The Best Exercises to Live Longer: Dr. Attia’s Outlive, Part 2

The best exercises to live longer include stability/mobility, cardiorespiratory and strength training. Dr. Peter Attia’s book, Outlive, explains why.

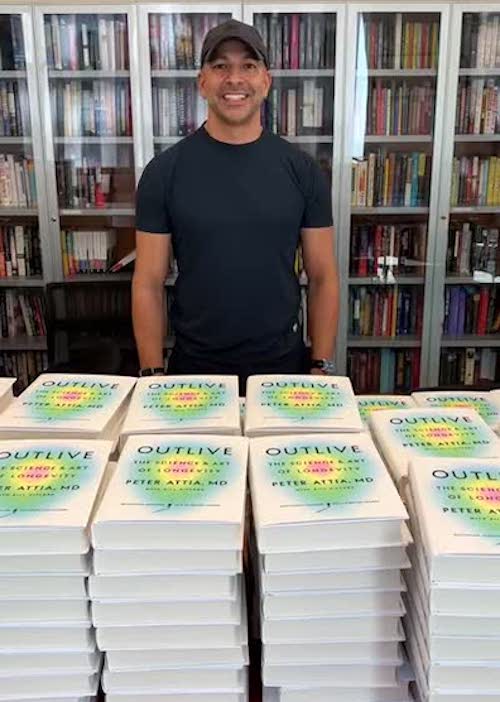

The best exercises to live longer is the focus of Part 2 of my review of Dr. Peter’s new book, Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity.

Anyone who has spent even a bit of time reading about Dr. Attia or watching his interviews knows that his number one prescription for improving healthspan is exercise:

“More than any other tactical domain we discuss in this book, exercise has the greatest power to determine how you will live out the rest of your life.”

Looming above anything else discussed in Outlive, Attia asserts that exercise has the greatest power to determine how you will live out the rest of your life. An overwhelming amount of data underscores this point, and, in fact, even a minimal amount of exercise can lengthen your life by several years.

Consistent exercise delays the onset of many chronic diseases, and is effective at extending and improving healthspan: it can reverse physical decline and slow or reverse cognitive decline as well. The bad news is that 77 percent of the US population does not exercise. The good news is that just going from zero weekly exercise to just 90 minutes per week can make a big difference in your quality of life as an old person.

Here are some facts about exercise that Attia underscores that hopefully focus your attention:

- Going from zero weekly exercise to just 90 minutes per week can reduce your risk of dying from all causes by 14 percent.

- Study after study has found that regular exercisers live as much as a decade longer than sedentary people.

- VO2 max, is perhaps the single most powerful marker for longevity. (VO2 max represents the maximum rate at which a person can utilize oxygen.)

- Whether by measures of cardiorespiratory capacity or muscular strength, the fitter you are the lower your risk of death.

Attia cites the work of Dr. John Ioannidis, Professor of Medicine at Stanford University who has run side-by-side comparisons between drug and exercise studies and found that in several randomized clinical

trials, exercise-oriented interventions performed as well or better than multiple classes of prescription drugs at reducing mortality from coronary heart disease, prediabetes/diabetes and stroke.

This is why, suggests Attia, exercise acts like a drug at the biochemical level:

- Exercise strengthens the heart and helps maintain the circulatory system.

- Exercise improves the health of the mitochondria, the crucial little organelles that produce energy in our cells via ATP, the energy used by cells.

- Improved mitochondria (mitochondrial biogenesis) improves our ability to metabolize both glucose and fat.

- More muscle mass and stronger muscles supports and protects the body, and maintains metabolic health, because muscles consume energy efficiently.

- Exercise prompts the body to produce its own endogenous drug-like chemicals, such as cytokines that help strengthen the immune system and stimulate the growth of new muscle and stronger bones.

- Exercise helps generate a potent molecule called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) that improves the health and function of the hippocampus, a part of the brain that plays an essential role in memory.

- Exercise helps keep the brain vasculature healthy, and it may also help preserve brain volume (important for reducing Alzheimer’s risk).

That begs the questions: Why and what type of exercise?

Well, as you would expect, Attia addresses those questions and more in three chapters of Outlive that primarily encompass:

- Cardiorespiratory fitness (its association with longevity),

- Muscular strength (its association with longevity), and

- Stability (its association with longevity).

Stability is the last chapter about exercise in his book, but I’m going to review some of what he says about it first, because it’s the first thing that’s needed in order to do various cardiorespiratory and strength training safely and effectively.

As I mentioned in Part 1, although Dr. Attia lists hundreds of references in his book, he does not footnote most of the statistics and studies he cites; therefore, except for a few instances, I don’t either. Nonetheless, in my opinion, when he says that a certain study says a certain thing, that study exists and he’s read it.

Another thing to point out is that this review does not provide a comprehensive look at Outlive; rather, the intention is to provide enough valuable information to persuade you to get the book and benefit from its pearls of wisdom.

With that in mind, let’s dig into the longevity-extending capacity of exercise, beginning with stability.

Stability: the Foundation for The Best Exercises to Live Longer

Dr. Attia addresses stability in his last chapter on exercise, after cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular strength, but I want to address it first, because you want to build the foundation. Irrespective of where he put this chapter in Outlive, Attia agrees:

“…I think of stability as the solid foundation that enables us to do everything else that we do, without getting injured. Stability makes us bulletproof.”

Think of stability as the innate “ability to harness, decelerate, or stop force”. A person that has developed stability can respond “to internal or external stimuli to adjust position and muscular tension appropriately without a tremendous amount of conscious thought.”

Stability enables our body to summon the necessary force safely to connect different muscle groups when needed with minimal risk of injury to joints,soft tissue, and our vulnerable spine. The aim is to be “strong, fluid, flexible, and agile as you move through your world”.

So, how do you develop stability?

You get help.

You can easily learn, say, to do a bicep curl by watching others, or getting some detailed instruction, because it’s a simple movement that can be self-corrected by watching yourself do the movement in a mirror. Many stability exercises, however, are not that easy; they can be subtle and nuanced, requiring exacting compound movements (multiple muscles and positions) that are difficult to observe in the mirror, and require sufficient self-awareness about your body’s movement patterns for correct application.

In Attia’s case, he is fortunate enough to have someone in his clinic who has expertly guided him in improving what he admits was a poor foundation of stability that was leading him to various injuries as he did his cardiorespiratory and strength training.

Dr. Peter Attia’s trainer, Beth Lewis, demonstrates a stand-to-sit mobility/stability drill. This is a screenshot from a video available to buyers of the book, Outlive.

What you could do is to find someone credentialed in dynamic neuromuscular stabilization (DNS), which aims “to retrain our bodies — and our brains — in those patterns of perfect movement that we learned as little kids”.

DNS encourages you to think of the abdomen as a cylinder, surrounded by a wall of muscle, with the diaphragm on top and the pelvic floor below. You inflate the cylinder with a deep inhalation that expands your chest, ribs, abdomen and back, as if they’re one big cylindrical balloon. Once this cylinder is inflated, you feel what’s called intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). When you learn to fully pressurize this cylinder via IAP, your movement pattern becomes more safe, because the cylinder stabilizes the spine.

Of course, your options are not limited to DNS. Another option is to be coached by a yoga teacher well versed in movement precision, or to be aided by a movement modality that is proven to help you gain stable movement patterns. Make sure that whatever modality you choose to help you become more stable and mobile involves breathwork.

You also need to think about your feet, says Attia:

“If the road to stability begins with the breath, it travels through the feet—the most fundamental point of contact between our bodies and the world.”

Foundational stability begins with your feet. Before you do any exercise where you’re on your feet, you must be aware of them and how they’re contributing to the stability (or not) of the movement. Attia spends a lot of time on this topic in Outlive, as he does with breathwork; suffice to say that your feet are the beginning of a chain of inter-connected links that move up from the feet to your ankles, knees, hips and spine.

You can get some idea about the importance of your feet for stability by checking your balance. Stand on one foot — can you balance for 30 seconds? Close your eyes while standing on one foot — can you balance for 15 seconds?

Cardiorespiratory Fitness Keeps Your Ticker Ticking

Cardiorespiratory fitness encompasses both aerobic and anaerobic capacity:

- Aerobic means ‘with air’ and refers to the body producing energy with the use of oxygen. This typically involves any exercise that lasts longer than two minutes in duration. Continuous ‘steady state’, Zone 2 exercise is performed aerobically. Think 5 kilometer jun.

- Anaerobic means ‘without air’ and refers to the body producing energy without oxygen, which then constrains the exercise effort to just a few minutes or shorter. Think 100 meter sprint.

So, cardiorespiratory fitness requires training that encompasses long, steady state endurance work, such as jogging or cycling or swimming (Zone 2), and maximal efforts over shorter periods (typically four minutes or shorter), where VO2 max comes into play.

Good cardiorespiratory fitness is valuable in order to attain a high quality of life as you get older. A study published in 2020 by the Journal of the American College Cardiology that studied a cohort of 750,302 US male and female veterans aged 30 to 95 years came to the same conclusions as many other such studies:

- Cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is inversely associated with all-cause mortality (more fitness = less death)

- Traditional risk factors like chronic kidney disease, smoking, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and age all were independently linked to increased mortality risk — but none as strongly as cardiorespiratory fitness.

- Those in the extremely fit cohort had the greatest survival. The lowest mortality risk was observed in people with exercise capacity of 14.0 METs. (METS, metabolic equivalents: One MET is defined as the energy you use when you’re resting or sitting still per minute. I wrote METs and VO2 max here.)

Click here to see an exhaustive list of METs activities -- which do you do? (Click again to close.)

This list is from Britannica ProCon.org.

Remember: “Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) values are a way to estimate how many calories are burned during a specific physical activity, according to the American Council on Exercise. This table shows the MET values that researchers have assigned to various activities. A higher value correlates with more oxygen used by the body during that activity, so running has a higher MET value than sitting still.”

| Activity | Specific Motion | METs |

|---|---|---|

| bicycling | bicycling, mountain, uphill, vigorous | 14 |

| bicycling | bicycling, mountain, competitive, racing | 16 |

| bicycling | bicycling, BMX | 8.5 |

| bicycling | bicycling, mountain, general | 8.5 |

| bicycling | bicycling, <10 mph, leisure, to work or for pleasure | 4 |

| bicycling | bicycling, to/from work, self selected pace | 6.8 |

| bicycling | bicycling, on dirt or farm road, moderate pace | 5.8 |

| bicycling | bicycling, general | 7.5 |

| bicycling | bicycling, leisure, 5.5 mph | 3.5 |

| bicycling | bicycling, leisure, 9.4 mph | 5.8 |

| bicycling | bicycling, 10-11.9 mph, leisure, slow, light effort | 6.8 |

| bicycling | bicycling, 12-13.9 mph, leisure, moderate effort | 8 |

| bicycling | bicycling, 14-15.9 mph, racing or leisure, fast, vigorous effort | 10 |

| bicycling | bicycling, 16-19 mph, racing/not drafting or > 19 mph drafting, very fast, racing general | 12 |

| bicycling | bicycling, > 20 mph, racing, not drafting | 15.8 |

| bicycling | bicycling, 12 mph, seated, hands on brake hoods or bar drops, 80 rpm | 8.5 |

| bicycling | bicycling, 12 mph, standing, hands on brake hoods, 60 rpm | 9 |

| bicycling | unicycling | 5 |

| conditioning exercise | activity promoting video game (e.g., Wii Fit), light effort (e.g., balance, yoga) | 2.3 |

| conditioning exercise | activity promoting video game (e.g., Wii Fit), moderate effort (e.g., aerobic, resistance) | 3.8 |

| conditioning exercise | activity promoting video/arcade game (e.g., Exergaming, Dance Dance Revolution), vigorous effort | 7.2 |

| conditioning exercise | army type obstacle course exercise, boot camp training program | 5 |

| conditioning exercise | bicycling, stationary, general | 7 |

| conditioning exercise | bicycling, stationary, 30-50 watts, very light to light effort | 3.5 |

| conditioning exercise | bicycling, stationary, 90-100 watts, moderate to vigorous effort | 6.8 |

| conditioning exercise | bicycling, stationary, 101-160 watts, vigorous effort | 8.8 |

| conditioning exercise | bicycling, stationary, 161-200 watts, vigorous effort | 11 |

| conditioning exercise | bicycling, stationary, 201-270 watts, very vigorous effort | 14 |

| conditioning exercise | bicycling, stationary, 51-89 watts, light-to-moderate effort | 4.8 |

| conditioning exercise | bicycling, stationary, RPM/Spin bike class | 8.5 |

| conditioning exercise | calisthenics (e.g., push ups, sit ups, pull-ups, jumping jacks), vigorous effort | 8 |

| conditioning exercise | calisthenics (e.g., push ups, sit ups, pull-ups, lunges), moderate effort | 3.8 |

| conditioning exercise | calisthenics (e.g., situps, abdominal crunches), light effort | 2.8 |

| conditioning exercise | calisthenics, light or moderate effort, general (e.g., back exercises), going up & down from floor ( 150) | 3.5 |

| conditioning exercise | circuit training, moderate effort | 4.3 |

| conditioning exercise | circuit training, including kettlebells, some aerobic movement with minimal rest, general, vigorous intensity | 8 |

| conditioning exercise | CurvesTM exercise routines in women | 3.5 |

| conditioning exercise | Elliptical trainer, moderate effort | 5 |

| conditioning exercise | resistance training (weight lifting, free weight, nautilus or universal), power lifting or body building, vigorous effort | 6 |

| conditioning exercise | resistance (weight) training, squats , slow or explosive effort | 5 |

| conditioning exercise | resistance (weight) training, multiple exercises, 8-15 repetitions at varied resistance | 3.5 |

| conditioning exercise | health club exercise, general | 5.5 |

| conditioning exercise | health club exercise classes, general, gym/weight training combined in one visit | 5 |

| conditioning exercise | health club exercise, conditioning classes | 7.8 |

| conditioning exercise | home exercise, general | 3.8 |

| conditioning exercise | stair-treadmill ergometer, general | 9 |

| conditioning exercise | rope skipping, general | 12.3 |

| conditioning exercise | rowing, stationary ergometer, general, vigorous effort | 6 |

| conditioning exercise | rowing, stationary, general, moderate effort | 4.8 |

| conditioning exercise | rowing, stationary, 100 watts, moderate effort | 7 |

| conditioning exercise | rowing, stationary, 150 watts, vigorous effort | 8.5 |

| conditioning exercise | rowing, stationary, 200 watts, very vigorous effort | 12 |

| conditioning exercise | ski machine, general | 6.8 |

| conditioning exercise | slide board exercise, general | 11 |

| conditioning exercise | slimnastics, jazzercise | 6 |

| conditioning exercise | stretching, mild | 2.3 |

| conditioning exercise | pilates, general | 3 |

| conditioning exercise | teaching exercise class (e.g., aerobic, water) | 6.8 |

| conditioning exercise | therapeutic exercise ball, Fitball exercise | 2.8 |

| conditioning exercise | upper body exercise, arm ergometer | 2.8 |

| conditioning exercise | upper body exercise, stationary bicycle – Airdyne (arms only) 40 rpm, moderate | 4.3 |

| conditioning exercise | water aerobics, water calisthenics, water exercise | 5.3 |

| conditioning exercise | whirlpool, sitting | 1.3 |

| conditioning exercise | video exercise workouts, TV conditioning programs (e.g., yoga, stretching), light effort | 2.3 |

| conditioning exercise | video exercise workouts, TV conditioning programs (e.g., cardio-resistance), moderate effort | 4 |

| conditioning exercise | video exercise workouts, TV conditioning programs (e.g., cardio-resistance), vigorous effort | 6 |

| conditioning exercise | yoga, Hatha | 2.5 |

| conditioning exercise | yoga, Power | 4 |

| conditioning exercise | yoga, Nadisodhana | 2 |

| conditioning exercise | yoga, Surya Namaskar | 3.3 |

| conditioning exercise | native New Zealander physical activities (e.g., Haka Powhiri, Moteatea, Waita Tira, Whakawatea, etc.), general, moderate effort | 5.3 |

| conditioning exercise | native New Zealander physical activities (e.g., Haka, Taiahab), general, vigorous effort | 6.8 |

| dancing | ballet, modern, or jazz, general, rehearsal or class | 5 |

| dancing | ballet, modern, or jazz, performance, vigorous effort | 6.8 |

| dancing | tap | 4.8 |

| dancing | aerobic, general | 7.3 |

| dancing | aerobic, step, with 6 – 8 inch step | 7.5 |

| dancing | aerobic, step, with 10 – 12 inch step | 9.5 |

| dancing | aerobic, step, with 4-inch step | 5.5 |

| dancing | bench step class, general | 8.5 |

| dancing | aerobic, low impact | 5 |

| dancing | aerobic, high impact | 7.3 |

| dancing | aerobic dance wearing 10-15 lb weights | 10 |

| dancing | ethnic or cultural dancing (e.g., Greek, Middle Eastern, hula, salsa, merengue, bamba y plena, flamenco, belly, and swing) | 4.5 |

| dancing | ballroom, fast | 5.5 |

| dancing | general dancing (e.g., disco, folk, Irish step dancing, line dancing, polka, contra, country) | 7.8 |

| dancing | ballroom dancing, competitive, general | 11.3 |

| dancing | ballroom, slow (e.g., waltz, foxtrot, slow dancing, samba, tango, 19th century dance, mambo, cha cha) | 3 |

| dancing | Anishinaabe Jingle Dancing | 5.5 |

| dancing | Caribbean dance (Abakua, Beguine, Bellair, Bongo, Brukin’s, Caribbean Quadrills, Dinki Mini, Gere, Gumbay, Ibo, Jonkonnu, Kumina, Oreisha, Jambu) | 3.5 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing, general | 3.5 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing, crab fishing | 4.5 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing, catching fish with hands | 4 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing related, digging worms, with shovel | 4.3 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing from river bank and walking | 4 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing from boat or canoe, sitting | 2 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing from river bank, standing | 3.5 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing in stream, in waders | 6 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing, ice, sitting | 2 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing, jog or line, standing, general | 1.8 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing, dip net, setting net and retrieving fish, general | 3.5 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing, set net, setting net and retrieving fish, general | 3.8 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing, fishing wheel, setting net and retrieving fish, general | 3 |

| fishing and hunting | fishing with a spear, standing | 2.3 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, bow and arrow, or crossbow | 2.5 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, deer, elk, large game | 6 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting large game, dragging carcass | 11.3 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting large marine animals | 4 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting large game, from a hunting stand, limited walking | 2.5 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting large game from a car, plane, or boat | 2 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, duck, wading | 2.5 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, flying fox, squirrel | 3 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, general | 5 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, pheasants or grouse | 6 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, birds | 3.3 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, rabbit, squirrel, prairie chick, raccoon, small game | 5 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, pigs, wild | 3.3 |

| fishing and hunting | trapping game, general | 2 |

| fishing and hunting | hunting, hiking with hunting gear | 9.5 |

| fishing and hunting | pistol shooting or trap shooting, standing | 2.5 |

| fishing and hunting | rifle exercises, shooting, lying down | 2.3 |

| fishing and hunting | rifle exercises, shooting, kneeling or standing | 2.5 |

| home activities | cleaning, sweeping carpet or floors, general | 3.3 |

| home activities | cleaning, sweeping, slow, light effort | 2.3 |

| home activities | cleaning, sweeping, slow, moderateeffort | 3.8 |

| home activities | cleaning, heavy or major (e.g. wash car, wash windows, clean garage), moderate effort | 3.5 |

| home activities | cleaning, mopping, standing, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| home activities | cleaning windows, washing windows, general | 3.2 |

| home activities | mopping, standing, light effort | 2.5 |

| home activities | polishing floors, standing, walking slowly, using electric polishing machine | 4.5 |

| home activities | multiple household tasks all at once, light effort | 2.8 |

| home activities | multiple household tasks all at once, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| home activities | multiple household tasks all at once, vigorous effort | 4.3 |

| home activities | cleaning, house or cabin, general, moderate effort | 3.3 |

| home activities | dusting or polishing furniture, general | 2.3 |

| home activities | kitchen activity, general, (e.g., cooking, washing dishes, cleaning up), moderate effort | 3.3 |

| home activities | cleaning, general (straightening up, changing linen, carrying out trash, light effort | 2.5 |

| home activities | wash dishes, standing or in general (not broken into stand/walk components) | 1.8 |

| home activities | wash dishes, clearing dishes from table, walking, light effort | 2.5 |

| home activities | vacuuming, general, moderate effort | 3.3 |

| home activities | butchering animals, small | 3 |

| home activities | butchering animal, large, vigorous effort | 6 |

| home activities | cutting and smoking fish, drying fish or meat | 2.3 |

| home activities | tanning hides, general | 4 |

| home activities | cooking or food preparation, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| home activities | cooking or food preparation – standing or sitting or in general (not broken into stand/walk components), manual appliances, light effort | 2 |

| home activities | serving food, setting table, implied walking or standing | 2.5 |

| home activities | cooking or food preparation, walking | 2.5 |

| home activities | feeding household animals | 2.5 |

| home activities | putting away groceries (e.g. carrying groceries, shopping without a grocery cart), carrying packages | 2.5 |

| home activities | carrying groceries upstairs | 7.5 |

| home activities | cooking Indian bread on an outside stove | 3 |

| home activities | food shopping with or without a grocery cart, standing or walking | 2.3 |

| home activities | non-food shopping, with or without a cart, standing or walking | 2.3 |

| home activities | ironing | 1.8 |

| home activities | knitting, sewing, light effort, wrapping presents, sitting | 1.3 |

| home activities | sewing with a machine | 2.8 |

| home activities | laundry, fold or hang clothes, put clothes in washer or dryer, packing suitcase, washing clothes by hand, implied standing, light effort | 2 |

| home activities | laundry, hanging wash, washing clothes by hand, moderate effort | 4 |

| home activities | laundry, putting away clothes, gathering clothes to pack, putting away laundry, implied walking | 2.3 |

| home activities | making bed, changing linens | 3.3 |

| home activities | maple syruping/sugar bushing (including carrying buckets, carrying wood) | 5 |

| home activities | moving furniture, household items, carrying boxes | 5.8 |

| home activities | moving, lifting light loads | 5 |

| home activities | organizing room | 4.8 |

| home activities | scrubbing floors, on hands and knees, scrubbing bathroom, bathtub, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| home activities | scrubbing floors, on hands and knees, scrubbing bathroom, bathtub, light effort | 2 |

| home activities | scrubbing floors, on hands and knees, scrubbing bathroom, bathtub, vigorous effort | 6.5 |

| home activities | sweeping garage, sidewalk or outside of house | 4 |

| home activities | standing, packing/unpacking boxes, occasional lifting of lightweight household items, loading or unloading items in car, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| home activities | implied walking, putting away household items, moderate effort | 3 |

| home activities | watering plants | 2.5 |

| home activities | building a fire inside | 2.5 |

| home activities | moving household items upstairs, carrying boxes or furniture | 9 |

| home activities | standing, light effort tasks (pump gas, change light bulb, etc.) | 2 |

| home activities | walking, moderate effort tasks, non-cleaning (readying to leave, shut/lock doors, close windows, etc.) | 3.5 |

| home activities | sitting, playing with child(ren), light effort, only active periods | 2.2 |

| home activities | standing, playing with child(ren) light effort, only active periods | 2.8 |

| home activities | walking/running, playing with child(ren), moderate effort, only active periods | 3.5 |

| home activities | walking/running, playing with child(ren), vigorous effort, only active periods | 5.8 |

| home activities | walking and carrying small child, child weighing 15 lbs or more | 3 |

| home activities | walking and carrying small child, child weighing less than 15 lbs | 2.3 |

| home activities | standing, holding child | 2 |

| home activities | child care, infant, general | 2.5 |

| home activities | child care, sitting/kneeling (e.g., dressing, bathing, grooming, feeding, occasional lifting of child), light effort, general | 2 |

| home activities | child care, standing (e.g., dressing, bathing, grooming, feeding, occasional lifting of child), moderate effort | 3 |

| home activities | reclining with baby | 1.5 |

| home activities | breastfeeding, sitting or reclining | 2 |

| home activities | sit, playing with animals, light effort, only active periods | 2.5 |

| home activities | stand, playing with animals, light effort, only active periods | 2.8 |

| home activities | walk/run, playing with animals, general, light effort, only active periods | 3 |

| home activities | walk/run, playing with animals, moderate effort, only active periods | 4 |

| home activities | walk/run, playing with animals, vigorous effort, only active periods | 5 |

| home activities | standing, bathing dog | 3.5 |

| home activities | animal care, household animals, general | 2.3 |

| home activities | elder care, disabled adult, bathing, dressing, moving into and out of bed, only active periods | 4 |

| home activities | elder care, disabled adult, feeding, combing hair, light effort, only active periods | 2.3 |

| home repair | airplane repair | 3 |

| home repair | automobile body work | 4 |

| home repair | automobile repair, light or moderate effort | 3.3 |

| home repair | carpentry, general, workshop | 3 |

| home repair | carpentry, outside house, installing rain gutters,carpentry, outside house, building a fence | 6 |

| home repair | carpentry, outside house, building a fence | 3.8 |

| home repair | carpentry, finishing or refinishing cabinets or furniture | 3.3 |

| home repair | carpentry, sawing hardwood | 6 |

| home repair | carpentry, home remodeling tasks, moderate effort | 4 |

| home repair | carpentry, home remodeling tasks, light effort | 2.3 |

| home repair | caulking, chinking log cabin | 5 |

| home repair | caulking, except log cabin | 4.5 |

| home repair | cleaning gutters | 5 |

| home repair | excavating garage | 5 |

| home repair | hanging storm windows | 5 |

| home repair | hanging sheet rock inside house | 5 |

| home repair | hammering nails | 3 |

| home repair | home repair, general, light effort | 2.5 |

| home repair | home repair, general, moderate effort | 4.5 |

| home repair | home repair, general, vigorous effort | 6 |

| home repair | laying or removing carpet | 4.5 |

| home repair | laying tile or linoleum,repairing appliances | 3.8 |

| home repair | repairing appliances | 3 |

| home repair | painting, outside home | 5 |

| home repair | painting inside house,wallpapering, scraping paint | 3.3 |

| home repair | painting | 4.5 |

| home repair | plumbing, general | 3 |

| home repair | put on and removal of tarp – sailboat | 3 |

| home repair | roofing | 6 |

| home repair | sanding floors with a power sander | 4.5 |

| home repair | scraping and painting sailboat or powerboat | 4.5 |

| home repair | sharpening tools | 2 |

| home repair | spreading dirt with a shovel | 5 |

| home repair | washing and waxing hull of sailboat or airplane | 4.5 |

| home repair | washing and waxing car | 2 |

| home repair | washing fence, painting fence, moderate effort | 4.5 |

| home repair | wiring, tapping-splicing | 3.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | lying quietly and watching television | 1 |

| inactivity quiet/light | lying quietly, doing nothing, lying in bed awake, listening to music (not talking or reading) | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | sitting quietly and watching television | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | sitting quietly, general | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | sitting quietly, fidgeting, general, fidgeting hands | 1.5 |

| inactivity quiet/light | sitting, fidgeting feet | 1.8 |

| inactivity quiet/light | sitting, smoking | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | sitting, listening to music (not talking or reading) or watching a movie in a theater | 1.5 |

| inactivity quiet/light | sitting at a desk, resting head in hands | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | sleeping | 0.95 |

| inactivity quiet/light | standing quietly, standing in a line | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | standing, fidgeting | 1.8 |

| inactivity quiet/light | reclining, writing | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | reclining, talking or talking on phone | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | reclining, reading | 1.3 |

| inactivity quiet/light | meditating | 1 |

| lawn and garden | carrying, loading or stacking wood, loading/unloading or carrying lumber, light-to-moderate effort | 3.3 |

| lawn and garden | carrying, loading or stacking wood, loading/unloading or carrying lumber | 5.5 |

| lawn and garden | chopping wood, splitting logs, moderate effort | 4.5 |

| lawn and garden | chopping wood, splitting logs, vigorous effort | 6.3 |

| lawn and garden | clearing light brush, thinning garden, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| lawn and garden | clearing brush/land, undergrowth, or ground, hauling branches, wheelbarrow chores, vigorous effort | 6.3 |

| lawn and garden | digging sandbox, shoveling sand | 5 |

| lawn and garden | digging, spading, filling garden, composting, light-to-moderate effort | 3.5 |

| lawn and garden | digging, spading, filling garden, compositing | 5 |

| lawn and garden | digging, spading, filling garden, composting, vigorous effort | 7.8 |

| lawn and garden | driving tractor | 2.8 |

| lawn and garden | felling trees, large size | 8.3 |

| lawn and garden | felling trees, small-medium size | 5.3 |

| lawn and garden | gardening with heavy power tools, tilling a garden, chain saw | 5.8 |

| lawn and garden | gardening, using containers, older adults > 60 years | 2.3 |

| lawn and garden | irrigation channels, opening and closing ports | 4 |

| lawn and garden | laying crushed rock | 6.3 |

| lawn and garden | laying sod | 5 |

| lawn and garden | mowing lawn, general | 5.5 |

| lawn and garden | mowing lawn, riding mower | 2.5 |

| lawn and garden | mowing lawn, walk, hand mower | 6 |

| lawn and garden | mowing lawn, walk, power mower, moderate or vigorous effort | 5 |

| lawn and garden | mowing lawn, power mower, light or moderate effort | 4.5 |

| lawn and garden | operating snow blower, walking | 2.5 |

| lawn and garden | planting, potting, transplanting seedlings or plants, light effort | 2 |

| lawn and garden | planting seedlings, shrub, stooping, moderate effort | 4.3 |

| lawn and garden | planting crops or garden, stooping, moderate effort | 4.3 |

| lawn and garden | planting trees | 4.5 |

| lawn and garden | raking lawn or leaves, moderate effort | 3.8 |

| lawn and garden | raking lawn | 4 |

| lawn and garden | raking roof with snow rake | 4 |

| lawn and garden | riding snow blower | 3 |

| lawn and garden | sacking grass, leaves | 4 |

| lawn and garden | shoveling dirt or mud | 5.5 |

| lawn and garden | shoveling snow, by hand, moderate effort | 5.3 |

| lawn and garden | shoveling snow, by hand | 6 |

| lawn and garden | shoveling snow, by hand, vigorous effort | 7.5 |

| lawn and garden | trimming shrubs or trees, manual cutter | 4 |

| lawn and garden | trimming shrubs or trees, power cutter, using leaf blower, edge, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| lawn and garden | walking, applying fertilizer or seeding a lawn, push applicator | 3 |

| lawn and garden | watering lawn or garden, standing or walking | 1.5 |

| lawn and garden | weeding, cultivating garden, light-to-moderate effort | 3.5 |

| lawn and garden | weeding, cultivating garden | 4.5 |

| lawn and garden | weeding, cultivating garden, using a hoe, moderate-to-vigorous effort | 5 |

| lawn and garden | gardening, general, moderate effort | 3.8 |

| lawn and garden | picking fruit off trees, picking fruits/vegetables, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| lawn and garden | picking fruit off trees, gleaning fruits, picking fruits/vegetables, climbing ladder to pick fruit, vigorous effort | 4.5 |

| lawn and garden | implied walking/standing – picking up yard, light, picking flowers or vegetables | 3.3 |

| lawn and garden | walking, gathering gardening tools | 3 |

| lawn and garden | wheelbarrow, pushing garden cart or wheelbarrow | 5.5 |

| lawn and garden | yard work, general, light effort | 3 |

| lawn and garden | yard work, general, moderate effort | 4 |

| lawn and garden | yard work, general, vigorous effort | 6 |

| miscellaneous | board game playing, sitting | 1.5 |

| miscellaneous | casino gambling, standing | 2.5 |

| miscellaneous | card playing,sitting | 1.5 |

| miscellaneous | chess game, sitting | 1.5 |

| miscellaneous | copying documents, standing | 1.5 |

| miscellaneous | drawing, writing, painting, standing | 1.8 |

| miscellaneous | laughing, sitting | 1 |

| miscellaneous | sitting, reading, book, newspaper, etc. | 1.3 |

| miscellaneous | sitting, writing, desk work, typing | 1.3 |

| miscellaneous | sitting, playing traditional video game, computer game | 1 |

| miscellaneous | standing, talking in person, on the phone, computer, or text messaging, light effort | 1.8 |

| miscellaneous | sitting, talking in person, on the phone, computer, or text messaging, light effort | 1.5 |

| miscellaneous | sitting, studying, general, including reading and/or writing, light effort | 1.3 |

| miscellaneous | sitting, in class, general, including note-taking or class discussion | 1.8 |

| miscellaneous | standing, reading | 1.8 |

| miscellaneous | standing, miscellaneous | 2.5 |

| miscellaneous | sitting, arts and crafts, carving wood, weaving, spinning wool, light effort | 1.8 |

| miscellaneous | sitting, arts and crafts, carving wood, weaving, spinning wool, moderate effort | 3 |

| miscellaneous | standing, arts and crafts, sand painting, carving, weaving, light effort | 2.5 |

| miscellaneous | standing, arts and crafts, sand painting, carving, weaving, moderate effort | 3.3 |

| miscellaneous | standing, arts and crafts, sand painting, carving, weaving, vigorous effort | 3.5 |

| miscellaneous | retreat/family reunion activities involving sitting, relaxing, talking, eating | 1.8 |

| miscellaneous | retreat/family reunion activities involving playing games with children | 3 |

| miscellaneous | touring/traveling/vacation involving riding in a vehicle | 2 |

| miscellaneous | touring/traveling/vacation involving walking | 3.5 |

| miscellaneous | camping involving standing, walking, sitting, light-to-moderate effort | 2.5 |

| miscellaneous | sitting at a sporting event, spectator | 1.5 |

| music playing | accordion, sitting | 1.8 |

| music playing | cello, sitting | 2.3 |

| music playing | conducting orchestra, standing | 2.3 |

| music playing | double bass, standing | 2.5 |

| music playing | drums, sitting | 3.8 |

| music playing | drumming (e.g., bongo, conga, benbe), moderate, sitting | 3 |

| music playing | flute, sitting | 2 |

| music playing | horn, standing | 1.8 |

| music playing | piano, sitting | 2.3 |

| music playing | playing musical instruments, general | 2 |

| music playing | organ, sitting | 2 |

| music playing | trombone, standing | 3.5 |

| music playing | trumpet, standing | 1.8 |

| music playing | violin, sitting | 2.5 |

| music playing | woodwind, sitting | 1.8 |

| music playing | guitar, classical, folk, sitting | 2 |

| music playing | guitar, rock and roll band, standing | 3 |

| music playing | marching band, baton twirling, walking, moderate pace, general | 4 |

| music playing | marching band, playing an instrument, walking, brisk pace, general | 5.5 |

| music playing | marching band, drum major, walking | 3.5 |

| occupation | active workstation, treadmill desk, walking | 2.3 |

| occupation | airline flight attendant | 3 |

| occupation | bakery, general, moderate effort | 4 |

| occupation | bakery, light effort | 2 |

| occupation | bookbinding | 2.3 |

| occupation | building road, driving heavy machinery | 6 |

| occupation | building road, directing traffic, standing | 2 |

| occupation | carpentry, general, light effort | 2.5 |

| occupation | carpentry, general, moderate effort | 4.3 |

| occupation | carpentry, general, heavy or vigorous effort | 7 |

| occupation | carrying heavy loads (e.g., bricks, tools) | 8 |

| occupation | carrying moderate loads up stairs, moving boxes 25-49 lbs | 8 |

| occupation | chambermaid, hotel housekeeper, making bed, cleaning bathroom, pushing cart | 4 |

| occupation | coal mining, drilling coal, rock | 5.3 |

| occupation | coal mining, erecting supports | 5 |

| occupation | coal mining, general | 5.5 |

| occupation | coal mining, shoveling coal | 6.3 |

| occupation | cook, chef | 2.5 |

| occupation | construction, outside, remodeling, new structures (e.g., roof repair, miscellaneous) | 4 |

| occupation | custodial work, light effort (e.g., cleaning sink and toilet, dusting, vacuuming, light cleaning) | 2.3 |

| occupation | custodial work, moderate effort (e.g., electric buffer, feathering arena floors, mopping, taking out trash, vacuuming) | 3.8 |

| occupation | electrical work (e.g., hook up wire, tapping-splicing) | 3.3 |

| occupation | engineer (e.g., mechanical or electrical) | 1.8 |

| occupation | farming, vigorous effort (e.g., baling hay, cleaning barn) | 7.8 |

| occupation | farming, moderate effort (e.g., feeding animals, chasing cattle by walking and/or horseback, spreading manure, harvesting crops) | 4.8 |

| occupation | farming, light effort (e.g., cleaning animal sheds, preparing animal feed) | 2 |

| occupation | farming, driving tasks (e.g., driving tractor or harvester) | 2.8 |

| occupation | farming, feeding small animals | 3.5 |

| occupation | farming, feeding cattle, horses | 4.3 |

| occupation | farming, hauling water for animals, general hauling water,farming, general hauling water | 4.3 |

| occupation | farming, taking care of animals (e.g., grooming, brushing, shearing sheep, assisting with birthing, medical care, branding), general | 4.5 |

| occupation | farming, rice, planting, grain milling activities | 3.8 |

| occupation | farming, milking by hand, cleaning pails, moderate effort | 3.5 |

| occupation | farming, milking by machine, light effort | 1.3 |

| occupation | fire fighter, general | 8 |

| occupation | fire fighter, rescue victim, automobile accident, using pike pole | 6.8 |

| occupation | fire fighter, raising and climbing ladder with full gear, simulated fire suppression | 8 |

| occupation | fire fighter, hauling hoses on ground, carrying/hoisting equipment, breaking down walls etc., wearing full gear | 9 |

| occupation | fishing, commercial, light effort | 3.5 |

| occupation | fishing, commercial, moderate effort | 5 |

| occupation | fishing, commercial, vigorous effort | 7 |

| occupation | forestry, ax chopping, very fast, 1.25 kg axe, 51 blows/min, extremely vigorous effort | 17.5 |

| occupation | forestry, ax chopping, slow, 1.25 kg axe, 19 blows/min, moderate effort | 5 |

| occupation | forestry, ax chopping, fast, 1.25 kg axe, 35 blows/min, vigorous effort | 8 |

| occupation | forestry, moderate effort (e.g., sawing wood with power saw, weeding, hoeing) | 4.5 |

| occupation | forestry, vigorous effort (e.g., barking, felling, or trimming trees, carrying or stacking logs, planting seeds, sawing lumber by hand) | 8 |

| occupation | furriery | 4.5 |

| occupation | garbage collector, walking, dumping bins into truck | 4 |

| occupation | hairstylist (e.g., plaiting hair, manicure, make-up artist) | 1.8 |

| occupation | horse grooming, including feeding, cleaning stalls, bathing, brushing, clipping, longeing and exercising horses | 7.3 |

| occupation | horse, feeding, watering, cleaning stalls, implied walking and lifting loads | 4.3 |

| occupation | horse racing, galloping | 7.3 |

| occupation | horse racing, trotting | 5.8 |

| occupation | horse racing, walking | 3.8 |

| occupation | kitchen maid | 3 |

| occupation | lawn keeper, yard work, general | 4 |

| occupation | laundry worker | 3.3 |

| occupation | locksmith | 3 |

| occupation | machine tooling (e.g., machining, working sheet metal, machine fitter, operating lathe, welding) light-to-moderate effort | 3 |

| occupation | Machine tooling, operating punch press, moderate effort | 5 |

| occupation | manager, property | 1.8 |

| occupation | manual or unskilled labor, general, light effort | 2.8 |

| occupation | manual or unskilled labor, general, moderate effort | 4.5 |

| occupation | manual or unskilled labor, general, vigorous effort | 6.5 |

| occupation | masonry, concrete, moderate effort | 4.3 |

| occupation | masonry, concrete, light effort | 2.5 |

| occupation | massage therapist, standing | 4 |

| occupation | moving, carrying or pushing heavy objects, 75 lbs or more, only active time (e.g., desks, moving van work) | 7.5 |

| occupation | skindiving or SCUBA diving as a frogman, Navy Seal | 12 |

| occupation | operating heavy duty equipment, automated, not driving | 2.5 |

| occupation | orange grove work, picking fruit | 4.5 |

| occupation | painting,house, furniture, moderate effort | 3.3 |

| occupation | plumbing activities | 3 |

| occupation | printing, paper industry worker, standing | 2 |

| occupation | police, directing traffic, standing | 2.5 |

| occupation | police, driving a squad car, sitting | 2.5 |

| occupation | police, riding in a squad car, sitting | 1.3 |

| occupation | police, making an arrest, standing | 4 |

| occupation | postal carrier, walking to deliver mail | 2.3 |

| occupation | shoe repair, general | 2 |

| occupation | shoveling, digging ditches | 7.8 |

| occupation | shoveling, more than 16 lbs/minute, deep digging, vigorous effort | 8.8 |

| occupation | shoveling, less than 10 lbs/minute, moderate effort | 5 |

| occupation | shoveling, 10 to 15 lbs/minute, vigorous effort | 6.5 |

| occupation | sitting tasks, light effort (e.g., office work, chemistry lab work, computer work, light assembly repair, watch repair, reading, desk work) | 1.5 |

| occupation | sitting meetings, light effort, general, and/or with talking involved (e.g., eating at a business meeting) | 1.5 |

| occupation | sitting tasks, moderate effort (e.g., pushing heavy levers, riding mower/forklift, crane operation) | 2.5 |

| occupation | sitting, teaching stretching or yoga, or light effort exercise class | 2.8 |

| occupation | standing tasks, light effort (e.g., bartending, store clerk, assembling, filing, duplicating, librarian, putting up a Christmas tree, standing and talking at work, changing clothes when teaching physical education, standing) | 3 |

| occupation | standing, light/moderate effort (e.g., assemble/repair heavy parts, welding,stocking parts,auto repair,standing, packing boxes, nursing patient care) | 3 |

| occupation | standing, moderate effort, lifting items continuously, 10 – 20 lbs, with limited walking or resting | 4.5 |

| occupation | standing, moderate effort, intermittent lifting 50 lbs, hitch/twisting ropes | 3.5 |

| occupation | standing, moderate/heavy tasks (e.g., lifting more than 50 lbs, masonry, painting, paper hanging) | 4.5 |

| occupation | steel mill, moderate effort (e.g., fettling, forging, tipping molds) | 5.3 |

| occupation | steel mill, vigorous effort (e.g., hand rolling, merchant mill rolling, removing slag, tending furnace) | 8.3 |

| occupation | tailoring, cutting fabric | 2.3 |

| occupation | tailoring, general | 2.5 |

| occupation | tailoring, hand sewing | 1.8 |

| occupation | tailoring, machine sewing | 2.5 |

| occupation | tailoring, pressing | 3.5 |

| occupation | tailoring, weaving, light effort (e.g., finishing operations, washing, dyeing, inspecting cloth, counting yards, paperwork) | 2 |

| occupation | tailoring, weaving, moderate effort (e.g., spinning and weaving operations, delivering boxes of yam to spinners, loading of warp bean, pinwinding, conewinding, warping, cloth cutting) | 4 |

| occupation | truck driving, loading and unloading truck, tying down load, standing, walking and carrying heavy loads | 6.5 |

| occupation | Truck, driving delivery truck, taxi, shuttlebus, school bus | 2 |

| occupation | typing, electric, manual or computer | 1.3 |

| occupation | using heavy power tools such as pneumatic tools (e.g., jackhammers, drills) | 6.3 |

| occupation | using heavy tools (not power) such as shovel, pick, tunnel bar, spade | 8 |

| occupation | walking on job, less than 2.0 mph, very slow speed, in office or lab area | 2 |

| occupation | walking on job, 3.0 mph, in office, moderate speed, not carrying anything | 3.5 |

| occupation | walking on job, 3.5 mph, in office, brisk speed, not carrying anything | 4.3 |

| occupation | walking on job, 2.5 mph, slow speed and carrying light objects less than 25 lbs | 3.5 |

| occupation | walking, gathering things at work, ready to leave | 3 |

| occupation | walking, 2.5 mph, slow speed, carrying heavy objects more than 25 lbs | 3.8 |

| occupation | walking, 3.0 mph, moderately and carrying light objects less than 25 lbs | 4.5 |

| occupation | walking, pushing a wheelchair | 3.5 |

| occupation | walking, 3.5 mph, briskly and carrying objects less than 25 lbs | 4.8 |

| occupation | walking or walk downstairs or standing, carrying objects about 25 to 49 lbs | 5 |

| occupation | walking or walk downstairs or standing, carrying objects about 50 to 74 lbs | 6.5 |

| occupation | walking or walk downstairs or standing, carrying objects about 75 to 99 lbs | 7.5 |

| occupation | walking or walk downstairs or standing, carrying objects about 100 lbs or more | 8.5 |

| occupation | working in scene shop, theater actor, backstage employee | 3 |

| religious activities | sitting in church, in service, attending a ceremony, sitting quietly | 1.3 |

| religious activities | sitting, playing an instrument at church | 2 |

| religious activities | sitting in church, talking or singing, attending a ceremony, sitting, active participation | 1.8 |

| religious activities | sitting, reading religious materials at home | 1.3 |

| religious activities | standing quietly in church, attending a ceremony | 1.3 |

| religious activities | standing, singing in church, attending a ceremony, standing, active participation | 2 |

| religious activities | kneeling in church or at home, praying | 1.3 |

| religious activities | standing, talking in church | 1.8 |

| religious activities | walking in church | 2 |

| religious activities | walking, less than 2.0 mph, very slow | 2 |

| religious activities | walking, 3.0 mph, moderate speed, not carrying anything | 3.5 |

| religious activities | walking, 3.5 mph, brisk speed, not carrying anything | 4.3 |

| religious activities | walk/stand combination for religious purposes, usher | 2 |

| religious activities | praise with dance or run, spiritual dancing in church | 5 |

| religious activities | serving food at church | 2.5 |

| religious activities | preparing food at church | 2 |

| religious activities | washing dishes, cleaning kitchen at church | 3.3 |

| religious activities | eating at church | 1.5 |

| religious activities | eating/talking at church or standing eating, American Indian Feast days | 2 |

| religious activities | cleaning church | 3.3 |

| religious activities | general yard work at church | 4 |

| religious activities | standing, moderate effort (e.g., lifting heavy objects, assembling at fast rate) | 3.5 |

| religious activities | Standing, moderate-to-heavy effort, manual labor, lifting 50 lbs, heavy maintenance | 4.5 |

| religious activities | typing, electric, manual, or computer | 1.3 |

| running | jog/walk combination (jogging component of less than 10 minutes) | 6 |

| running | jogging, general | 7 |

| running | jogging, in place | 8 |

| running | jogging, on a mini-tramp | 4.5 |

| running | Running, 4 mph (13 min/mile) | 6 |

| running | running, 5 mph (12 min/mile) | 8.3 |

| running | running, 5.2 mph (11.5 min/mile) | 9 |

| running | running, 6 mph (10 min/mile) | 9.8 |

| running | running, 6.7 mph (9 min/mile) | 10.5 |

| running | running, 7 mph (8.5 min/mile) | 11 |

| running | running, 7.5 mph (8 min/mile) | 11.5 |

| running | running, 8 mph (7.5 min/mile) | 11.8 |

| running | running, 8.6 mph (7 min/mile) | 12.3 |

| running | running, 9 mph (6.5 min/mile) | 12.8 |

| running | running, 10 mph (6 min/mile) | 14.5 |

| running | running, 11 mph (5.5 min/mile) | 16 |

| running | running, 12 mph (5 min/mile) | 19 |

| running | running, 13 mph (4.6 min/mile) | 19.8 |

| running | running, 14 mph (4.3 min/mile) | 23 |

| running | running, cross country | 9 |

| running | running | 8 |

| running | running, stairs, up | 15 |

| running | running, on a track, team practice | 10 |

| running | running, training, pushing a wheelchair or baby carrier | 8 |

| running | running, marathon | 13.3 |

| self care | getting ready for bed, general, standing | 2.3 |

| self care | sitting on toilet, eliminating while standing or squatting | 1.8 |

| self care | bathing, sitting | 1.5 |

| self care | dressing, undressing, standing or sitting | 2.5 |

| self care | eating, sitting | 1.5 |

| self care | talking and eating or eating only, standing | 2 |

| self care | taking medication, sitting or standing | 1.5 |

| self care | grooming, washing hands, shaving, brushing teeth, putting on make-up, sitting or standing | 2 |

| self care | hairstyling, standing | 2.5 |

| self care | having hair or nails done by someone else, sitting | 1.3 |

| self care | showering, toweling off, standing | 2 |

| sexual activity | active, vigorous effort | 2.8 |

| sexual activity | general, moderate effort | 1.8 |

| sexual activity | passive, light effort, kissing, hugging | 1.3 |

| sports | Alaska Native Games, Eskimo Olympics, general | 5.5 |

| sports | archery, non-hunting | 4.3 |

| sports | badminton, competitive | 7 |

| sports | badminton, social singles and doubles, general | 5.5 |

| sports | basketball, game | 8 |

| sports | basketball, non-game, general | 6 |

| sports | basketball, general | 6.5 |

| sports | basketball, officiating | 7 |

| sports | basketball, shooting baskets | 4.5 |

| sports | basketball, drills, practice | 9.3 |

| sports | basketball, wheelchair | 7.8 |

| sports | billiards | 2.5 |

| sports | bowling | 3 |

| sports | bowling, indoor, bowling alley | 3.8 |

| sports | boxing, in ring, general | 12.8 |

| sports | boxing, punching bag | 5.5 |

| sports | boxing, sparring | 7.8 |

| sports | broomball | 7 |

| sports | children’s games, adults playing (e.g., hopscotch, 4-square, dodgeball, playground apparatus, t-ball, tetherball, marbles, arcade games), moderate effort | 5.8 |

| sports | cheerleading, gymnastic moves, competitive | 6 |

| sports | coaching, football, soccer, basketball, baseball, swimming, etc. | 4 |

| sports | coaching, actively playing sport with players | 8 |

| sports | cricket, batting, bowling, fielding | 4.8 |

| sports | croquet | 3.3 |

| sports | curling | 4 |

| sports | darts, wall or lawn | 2.5 |

| sports | drag racing, pushing or driving a car | 6 |

| sports | auto racing, open wheel | 8.5 |

| sports | fencing | 6 |

| sports | football, competitive | 8 |

| sports | football, touch, flag, general | 8 |

| sports | football, touch, flag, light effort | 4 |

| sports | football or baseball, playing catch | 2.5 |

| sports | frisbee playing, general | 3 |

| sports | frisbee, ultimate | 8 |

| sports | golf, general | 4.8 |

| sports | golf, walking, carrying clubs | 4.3 |

| sports | golf, miniature, driving range | 3 |

| sports | golf, walking, pulling clubs | 5.3 |

| sports | golf, using power cart | 3.5 |

| sports | gymnastics, general | 3.8 |

| sports | hacky sack | 4 |

| sports | handball, general | 12 |

| sports | handball, team | 8 |

| sports | high ropes course, multiple elements | 4 |

| sports | hang gliding | 3.5 |

| sports | hockey, field | 7.8 |

| sports | hockey, ice, general | 8 |

| sports | hockey, ice, competitive | 10 |

| sports | horseback riding, general | 5.5 |

| sports | horse chores, feeding, watering, cleaning stalls, implied walking and lifting loads | 4.3 |

| sports | saddling, cleaning, grooming, harnessing and unharnessing horse | 4.5 |

| sports | horseback riding, trotting | 5.8 |

| sports | horseback riding, canter or gallop | 7.3 |

| sports | horseback riding,walking | 3.8 |

| sports | horseback riding, jumping | 9 |

| sports | horse cart, driving, standing or sitting | 1.8 |

| sports | horseshoe pitching, quoits | 3 |

| sports | jai alai | 12 |

| sports | martial arts, different types, slower pace, novice performers, practice | 5.3 |

| sports | martial arts, different types, moderate pace (e.g., judo, jujitsu, karate, kick boxing, tae kwan do, tai-bo, Muay Thai boxing) | 10.3 |

| sports | juggling | 4 |

| sports | kickball | 7 |

| sports | lacrosse | 8 |

| sports | lawn bowling, bocce ball, outdoor | 3.3 |

| sports | moto-cross, off-road motor sports, all-terrain vehicle, general | 4 |

| sports | orienteering | 9 |

| sports | paddleball, competitive | 10 |

| sports | paddleball, casual, general | 6 |

| sports | polo, on horseback | 8 |

| sports | racquetball, competitive | 10 |

| sports | racquetball, general | 7 |

| sports | rock or mountain climbing | 8 |

| sports | rock climbing, ascending rock, high difficulty | 7.5 |

| sports | rock climbing, ascending or traversing rock, low-to-moderate difficulty | 5.8 |

| sports | rock climbing, rappelling | 5 |

| sports | rodeo sports, general, light effort | 4 |

| sports | rodeo sports, general, moderate effort | 5.5 |

| sports | rodeo sports, general, vigorous effort | 7 |

| sports | rope jumping, fast pace, 120-160 skips/min | 12.3 |

| sports | rope jumping, moderate pace, 100-120 skips/min, general, 2 foot skip, plain bounce | 11.8 |

| sports | rope jumping, slow pace, < 100 skips/min, 2 foot skip, rhythm bounce | 8.8 |

| sports | rugby, union, team, competitive | 8.3 |

| sports | rugby, touch, non-competitive | 6.3 |

| sports | shuffleboard | 3 |

| sports | skateboarding, general, moderate effort | 5 |

| sports | skateboarding, competitive, vigorous effort | 6 |

| sports | skating, roller | 7 |

| sports | rollerblading, in-line skating, 14.4 km/h (9.0 mph), recreational pace | 7.5 |

| sports | rollerblading, in-line skating, 17.7 km/h (11.0 mph), moderate pace, exercise training | 9.8 |

| sports | rollerblading, in-line skating, 21.0 to 21.7 km/h (13.0 to 13.6 mph), fast pace, exercise training | 12.3 |

| sports | rollerblading, in-line skating, 24.0 km/h (15.0 mph), maximal effort | 14 |

| sports | skydiving, base jumping, bungee jumping | 3.5 |

| sports | soccer, competitive | 10 |

| sports | soccer, casual, general | 7 |

| sports | softball or baseball, fast or slow pitch, general | 5 |

| sports | softball, practice | 4 |

| sports | softball, officiating | 4 |

| sports | softball, pitching | 6 |

| sports | sports spectator, very excited, emotional, physically moving | 3.3 |

| sports | squash | 12 |

| sports | squash, general | 7.3 |

| sports | table tennis, ping pong | 4 |

| sports | tai chi, qi gong, general | 3 |

| sports | tai chi, qi gong, sitting, light effort | 1.5 |

| sports | tennis, general | 7.3 |

| sports | tennis, doubles | 6 |

| sports | tennis, doubles | 4.5 |

| sports | tennis, singles | 8 |

| sports | tennis, hitting balls, non-game play, moderate effort | 5 |

| sports | trampoline, recreational | 3.5 |

| sports | trampoline, competitive | 4.5 |

| sports | volleyball | 4 |

| sports | volleyball, competitive, in gymnasium | 6 |

| sports | volleyball, non-competitive, 6 – 9 member team, general | 3 |

| sports | volleyball, beach, in sand | 8 |

| sports | wrestling (one match = 5 minutes) | 6 |

| sports | wallyball, general | 7 |

| sports | track and field (e.g., shot, discus, hammer throw) | 4 |

| sports | track and field (e.g., high jump, long jump, triple jump, javelin, pole vault) | 6 |

| sports | track and field (e.g., steeplechase, hurdles) | 10 |

| transportation | automobile or light truck (not a semi) driving | 2.5 |

| transportation | riding in a car or truck | 1.3 |

| transportation | riding in a bus or train | 1.3 |

| transportation | flying airplane or helicopter | 1.8 |

| transportation | motor scooter, motorcycle | 3.5 |

| transportation | pulling rickshaw | 6.3 |

| transportation | pushing plane in and out of hangar | 6 |

| transportation | truck, semi, tractor, > 1 ton, or bus, driving | 2.5 |

| transportation | walking for transportation, 2.8-3.2 mph, level, moderate pace, firm surface | 3.5 |

| volunteer activities | sitting, meeting, general, and/or with talking involved | 1.5 |

| volunteer activities | sitting, light office work, in general | 1.5 |

| volunteer activities | sitting, moderate work | 2.5 |

| volunteer activities | standing, light work (filing, talking, assembling) | 2.3 |

| volunteer activities | sitting, child care, only active periods | 2 |

| volunteer activities | standing, child care, only active periods | 3 |

| volunteer activities | walk/run play with children, moderate, only active periods | 3.5 |

| volunteer activities | walk/run play with children, vigorous, only active periods | 5.8 |

| volunteer activities | standing, light/moderate work (e.g., pack boxes, assemble/repair, set up chairs/furniture) | 3 |

| volunteer activities | standing, moderate (lifting 50 lbs., assembling at fast rate) | 3.5 |

| volunteer activities | standing, moderate/heavy work | 4.5 |

| volunteer activities | typing, electric, manual, or computer | 1.3 |

| volunteer activities | walking, less than 2.0 mph, very slow | 2 |

| volunteer activities | walking, 3.0 mph, moderate speed, not carrying anything | 3.5 |

| volunteer activities | walking, 3.5 mph, brisk speed, not carrying anything | 4.3 |

| volunteer activities | walking, 2.5 mph slowly and carrying objects less than 25 lbs | 3.5 |

| volunteer activities | walking, 3.0 mph moderately and carrying objects less than 25 lbs, pushing something | 4.5 |

| volunteer activities | walking, 3.5 mph, briskly and carrying objects less than 25 lbs | 4.8 |

| volunteer activities | walk/stand combination, for volunteer purposes | 3 |

| walking | backpacking | 7 |

| walking | backpacking, hiking or organized walking with a daypack | 7.8 |

| walking | carrying 15 pound load (e.g. suitcase), level ground or downstairs | 5 |

| walking | carrying 15 lb child, slow walking | 2.3 |

| walking | carrying load upstairs, general | 8.3 |

| walking | carrying 1 to 15 lb load, upstairs | 5 |

| walking | carrying 16 to 24 lb load, upstairs | 6 |

| walking | carrying 25 to 49 lb load, upstairs | 8 |

| walking | carrying 50 to 74 lb load, upstairs | 10 |

| walking | carrying > 74 lb load, upstairs | 12 |

| walking | loading /unloading a car, implied walking | 3.5 |

| walking | climbing hills, no load | 6.3 |

| walking | climbing hills with 0 to 9 lb load | 6.5 |

| walking | climbing hills with 10 to 20 lb load | 7.3 |

| walking | climbing hills with 21 to 42 lb load | 8.3 |

| walking | climbing hills with 42+ lb load | 9 |

| walking | descending stairs | 3.5 |

| walking | hiking, cross country | 6 |

| walking | hiking or walking at a normal pace through fields and hillsides | 5.3 |

| walking | bird watching, slow walk | 2.5 |

| walking | marching, moderate speed, military, no pack | 4.5 |

| walking | marching rapidly, military, no pack | 8 |

| walking | pushing or pulling stroller with child or walking with children, 2.5 to 3.1 mph | 4 |

| walking | pushing a wheelchair, non-occupational | 3.8 |

| walking | race walking | 6.5 |

| walking | stair climbing, using or climbing up ladder | 8 |

| walking | stair climbing, slow pace | 4 |

| walking | stair climbing, fast pace | 8.8 |

| walking | using crutches | 5 |

| walking | walking, household | 2 |

| walking | walking, less than 2.0 mph, level, strolling, very slow | 2 |

| walking | walking, 2.0 mph, level, slow pace, firm surface | 2.8 |

| walking | walking for pleasure | 3.5 |

| walking | walking from house to car or bus, from car or bus to go places, from car or bus to and from the worksite | 2.5 |

| walking | walking to neighbor’s house or family’s house for social reasons | 2.5 |

| walking | walking the dog | 3 |

| walking | walking, 2.5 mph, level, firm surface | 3 |

| walking | walking, 2.5 mph, downhill | 3.3 |

| walking | walking, 2.8 to 3.2 mph, level, moderate pace, firm surface | 3.5 |

| walking | walking, 3.5 mph, level, brisk, firm surface, walking for exercise | 4.3 |

| walking | walking, 2.9 to 3.5 mph, uphill, 1 to 5% grade | 5.3 |

| walking | walking, 2.9 to 3.5 mph, uphill, 6% to 15% grade | 8 |

| walking | walking, 4.0 mph, level, firm surface, very brisk pace | 5 |

| walking | walking, 4.5 mph, level, firm surface, very, very brisk | 7 |

| walking | walking, 5.0 mph, level, firm surface | 8.3 |

| walking | walking, 5.0 mph, uphill, 3% grade | 9.8 |

| walking | walking, for pleasure, work break | 3.5 |

| walking | walking, grass track | 4.8 |

| walking | walking, normal pace, plowed field or sand | 4.5 |

| walking | walking, to work or class | 4 |

| walking | walking, to and from an outhouse | 2.5 |

| walking | walking, for exercise, 3.5 to 4 mph, with ski poles, Nordic walking, level, moderate pace | 4.8 |

| walking | walking, for exercise, 5.0 mph, with ski poles, Nordic walking, level, fast pace | 9.5 |

| walking | walking, for exercise, with ski poles, Nordic walking, uphill | 6.8 |

| walking | walking, backwards, 3.5 mph, level | 6 |

| walking | walking, backwards, 3.5 mph, uphill, 5% grade | 8 |

| water activities | boating, power, driving | 2.5 |

| water activities | boating, power, passenger, light | 1.3 |

| water activities | canoeing, on camping trip | 4 |

| water activities | canoeing, harvesting wild rice, knocking rice off the stalks | 3.3 |

| water activities | canoeing, portaging | 7 |

| water activities | canoeing, rowing, 2.0-3.9 mph, light effort | 2.8 |

| water activities | canoeing, rowing, 4.0-5.9 mph, moderate effort | 5.8 |

| water activities | canoeing, rowing, kayaking, competition, >6 mph, vigorous effort | 12.5 |

| water activities | canoeing, rowing, for pleasure, general | 3.5 |

| water activities | canoeing, rowing, in competition, or crew or sculling | 12 |

| water activities | diving, springboard or platform | 3 |

| water activities | kayaking, moderate effort | 5 |

| water activities | paddle boat | 4 |

| water activities | sailing, boat and board sailing, windsurfing, ice sailing, general | 3 |

| water activities | sailing, in competition | 4.5 |

| water activities | sailing, Sunfish/Laser/Hobby Cat, Keel boats, ocean sailing, yachting, leisure | 3.3 |

| water activities | skiing, water or wakeboarding | 6 |

| water activities | jet skiing, driving, in water | 7 |

| water activities | skindiving, fast | 15.8 |

| water activities | skindiving, moderate | 11.8 |

| water activities | skindiving, scuba diving, general | 7 |

| water activities | snorkeling | 5 |

| water activities | surfing, body or board, general | 3 |

| water activities | surfing, body or board, competitive | 5 |

| water activities | paddle boarding, standing | 6 |

| water activities | swimming laps, freestyle, fast, vigorous effort | 9.8 |

| water activities | swimming laps, freestyle, front crawl, slow, light or moderate effort | 5.8 |

| water activities | swimming, backstroke, general, training or competition | 9.5 |

| water activities | swimming, backstroke, recreational | 4.8 |

| water activities | swimming, breaststroke, general, training or competition | 10.3 |

| water activities | swimming, breaststroke, recreational | 5.3 |

| water activities | swimming, butterfly, general | 13.8 |

| water activities | swimming, crawl, fast speed, ~75 yards/minute, vigorous effort | 10 |

| water activities | swimming, crawl, medium speed, ~50 yards/minute, vigorous effort | 8.3 |

| water activities | swimming, lake, ocean, river | 6 |

| water activities | swimming, leisurely, not lap swimming, general | 6 |

| water activities | swimming, sidestroke, general | 7 |

| water activities | swimming, synchronized | 8 |

| water activities | swimming, treading water, fast, vigorous effort | 9.8 |

| water activities | swimming, treading water, moderate effort, general | 3.5 |

| water activities | tubing, floating on a river, general | 2.3 |

| water activities | water aerobics, water calisthenics | 5.5 |

| water activities | water polo | 10 |

| water activities | water volleyball | 3 |

| water activities | water jogging | 9.8 |

| water activities | water walking, light effort, slow pace | 2.5 |

| water activities | water walking, moderate effort, moderate pace | 4.5 |

| water activities | water walking, vigorous effort, brisk pace | 6.8 |

| water activities | whitewater rafting, kayaking, or canoeing | 5 |

| water activities | windsurfing, not pumping for speed | 5 |

| water activities | windsurfing or kitesurfing, crossing trial | 11 |

| water activities | windsurfing, competition, pumping for speed | 13.5 |

| winter activities | dog sledding, mushing | 7.5 |

| winter activities | dog sledding, passenger | 2.5 |

| winter activities | moving ice house, set up/drill holes | 6 |

| winter activities | ice fishing, sitting | 2 |

| winter activities | skating, ice dancing | 14 |

| winter activities | skating, ice, 9 mph or less | 5.5 |

| winter activities | skating, ice, general | 7 |

| winter activities | skating, ice, rapidly, more than 9 mph, not competitive | 9 |

| winter activities | skating, speed, competitive | 13.3 |

| winter activities | ski jumping, climb up carrying skis | 7 |

| winter activities | skiing, general | 7 |

| winter activities | skiing, cross country, 2.5 mph, slow or light effort, ski walking | 6.8 |

| winter activities | skiing, cross country, 4.0-4.9 mph, moderate speed and effort, general | 9 |

| winter activities | skiing, cross country, 5.0-7.9 mph, brisk speed, vigorous effort | 12.5 |

| winter activities | skiing, cross country, >8.0 mph, elite skier, racing | 15 |

| winter activities | skiing, cross country, hard snow, uphill, maximum, snow mountaineering | 15.5 |

| winter activities | skiing, cross-country, skating | 13.3 |

| winter activities | skiing, cross-country, biathlon, skating technique | 13.5 |

| winter activities | skiing, downhill, alpine or snowboarding, light effort, active time only | 4.3 |

| winter activities | skiing, downhill, alpine or snowboarding, moderate effort, general, active time only | 5.3 |

| winter activities | skiing, downhill, vigorous effort, racing | 8 |

| winter activities | skiing, roller, elite racers | 12.5 |

| winter activities | sledding, tobogganing, bobsledding, luge | 7 |

| winter activities | snow shoeing, moderate effort | 5.3 |

| winter activities | snow shoeing, vigorous effort | 10 |

| winter activities | snowmobiling, driving, moderate | 3.5 |

| winter activities | snowmobiling, passenger | 2 |

| winter activities | snow shoveling, by hand, moderate effort | 5.3 |

| winter activities | snow shoveling, by hand, vigorous effort | 7.5 |

| winter activities | snow blower, walking and pushing | 2.5 |

Let’s take a look at what Dr. Attia has to say about Zone 2 and VO2 max training.

Zone 2 Training Builds A Strong Aerobic Baseline

Zone 2 is steady-state aerobics. A good way to know if you’re in Zone 2 is when you can still have a conversation despite the effort you’re producing, but you rather not, as opposed to anaerobic training where you can only muster short exclamations.

Zone 2 can be easy to do, even for someone who has been sedentary for a while, because, as mentioned by the talk test, it’s subjective. For some people, a brisk walk might get them into Zone 2; for those in better condition, Zone 2 necessitates walking uphill. Common Zone 2 training includes riding a stationary bike, or using an elliptical machine, or jogging.

In technical terms, Zone 2 is the maximum level of effort you can maintain without accumulating lactate. You will still produce lactate, but you’ll be able to match its production with its clearance. The more efficient your mitochondrial “engine,” the more rapidly you can clear lactate, and the greater effort you can sustain while remaining in Zone 2. (More about mitochondria here.) If you are “feeling the burn” in this type of workout, then we are likely going too hard, creating more lactate than we can eliminate.

In Outlive, Dr. Attia writes about San Millán, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, who has conducted some valuable research about why healthy mitochondria is the key to athletic performance and metabolic health.

Mitochondria can convert both glucose and fatty acids to energy. This is special, because although glucose can be metabolized in different ways, fatty acids can only be converted to energy in the mitochondria. You want healthy mitochondria (mitochondrial biogenesis) for many reasons, one being to achieve “metabolic flexibility”.

Metabolic flexibility refers to the ability to use both fuels, fat and glucose, to produce energy for the body. Typically, someone working at a lower relative intensity (Zone 2/aerobics) will be burning more fat, while at higher intensities (VO2 max/anaerobics) they would rely more on glucose. The healthier and more efficient your mitochondria, the greater will be your ability to utilize fat — by far the body’s most efficient and abundant fuel source.

San Millán believes that metabolic flexibility is fundamental for athletes, but even more important for nonathletes, because:

- It builds a base of endurance for your life’s activities — riding your bike for miles, or playing with your kids, grandkids, or great-grandkids.

- It plays a crucial role in preventing chronic disease by improving the health and efficiency of your mitochondria,

Mitochondria are very plastic, meaning they can undergo morphological and functional changes in response to cellular demands. When you do aerobic exercise, many new and more efficient mitochondria are created through a process called mitochondrial biogenesis. At the same time, dysfunctional mitochondria get recycled via a process called mitophagy (which is like autophagy, but specific to mitochondria).

A person who exercises frequently in Zone 2 improves their mitochondria at each exercise session. The converse is true as well — non-exercisers lose mitochondrial health. Inevitably, Zone 2 training builds muscle, a strong mediator of metabolic health and glucose homeostasis.

Muscle is our body’s largest glycogen storage sink in the body. When you create more mitochondria, you substantially augment your capacity for using that stored fuel, rather than having it end up as fat or remaining in blood plasma. You don’t want glucose to remain in your bloodstream. Chronic blood glucose elevations damage our heart, brain, kidneys and many other organs. It also contributes to erectile dysfunction in men.

Attia asserts that while we are exercising our overall glucose uptake increases as much as one-hundred-fold over what happens while at rest. During exercise, the glucose uptake occurs via multiple pathways — the usual insulin-signaled path, as well as one called non-insulin-mediated glucose uptake (NIMGU), where glucose is transported directly across the cell membrane without the involvement of insulin. This explains why exercise, particularly in Zone 2, can be so effective in ameliorating both type 1 and type 2 diabetes:

“It enables the body to essentially bypass insulin resistance in the muscles to draw down blood glucose levels”.

OK, not that you’ve laced up your sneakers for some Zone 2 training, let me convey what Attia says about the equally important part of cardiorespiratory fitness — Vo2 Max

VO2 max Training Builds Capacity

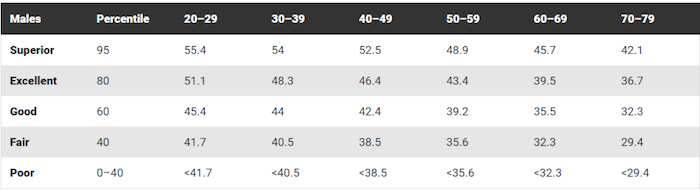

VO2 max, is a strong contender for the single most powerful marker for longevity. Typically expressed in terms of the volume of oxygen a person can use, per kilogram of body weight, per minute, VO2 max represents the maximum rate at which a person can utilize oxygen.

Whereas high intensity interval training (HIIT) intervals are very short, typically measured in seconds, or under two minutes, VO2 max intervals are a bit longer, ranging from three to eight minutes (but usually four is the most) — and are a bit less intense. You can do this type of training by running, on a bike, on a stationary bike, treadmill, rowing machine, or an “assault” bike (my favorite).

One effective formula for these VO2 max intervals is to go four minutes at the maximum pace you can sustain for, say, four minutes (a hard but less than exhaustive effort), and then bring the pace down for an easy four minute recovery period until the next interval.

Do not do VO2 max training until you have built a solid Zone 2 foundation!

Here’s some stats to consider showing the value of improving your VO2 max:

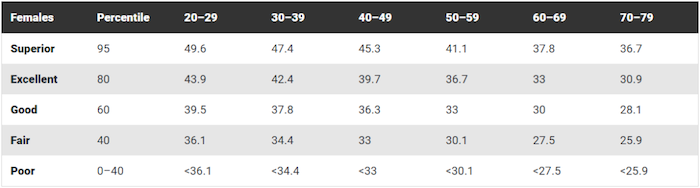

✔ Those below average VO2 Max (between 25th and 50th percentile) are at double the risk of all-cause mortality compared to those who are in the top quartile (75th to 97.6%). Given that a smoker has a 40% greater risk of all-cause mortality (risk of dying at any moment), poor cardiorespiratory fitness carries a greater relative risk than smoking!