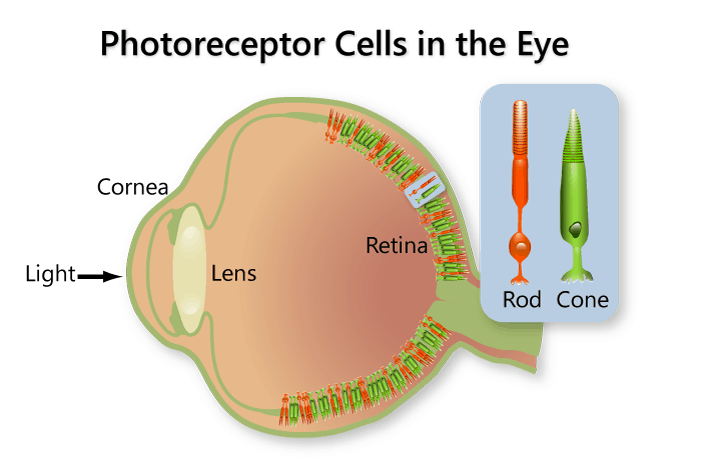

For instance, we know that light resets the inner clock, not sight. Blindness informs us about this. If a blind person without a functional rod and cone is put in a room filled with bright light for a few hours in the middle of the night, his or her inner clock and sleep/wake cycle will be altered.

If you place various frog species in bright sunlight their skin color will change. In their case there’s a light sensor in the skin that’s also present in human eyes. In our case, there are about 5,000 blue light sensors that send the blue light prevalent in our surroundings to different parts of the brain.

When we open our eyes in the morning, this melanopsin (a type of photopigment) blue light sensors perceives light and tunes our internal clock to the local time. Then throughout the day it senses light, helps make us alert, even happy, and can suppress sleep in the evening after sundown should other sources of blue light be present in our environment.

Thus blue light cuts both ways. During the day when we want to be alert, should the room you’re in be dimly lit, or it’s a long and gloomy winter day bereft of sunlight, then the lack of blue light will make you drowsy, and even depressed if absent long term. The flip side is that if blue light remains in your environment during the night when you want to wind down and prepare for sleep, it could interfere with sound and deep rest.

Light is not the only thing that resets our internal clock and affects our body. Another significant input is when we eat. And in the modern era, it turns out that when we eat may affect our circadian clock than as much as anything else in our environment.

What The Mice Tell Us

This is clearly demonstrated in mice studies. Numerous experiments have studied the effect on eating on twin mouse brothers. It’s been clearly demonstrated that if you give one set of twins high fat food and the other set healthy food, eventually the high fat cohort will become obese and the healthy diet cohort becomes healthy.

Makes perfect sense, but one particular detail tells the tale.

If the time of day the food is eaten is examined what has been discovered is that mice eating the healthy diet only ate during the night (its normal time for eating given that it’s a nocturnal animal), whereas the mice eating the high fat diet ate all the time, day and night.

(Sound familiar?)

These daytime fat-eating mice were eating the wrong food at the wrong time, and this was messing up their circadian clock such that their genes weren’t turning on and off at the right time. The question then became,

“Was it the fatty foods consumed or when they were consumed that caused the obesity… or both?”

More experimentation was needed.

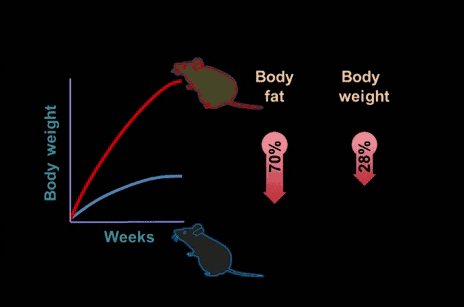

A test was set up to examine, again, identical mice; two groups (cohorts):

- One group could eat whenever they wanted; and

- The other group ate the same number of calories of the same high-fat diet every day at nighttime, their normal feeding time given that mice are nocturnal.

After several weeks went by, the two cohorts began to exhibit very different body compositions and physiology:

| Physiological Affects | |

| Group 1: Eat Whenever

|

Gained weight (obese), averaging 50 grams.

Fatty liver. |

| Group 2: Time Controlled Eating | Lost weight, mostly fat, and weighed 28% less than Group 1.

Better livers, blood sugar, blood cholesterol and athleticism than Group 1. |

Perhaps at this point you’re wondering if when you eat is more important than what you eat true for humans, as it is with mice?

Well, we’re not 100% sure about that, but pretty close. This will be tested in human trials, but my advice is not to wait for the results, because these mice findings make sense for us humans.

For all but the last 150 or so years, we evolved to wake up and sleep in concert with the Sun. We didn’t eat during the several hours between sundown and sleep, as many of us do now. We didn’t have access to food at whim, whenever, wherever.

Our bodies easily store fat because we needed to rely on using fat stores for caloric requirements during food shortages. Fasting was a regular experience. These days, fasting is a torment.

Dr. Panda’s work will continue to examine to what extent staying up and eating late into the night alters our internal clock, physiology and metabolism, such that we become fat and susceptible to chronic disease.

Watch and listen to what he has to say:

Your Takeaway

You know the mantra by now:

When you eat is more important than what you eat.

Some fine points:

- Eat as healthily as you can. (Here’s some guidance.)

- Don’t eat after 7:00 PM. Each week, stop eating 1/2 hour earlier till you get there.

- Every 24 hour period, give yourself at least 12 hours rest without eating (hours in the evening plus hours sleeping). (Read this about Intermittent Fasting.)

Last Updated on October 24, 2019 by Joe Garma