Plant Protein vs Animal Protein for Longevity, Part 3

The plant protein vs animal protein debate comes into clear focus when viewed through the prism of healthspan optimization. Over the long run, the science clearly shows that a diet rich in plant proteins will keep your motor running longer. Read on to discover why.

"Plant protein vs animal protein" is one of more than 30 lessons from the upcoming online video course that will show you how to reduce your biological age. Subscribe to the Newsletter to be notified when it's released.

The plant protein vs animal protein debate has a clear winner overall — plant protein. But don’t run away if you’re a lover of meat, because there are reasons to eat it. Generally speaking, the best source of protein for you depends on your age, your physical condition, and what you’re trying to achieve.

This is Part 3 of a three-part series about the macronutrients that best support longevity. Part 1 examined simple vs complex carbohydrates; Part 2 examined saturated vs unsaturated fats; and here in Part 3, the focus is on plant protein vs animal protein.

The intention of this post is to provide convincing evidence that:

- Plant protein is the best source of protein for general health and to support a long and robust healthspan.

- Although plant protein will support muscle growth, there is a role for animal protein consumption for the specific goal of improving protein muscle synthesis in cases where a person wants to quickly build muscle because they’re too weak, or suffer from sarcopenia, a condition common among the elderly.

- Most people in the industrialized world consume more than enough protein.

The experts who study protein can disagree on the relative merits of plant protein vs animal protein, but having read dozens of studies and articles on this subject, I believe that this disagreement largely emanates from the specific benefits under consideration, as you will soon see.

This post covers:

Plant Protein vs Animal Protein, A Quick Summary

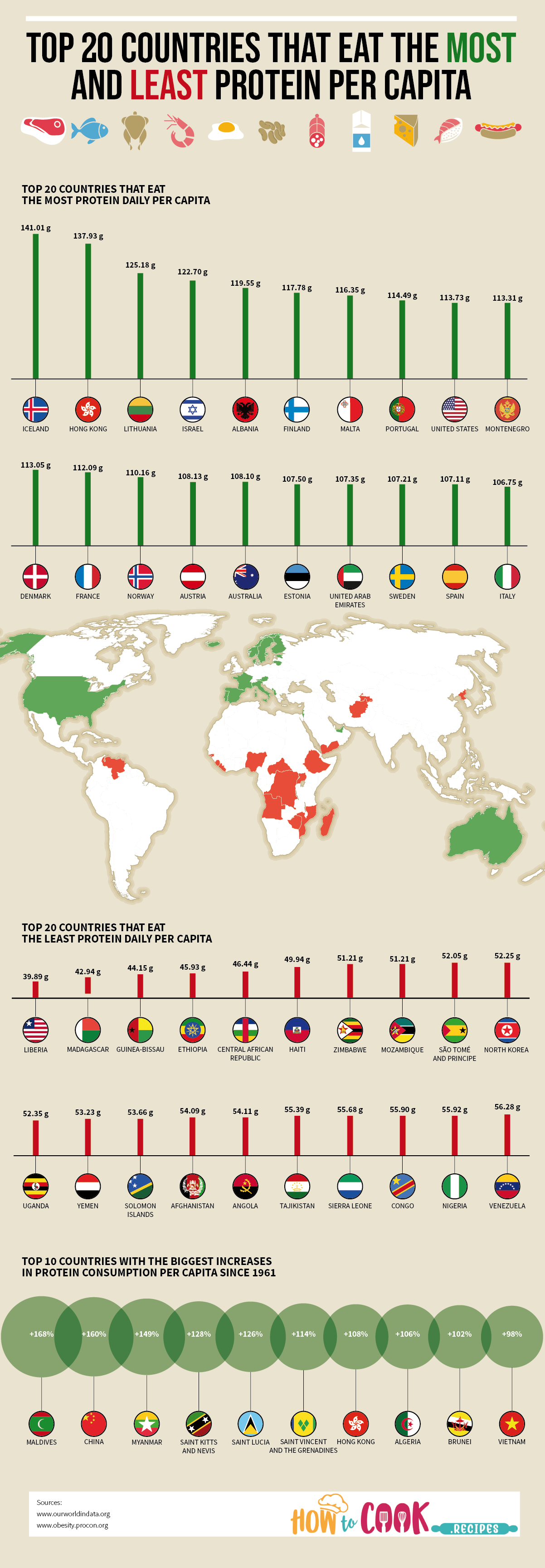

Before we get into the nitty gritty of this plant protein vs animal protein debate, let’s review a list of the pluses and minuses of each protein source.

Plant Protein Attributes

- Beans, soy, legumes, seeds and nuts provide enough protein to support health, but no one plant protein source contains all nine essential amino acids (the “building blocks” of proteins) as does animal protein; therefore, ideally they should be combined to provide a complete essential amino acid profile.

- Pound-for-pound, plant-based proteins will pack more nutrients into fewer calories.

- Plant proteins contain specific nutrients (phytonutrients), antioxidants and fiber, but animal proteins do not.

- Plant protein consumption along with a vegetarian/vegan diet results in a lowered risk of stroke, increased occurrence of weight loss (which helps to minimize many of the health issues related to obesity), a lowered risk for type-2 diabetes, cancer and heart disease, reduction in the risk of cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s, and dementia, and that their naturally-occurring antioxidants have been shown to help in the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases and in supporting the immune system [1].

- Replacing animal protein with plant-based protein lowers the risk of death from cancer and heart disease [2].

- A high plant protein diet supports muscle strength and mass gains just as well as one that includes animal protein [3].

Animal Protein Attributes

- Most animal proteins contain all nine essential amino acids.

- Animal protein generally provides better protein muscle synthesis than plant protein because it has more of the amino acid leucine.

- Animal protein is a common protein source than plant proteins in industrialized nations, and is used more often than plant proteins.

- Animal protein has little to no fiber, which is essential for gut health.

- Non-fish animal protein from mammals, eggs and full-fat diary is high in saturated fat, which can raise cholesterol levels and increase your risk of heart disease. [4]

- High meat consumption increases the risk of some cancers [5].

What do you do with this information so far?

A middle-of-the-road perspective is cited by the world-renown Mayo Clinic:

The healthiest protein options are plant sources, such as soy, nuts, seeds, beans and lentils; lean meats, such as skinless, white-meat chicken or turkey; a variety of fish or seafood; egg whites; or low-fat dairy.

That perspective, however, is not directed toward optimizing healthspan and longevity, because as you will soon see, a better option than the “middle of the road” suggestion by the Mayo Clinic is to eat more plant protein, and less meat protein, unless you have a special need for upregulating muscle protein synthesis.

How Much Protein Do You Need?

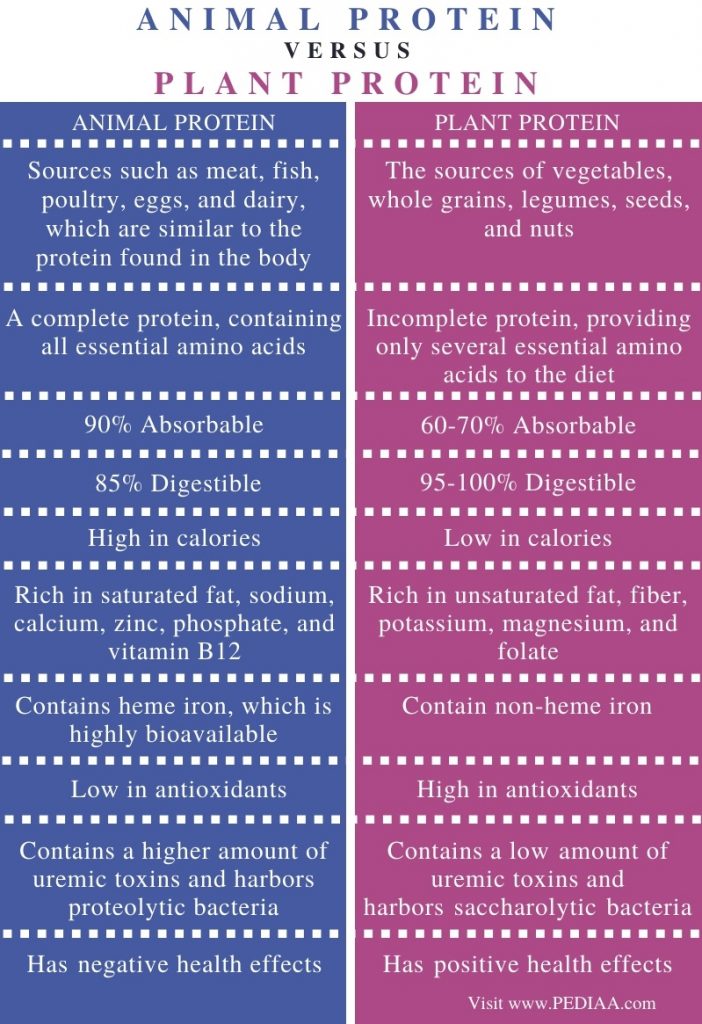

Protein makes up 16% of the average American’s diet, according to the CDC. That makes it ninth on the list of 20 top protein consuming countries at about 114 grams per person.

You can see from the infographic above that Americans consume a lot of protein, but eight other countries eat more.

I should point out that this data is largely based on polling, and some sources that I’ve reviewed show a bit more or less protein consumption.

Returning to the Mayo Clinic page on protein, the US RDA (recommended daily allowance) to prevent protein deficiency for an average sedentary adult is 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight. For example, a person who weighs 165 pounds, or 75 kilograms, should consume 60 grams of protein per day.

Six other pertinent observations made by the Mayo Clinic:

1. Most Americans are getting more protein than they need: Contrary to the drumbeat that everyone needs more protein, most people in the U.S. get enough, or more than they need. This is especially true for males ages 19 to 59. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 indicate that men in that age range are exceeding their protein recommendations, especially from meat, poultry and eggs.

2. The body can’t store protein: After your protein needs are met, any extra is used for energy or stored as fat. Excess calories from any source will be stored as fat in the body.

3. As you get older, you need more protein. If you do not do resistance training (weight lifting and/or calisthenics) somewhere between ages 40 to 50, sarcopenia (muscle wasting) begins to set in. To prevent this and to maintain independence and quality of life, your protein needs to increase to about 1 to 1.2 grams per kilogram or 75 to 90 grams per day for a 165-pound/75-kilogram person. One reason for this extra protein is that as we get older, protein muscle synthesis declines, as I will address later.

4. If you exercise you need more protein. This is especially true if the exercise is focused on breaking down muscle tissue, which performing calisthenics and weight lifting does. People who exercise regularly also have higher needs, about 1.1 to 1.5 grams per kilogram, says the Mayo Clinic. People who regularly lift weights, or are training for a running or cycling event need 1.2 to 1.7 grams per kilogram. Excessive protein intake would be more than two grams per kilogram of body weight each day. (Note: these numbers are excessive for sedentary people, or those you exercise infrequently and at low intensity.)

5. Excess protein can make you ill. Extra protein intake can lead to elevated blood lipids and heart disease because many high-protein foods you eat are high in total and saturated fat. Extra protein intake, which can tax the kidneys, poses an additional risk to people predisposed to kidney disease. Again, it’s noteworthy to point out that plant protein does not have saturated fat, nor does it have a few other attributes I’ll describe later that taxes healthspan as opposed to improving it.

6. You need to spread out protein consumption evenly throughout the day. This gets back to point number 2 — your body does not store protein, like it does with carbs, and dietary fat. Some newer studies show moving some protein from supper to breakfast can help with weight management by decreasing hunger and cravings throughout the day. This point supports the old adage “Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince and dinner like a pauper.”

I’m going to dive into some the details behind the Mayo Clinic’s claims, which perhaps for their suggestion about protein quantities for exercises, are spot on; but first I want you spell out the case for more protein consumption.

The Case for More Protein Consumption

It’s instructive to review the views of two respected scientists who support higher protein consumption, and they are:

- Stuart Phillips, PhD, a protein researcher and professor of kinesiology at McMaster University in Canada; and

- Peter Attia, MD, a cancer doctor who has become a longevity expert.

In an interview with the University of Auburn, Dr Phillips recommends that the protein intakes of older adults should be at least 1.2 g protein/kg/day (which is about 0.55 grams per pound), and likely up to the same level as younger folks. The main problem in aging is that muscle becomes ‘resistant’ to muscle protein synthesis (the uptake of protein into muscles), and therefore older people need to remain physically active, and consume sufficient amounts of protein to help them retain muscle and strength.

Dr. Phillips is saying at least 0.55 grams per pound of body weight, which is less than the US RDA’s recommendation of 0.8 grams per pound. Where Dr. Phillips diverges from the RDA is his recommendation for young weightlifters, who, he says, should aim for between 0.7 to 1 g protein/lb body weight/day (1.6 and 2.2 g protein/kg body weight/day), divided into three to four meals per day.

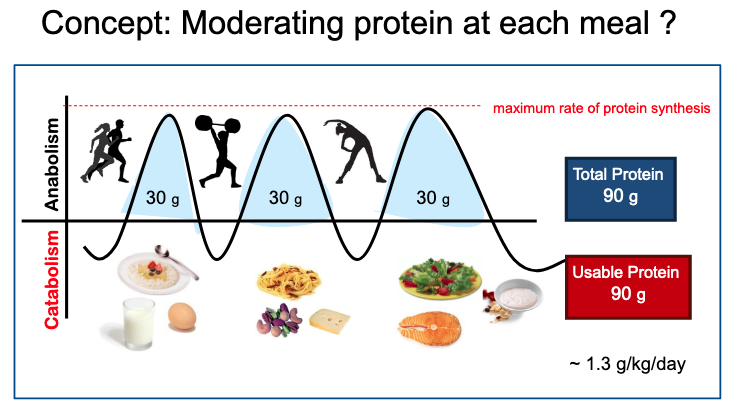

The reason Dr. Phillips is talking about even distribution of protein intake throughout the day is shown in this graph:

This graph comes from a presentation given by two scientists:

- Douglas Paddon-Jones, Ph.D., FACSM (Fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine), and

- Sheriden Lorenz Distinguished Professor of Aging and Health

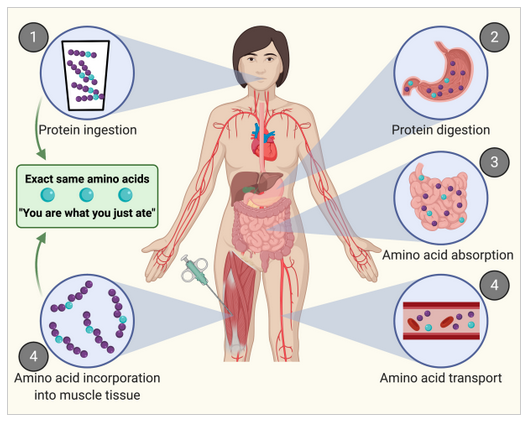

What the graph shows is that the maximum amount of protein your body can use at any given time is 30 grams, on average.

Say you’re doing some resistance training, which puts your body in a catabolic state since you’re breaking down muscle tissue, and then afterwards you eat protein, which puts you in an anabolic state since you’re building muscle tissue via muscle protein synthesis. If you eat more than 30 grams of protein at a time, the excess is not used for repair or growth, but instead gets broken down into carbs that are stored as glycogen and into ammonia that then needs to be processed by the kidneys.

Paddon- Jones and Lorenz think that the protein RDA of 0.8 is fine, but that it needs to increase for older adults, perhaps beginning at age 60 — particularly for highly active people — because in order to obtain 30 grams of protein, more than 30 grams needs to be eaten due to a decrease in muscle protein synthesis [6].

So far this is pretty much in alignment with the U.S. RDA and a bit below the Mayo Clinic’s recommendation, but one very smart fella disagrees — Peter Attia, MD.

Dr. Attia says that the RDA of 0.8 grams of protein per pound of body weight for adults is “pathetic”, and is likely predicated on how much protein you need to live life versus how much protein you need to thrive. He suggests that we need closer to two grams per kilogram, or about a gram per pound of body weight.

Now, like I did initially, you might be thinking, Huh, I don’t get it. What’s so “pathetic” about eating 0.2 grams per pound less (1 – 0.8) than the U.S. RDA? Well, do the math and see the difference: For a 175 pound person, that’s 35 grams less (175 x 0.2), which is about the protein content of one full meal at the RDA level.

Dr. Attia does acknowledge that excess protein consumption might be a challenge. He says that if you consume more protein than is usable, you’re going to overtax the kidneys that will have to work harder to excrete the excess nitrogen from the protein. However, this doesn’t concern him, because he thinks that healthy kidney function will not be challenged until you’re consuming 1.5 to 2 grams per pound (three to four grams per kilogram).

The problem is that kidney function doesn’t stay healthy for many of us as we get older, as I’ll touch on in a bit, but first let’s examine the case for consuming less protein.

The Case for Less Protein Consumption

From a longevity perspective, biogerontologist and cell biologist Dr. Valter Longo’s research indicates that longevity and healthspan are optimized by a low-protein pescaterain diet.

Based on his extensive research, Dr. Longo’s longevity diet suggests that you:

- Eat mostly vegan, plus a little fish, limiting meals with fish to a maximum of two or three per week. Choose fish, crustaceans, and mollusks with a high omega-3, omega-6, and vitamin B12 content (salmon, anchovies, sardines, cod, sea bream, trout, clams, shrimp. Pay attention to the quality of the fish, choosing those with low levels of mercury.

- If you are below the age of 65, keep protein intake low (0.31 to 0.36 grams per pound of body weight). That comes to 40 to 47 grams of proteins per day for a person weighing 130 pounds, and 60 to 70 grams of protein per day for someone weighing 200 to 220 pounds. Over age 65, you should slightly increase protein intake but also increase consumption of fish, eggs, white meat, and products derived from goats and sheep to preserve muscle mass. Consume beans, chickpeas, green peas, and other legumes as your main source of protein.

- Minimize saturated fats from animal and vegetable sources (meat, cheese) and sugar, and maximize good fats and complex carbs. Eat whole grains and high quantities of vegetables (tomatoes, broccoli, carrots, legumes, etc.) with generous amounts of olive oil (3 tablespoons per day) and nuts (1 ounce per day).

- Follow a diet with high vitamin and mineral content, supplemented with a multivitamin buffer every three days.

- Select ingredients among those discussed in this book that your ancestors would have eaten.

- Based on your weight, age, and abdominal circumference, decide whether to have two or three meals per day. If you are overweight or tend to gain weight easily, consume two meals a day: breakfast and either lunch or dinner, plus two low-sugar (less than 5 grams) snacks with fewer than 100 calories each. If you are already at a normal weight, or if you tend to lose weight easily or are over 65 and of normal weight, eat three meals a day and one low-sugar (less than 3 to 5 grams) snack with fewer than 100 calories.

- Confine all eating to within a twelve-hour period; for example, start after 8 a.m. and end before 8 p.m. Don’t eat anything within three to four hours of bedtime.

Yes, I went well beyond the protein quantity topic, but I wanted you to see what a comprehensive longevity diet looks like through the lens of a longevity researcher. For context, this diet most resembles that of the Okinawans, the longest-lived people on the planet, which I wrote about in my post, The Blue Zone Diet Will Transform You.

If by now you’re utterly confused about whether a high or low protein diet is best, I’ll tell you a way out of this dilemma:

Just get most of your protein from plants, make sure there’s protein in every meal, and don’t worry about the quantity.

The rest of this post underscores that suggestion.

Plant Protein vs Animal Protein: Muscle Protein Synthesis, FGF21, Methionine and Kidney Burden

Animal protein improves muscle protein synthesis, mainly because of the essential amino acid leucine, the most potent amino acid for this purpose [7]. Leucine is low in plant protein and high in animal protein. If you’re physically weak due to low muscle mass and/or are elderly and have sarcopenia, you may want to eat animal protein until you grow more muscle and get stronger. But for this to happen in any meaningful way, you must perform resistance training to some degree. (See my posts about building muscle.)

After you’ve improved your muscle composition, start replacing animal protein with plant protein. After detailing the reasons why red meat consumption is associated with an increased risk of total mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality and cancer mortality—meaning a significantly shorter lifespan — an important Harvard study reviewed by Dr. Michael Greger concluded:

“Go with plants. Eating a plant-based diet is healthiest.”

Beyond the benefits of reducing the risks of heart disease and cancer, plant protein consumption can upregulate a hormone secreted by the liver called FGF21, and downregulate a protein called methionine, an amino acid found predominantly in animal proteins that has an inverse relationship to cellular lifespan (lower methionine, longer lifespan.) [8].

As reviewed in Dr. Michael Greger’s video below, FGF21 is characterized as a systemic enhancer of longevity. It can be boosted through prolonged fasting, but an easier way to do it is by eating plant protein. If you eat starchy foods, your FGF21 levels increase. The healthiest sources are whole grains and beans, since butyrate appears to boost FGF21, too, and butyrate is produced by our gut’s bacteria as a byproduct of munching on fiber.

Other pertinent points made in the video:

- Circulating FGF21 levels are also increased dramatically when you eat a lower protein diet. Over 150% increase within four weeks.

- FGF21 has been proposed as a potential mediator of the protection from cancer, autoimmune diseases, obesity, and diabetes afforded by strictly plant-based diets.

- A study showed that the group that was protein-restricted to normal levels, but ate 300 more calories overall than the control group lost two more pounds of body fat, thanks to FGF21.

- A similar study found that taking men down to 73 grams a day of protein resulted in a six-fold increase in FGF21 within a single week, accompanied by a significant increase in insulin sensitivity. They conclude that “dietary protein dilution” promotes metabolic health in humans.

- The consumption of plant protein and the corresponding reduction in methionine is thought to be a strong FGF21 booster.

- FGF21 levels were markedly higher in vegan humans compared with omnivores, and they went up 232% when the omnivores were switched to vegetarian diets after just four days.

Finally, after mentioning the potential deleterious effects of excess consumption of animal protein on kidney function, let’s quickly explore this further.

The National Kidney Foundation reports that although kidney disease can develop at any time, those over the age of 60 are more likely than not to develop kidney disease.

According to recent estimates from researchers at Johns Hopkins University, more than 50% of people over the age of 75 are believed to have kidney disease. High-risk groups include those with diabetes, high blood pressure, and/or a family history of kidney failure.

I mention this because it’s unreasonable to assume that people consuming high animal protein diets will be able to excrete the excess nitrogen as they age; their kidney’s simply might not be up to the task. And, indeed, it’s the animal protein that is the culprit here.

According to this 2018 study published in the journal Nutrition, although the essential amino acids are important for kidney health, red meat consumption “may lead to elevated production of uremic toxins and increased cardiovascular risk… [and] is associated with increased risk for progression of CKD (chronic kidney disease).

Your Takeaway

We covered a lot of ground here, and I admit that it was rocky.

Just remember these three things:

- Plant protein is superior to animal protein in several important ways: it is void of saturated fat and high cholesterol that reduces many chronic illnesses that beset us as we age, has plentiful fiber that makes our gut happy, people tend to be leaner eating plant protein, and live longer.

- But animal protein does offer better muscle protein synthesis, and that may be important enough to temporarily consume animal protein if you need more muscle (not talking vanity here); for instance, if you have sarcopenia.

- As long as you consciously endeavor to eat a wide variety of plant food high in protein (beans, soy, lentils, seeds and nuts) at least twice per day, don’t worry about the amount of protein you’re eating. If, however, you’re eating a lot of animal protein, reduce your portions, and start substituting some of it with plant protein.

If you missed Part 1 about simple carbs vs complex carbs, go here; and for Part 2 about saturated fats vs unsaturated fats, go here.

Questions or comments? Scroll down to the Comments section and have at it.

Last Updated on September 29, 2022 by Joe Garma