Dr. Attia’s Outlive Book Review: Nutrition, Sleep and Emotions, Part 3

Dr. Attia’s Outlive book will help get your nutrition, sleep and emotional/psychological house in order. This is of paramount importance if you’re to live a long and healthy life, free of disease and anguish. Let Dr. Attia be your guide.

This is Part 3 of my three-part review of Longevity expert Dr. Peter Attia recently released book, Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity. Together, this three-part review will give you a lot of much-needed information about how to map your journey to a long and hale life; however, as I’ve emphasized in Part 1 and Part 2, I’m just giving you a taste of all the pearls the book offers.

If you’re interested in living long and strong, as we like to say around here, read the Outlive book.

In this post, Part 3, I will cover Attia’s perspectives on nutrition, sleep and emotions. In Part 1, I covered the Four Horsemen of disease, and in Part 2 I covered the best exercises to live longer include stability/mobility, cardiorespiratory and strength training.

Let’s dig in…

Nutrition: Less is More

Dr Attia is clearly flummoxed by this topic of nutrition and diet. It’s not that he doesn’t understand the science, but that he feels there’s so much conflicting information swarming around the subject of nutrition that it becomes difficult to find a balanced and defensible position about what food matters for healthspan and longevity.

Let’s break his two chapters about nutrition into the following segments:

- The problem with modern nutrition;

- The problem with nutritional studies; and

- The not-SAD Solution

The Problem with Nutrition Today

The fundamental problem with nutrition these days is that it’s nearly the opposite of how humans evolved back in the old days when we were hunters and gatherers. For the first time in human history, too many of us have too many calories available to consume too much of the time. This is not how humans evolved. Evolution did not prepare us for this ever-present food abundance. We evolved as hunters and gatherers, which necessitated moving our bodies and working together to gather and hunt food. Food was not always available, so we had to be able to survive long periods of food insufficiency. This is no longer the case. Now most of us are overnourished; meaning that we hold on to excess energy storage (body fat) that we do not need to use, because food is always available.

Not only is food abundant and available to so many of us, but its quality is, well, SAD. SAD stands for

“Standard American Diet” (unfortunately, no longer contained within America’s borders), and it disrupts the body’s metabolic equilibrium. SAD strains our body’s ability to control blood glucose levels, and causes us to store fat when it should be utilized for energy.

The leading source of SAD calories — our #1 food group in terms of calories — is a category referred to as “grain-based desserts” like pies, cakes and cookies, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

You don’t have to be a doctor or scientist to know that our diets are crap and are largely the cause of many of the chronic diseases rampant in society. The connection between disease, aging and diet has been, and continues to be studied extensively, and yet confusion abounds.

The Problem with Nutritional Studies

In his Outlive book, Attia maintains that diet nutrition is poorly understood by science, is emotionally loaded, and the subject is muddled by lousy information and lazy thinking. He doesn’t think about nutrition and diet in absolute terms; rather, that there’s a lot of nuance, especially because there’s a lot of variability given a person’s genetic makeup.

Part of the problem, says Attia, is many of the studies that try to determine what is the ideal diet — whether they be high fat or low fat high, carb low carb, etc. — are based on questionnaires or are poorly constructed in various ways, such as being composed of small numbers of participants studied over short periods of time. Unlike with, say, rats, you can’t put humans in a cage for their lifetime and feed them specific quantities of certain foods and come up with some unassailable tenants about nutrition.

Attia spends quite a bit of time explaining how nutritional studies can be inadequate in showing any causality between something eaten and some result based upon what was eaten. Most nutrition studies with humans make associations, or correlations, which can be affected by “user bias”. This means that the results of human nutritional studies often reflect the baseline health of the subjects more than the influence of whatever is being studied. A classic example of this are the many studies that correlate moderate alcohol consumption with improved health outcomes.

Attia says that such alcohol studies are tainted by healthy user bias, which in this case would refer to the fact that people who are still drinking in older age tend to do so because they are healthy and not the other way around. Similarly, people who drink zero alcohol often have some health-related reason to abstain, or an addiction-related reason for avoiding it. Attia cites a study published in JAMA (The Journal of the American Medical Association) that found that once you move the effects of confounding factors that accompany moderate drinking, such as lower BMI, affluence and not smoking, then any observed benefit of alcohol consumption completely disappears.

In his Outlive book, Attia describes what he says is a well-designed nutritional study with a clear and defensible result: a large Spanish study known as PREDIMED. This study examined 7,500 subjects, and rather than telling them what to eat, the researcher gave:

- A liter of olive oil each week to one group that participants would use to incentivize desired dietary changes, using the olive oil to eat foods that accompany olive oil.

- A quantity of nuts was given to a second group, who was told to eat one ounce of them per day.

- The third group (the control) was told to eat a lower fat diet with no nuts, no excess fat on the meat they ate, and for some reason, no fish.

This study was intended to last for six years but it was halted prematurely after just four and one-half years because of the dramatic results:

The olive oil group (group one) had about one-third lower incidents (31 percent) of stroke, heart attack and death than the low fat group (control), and group two given the nuts showed a reduced risk of 28 percent. it was, therefore, deemed unethical to continue the low-fat control group, and the trial was stopped. Given the reduced incidence of strokes, heart attacks and death, the nuts-or-olive-oil “Mediterranean” diet appeared to be as powerful as statins for primary prevention of heart disease, Attia concludes.

It should be noted that the PREDIMED subjects already had at least three serious risk factors such as type 2 diabetes, smoking, hypertension, elevated LG L-C, low HDL-C overweight or obesity or a family history of premature coronary heart disease. Yet, despite all these elevated risk factors, the olive oil or nuts diet helped them delay disease and death. A review of the data also found cognitive improvement in those allocated the Mediterranean-style diet versus cognitive decline in those allocated to the low fat diet control group.

The not-SAD Solution

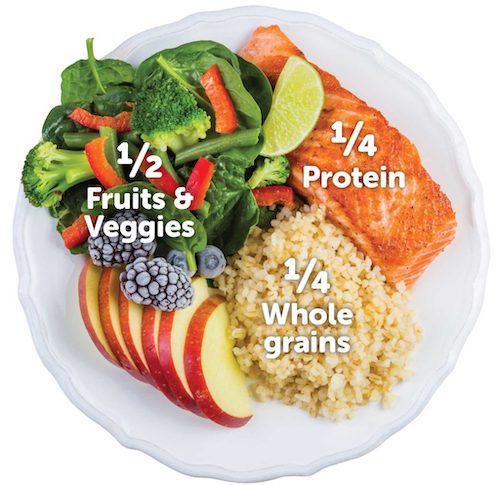

There are a plethora of different dietary or nutritional modalities to address SAD, such as:

- Caloric restriction — eating less in total, but without attention to what’s being eaten.

- Dietary restriction — eating less of some particular foods within the diet, like less meat, sugar or fats.

- Time restriction eating — restricting eating to certain times, including multi-day fasting.

Each of these has pros and cons, observes Attia.

Caloric restriction is the most time-tested dietary method for losing body fat and improving healthspan and longevity in humans (suggested) and other animals tested (proven). Although very efficacious, the problem with caloric restriction is compliance — we simply find it hard to go through life eating 20 percent or less than what we want.

Dietary restriction is a promising strategy that is conceptually simple: you pick a type of food that you don’t want to eat, and you don’t eat it. Assuming that food you select to eliminate is significant — meaning it has contributed to your poor diet, or your unhealthy body fat, then this is useful, if you can stick to it. The eliminated foods also need to put you in a caloric deficit, if the intent is to lose weight.

Time restriction eating is trendy, perhaps because many people who try it find that they can adhere to it, because you don’t have to think about anything other than the time frame within which you eat. One major problem with this approach is if your eating window is too short, you won’t be able to eat enough protein, leading to protein deficiency. Why? Because you can not synthesize more than approximately 35 to 45 grams of protein at once; thus, if for instance you ate just one meal a day, you would not be able to utilize your daily protein requirement, which exceeds 45 grams. (More on that later.)

Note that the common denominator in each of the above cited nutritional modalities is caloric deficit. Calories matter a lot. If you take in more calories than you expend on a consistent basis, many unhealthy things are awaiting you downstream. Surplus calories end up in our adipose tissue (body fat), and if we exceed the so-called safe capacity of our subcutaneous fat tissue, the excess fat goes into the liver, the viscera (organs in the cavities of the body) and the muscles.

Chronically consumed excess calories can result in many chronic diseases, not only metabolic disorders, but also heart disease, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease. The opposite is true, in that caloric restriction is known to improve health outcomes and even lifespan, at least in animals that have been tested, from worms to monkeys.

Even though you can’t put humans in the cage for the whole lifetime, scientists do that with various animals to test the effects of caloric restriction, typically feeding one group a restricted calorie diet, and letting the other group eat as much as they want (ad libitum).

In his Outlive book, Attia recounts a well-documented story about the two definitive studies that looked at the effects of caloric restriction on Rhesus monkeys that came out with different results: one study showed that caloric restriction led to longevity and better health, and the other one did not. When those two studies were examined side-by-side, the opposing outcomes emanated from the relative healthiness of the foods the monkey’s ate. The study in which the monkeys derived little benefit from caloric restriction ate food that contained 28.4 percent sucrose by weight; whereas, the study wherein the caloric restricted monkeys enjoyed life extension and health benefits were fed healthy food. The moral of this story is that the quality of food you eat matters — SAD is not good for monkeys, nor you.

Attia’s take away from these two monkey studies is as follows:

- Avoiding diabetes and related metabolic dysfunction, especially by eliminating or reducing junk food, is very important to longevity.

- There appears to be a strong link between calories and cancer, the leading cause of death in the control monkeys in both studies. The caloric restriction monkeys had a 50 percent lower incidence of cancer.

- The quality of the food consumed is as important as the quantity. Eat much less of SAD.

- If your diet is high quality (see my post about that) and you’re metabolically healthy (see Part 2 and this post), then only a small reduction in calories is beneficial to healthy longevity.

Attia covers much more about nutrition in his book, Outlive, particularly as it pertains to the three macronutrients — carbohydrates, proteins and fats — as well as a fourth macronutrient he adds to the list, alcohol. Attia thinks that alcohol should be considered as its own category of macronutrient because it’s so widely consumed, has such a strong effect on metabolism, and that at seven calories per gram, is calorically dense (fat is at nine, and carbs and protein are at four calories per gram). As I keep repeating, I recommend you read Attia’s Outlive book.

Sleep: More is Good

Dr. Attia begins his Outlive chapter on sleep by recounting all the different ways he was a knucklehead during his medical school years, and a few thereafter, when he would push himself at his work with very little sleep, in keeping with that old bromide, I’ll sleep when I’m dead. It took him a decade or so after medical school when he finally realized that he’d be dead earlier if he didn’t get some sleep.

I’m going to quickly summarize the health impacts of insufficient and restorative sleep, describe the different stages of sleep, and then finally summarize what Peter has to say you can do to improve sleep.

- The impact of sleep on health

- The stages of sleep

- How to improve your sleep

The Impact of Sleep on Health

Researchers report that people who are sleep deprived almost always underestimate its effects on them because they adapt to it. And with that adaptation comes a disconnection between how they might be performing come or lack thereof, due to impaired sleep. This lack of awareness is called baseline resetting.

Here’s a very brief list of problems that can occur if you get too little sleep too much of the time:

- Your skin looks older than that of people at the same age who sleep more.

- Your metabolism gets wrecked. Even short-term sleep deprivation can cause insulin resistance.

- Risk associations have been found between poor or short sleep and hypertension at 17 percent (greater risk), cardiovascular disease at 16 percent, coronary disease at 26 percent, and obesity 38 percent.

- Chronic sleep deprivation can lead to Alzheimer’s and dementia.

There is an amplifying, circular effect between stress and poor sleep, in that higher stress levels can make us sleep poorly, and poor sleep also makes us more stressed. Poor sleep and high stress activate the sympathetic nervous system, which is part of our fight or flight response. This promotes the release of hormones called glucose corticoids, including this stress hormone cortisol.

Cortisol raises blood pressure, and it causes glucose to be released from the liver, while inhibiting the uptake and utilization of glucose in muscle and fat tissues, perhaps in order to prioritize glucose delivery to the brain. This winds up manifesting as elevated glucose due to stress-induced insulin resistance.

Suppression of leptin, the hormone that signals that we are fed, also can occur with insufficient sleep, and that leads to increased levels of ghrelin, the hunger hormone. So, less sleep, more eating.

Now let’s turn to the different stages of sleep.

The Stages of Sleep

In his Outlive book, Dr. Attia reviews the series of well-defined stages of sleep, each of which has a specific function and a specific electrical brain wave signature, which is how researchers have been able to identify these distinctly different sleep stages.

Typically, after we fall asleep, we quickly pass through a period of light sleep before dropping into deep sleep. This sleep stage is called non-rem or NREM (REM meaning rapid eye movement), and it comes in two strengths, light-NREM and deep-NREM, the latter being more important.

Most of our dreaming occurs during REM sleep. In this sleep state, our mind is processing images and events that seem familiar, but are also strange or dislocated from their typical context. The electrical signature of REM sleep is similar to when we’re awake, the main difference being that our body seems paralyzed.

Both REM and deep NREM sleep are crucial to learning and memory, but for different reasons. Deep sleep enables the brain to, in effect, clear out its cache of short-term memories in the hippocampus, and selects the important memories for long-term storage in the cortex, thus helping us to store and reinforce our most important memories of the day. Researchers have observed a direct relationship between how much deep sleep we get in a given night and how well we perform on a memory test the next day.

Young people spend more time in REM, and plateaus in adulthood, although still remains important for creativity and problem solving. REM sleep is especially helpful for procedural memory, which is learning new ways of moving the body for athletes and musicians. REM sleep is also important for us to process our emotional memories, helping separate our emotions from the memory of the negative or positive experience that triggered those emotions. This is why if we go to bed upset about something, we tend to wake up in the morning feeling better.

There’s an emotional component to REM as well, as this stage of sleep helps us maintain our emotional awareness. Studies have shown that when deprived of REM sleep, we have a more difficult time reading facial expressions. This is important, because our ability to function as the social animals that we are depends on the ability to understand and navigate the feelings of others.

Deep sleep is essential to the very health of our brain as an organ. When in deep sleep, the brain activates a sort of internal waste disposal system that allows cerebrospinal fluid to flow in between neurons and “sweep away” intercellular junk. Collectively this cleansing process flushes out detritus and cleanses both amyloid beta and tau, the two proteins linked to neurodegeneration. Those who commonly sleep less than seven hours per night over decades tend to have more amyloid beta and TAU build-up in their brains than those who sleep seven plus more hours per night.

Unfortunately, insomnia affects 30 to 50 percent of older adults. Research shows sleep disturbances often precede the diagnosis of dementia by several years. The converse is true — superior sleep quality in older adults is associated with lower risk of developing cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, achieving successful sleep patterns may delay the age of onset into cognitive impairment by as much as 11 years, and may improve cognitive function in patients already diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

How To Improve Your Sleep

The first thing you have to do, says Attia, is to overcome the predilection for baseline resetting so that you can objectively assess the quality of your sleep. If you find that it’s compromised, you need to act to get restorative sleep on a regular basis.

In Outlive, Attia reviews a few sleep-inducing pharmaceuticals, each having a different downside that have to do with things such as impairing the normal levels of the different stages of sleep. He encourages people who are dependent upon using drugs to induce sleep to wean off them.

He has found that there is no magic bullet for sleep, but in his clinical practice he has found that his patient’s typically do better with an old anti-depressant called trazodone, at low dosages, from 100 to 50 milligrams, or even less, depending on the individual. He also says that he’s also had positive results with the herbal supplement ashwagandha.

Attia cautions, however, that none of this is going to be effective if you have a true sleep disorder such as insomnia or sleep apnea.

To assess your own sleep habits, Attia mentions that there are numerous sleep tracking devices that can be helpful. They work by measuring variables such as heart rate, heart rate variability, movement breathing rate, etc. Various watches track sleep quality, such as those made by Apple, Google and Garmin.

And now to the last part of Attia’s Outlive book, emotions.

Emotions: Mindfulness is Key

Up until this point, I have focused almost entirely on the physical aspects of healthspan and longevity in this post, and in Part 1 and 2, but here I will briefly explore their emotional and mental sides, which in some ways, Attia asserts, are more important than everything else that I’ve laid out thus far.

I’ll tell you straight up that I will not even try to do justice to Attia’s story about how he came to understand the importance of emotional and psychological stability, for this is a deeply personal story that he relates, and it’s his to tell, not mine. However, I will provide a few highlights to give you the gist of what we wrote.

In his Outlive book, Attia exposes the high price he paid for ignoring his emotional health for decades, as he disassembles his journey to mental and emotional wellness. He discovered that emotional health and physical health are closely intertwined.

Feeling connected and having healthy, intimate relationships with others and with oneself is imperative to maintaining efficient glucose metabolism or an optimal lipoprotein profile, not to mention simply feeling happy.

Dealing with emotional health for some people might be more difficult than with physical health because oftentimes people slowly slide down into emotional dysfunction and are unaware of the need to make changes.

Addressing emotional health takes as much effort and daily practice as is afforded physical health, something that was totally ignored by Attia. He relentlessly applied himself to honing his physical capabilities while ignoring the growing psycho-emotional embers deep within him that would soon erupt into a bonfire, nearly consuming him.

Attia got a lot of help to get his emotional/psychological house in order. He had to learn to reframe — the ability to look at a given situation from someone else’s point of view, which for him (and most people) a very difficult thing to do. He had to learn to execute concrete skills repetitively under stress that aim to break the chain reaction of negative thoughts that lead to negative emotion that lead to negative thoughts that lead to negative actions. To break this chain reaction, Attia had to remain vigilantly mindful of his thoughts, emotions and attitudes.

Through extensive therapy, Attia came to accept that he had built a “structure of perfectionism and workaholism on the pillars of performance-based esteem.” The structure was built on a foundation of shame, some brought on by trauma and some of which was inherited as children take on the shame of those around them.

I will end this review of Outlive as did Peter and his book, where he quotes Paulo Coelho, the Brazilian lyricist and novelist:

“Maybe the journey isn’t so much about becoming anything. Maybe it’s about becoming everything that isn’t really you, so you can be who you were meant to be in the first place”

Subscribe to my Newsletter!

Last Updated on July 22, 2023 by Joe Garma