Stop Counting Calories to Lose Weight. Do This Instead.

Stop counting calories to lose weight is good advice if you actually want to lose weight and gain health. The bottom line is that counting calories rarely works in the long-run. Two other methods will work better.

Stop counting calories to lose weight is the basic conclusion made by a review and meta-analysis examining 80 weight loss clinical trials. The researchers compared different methods of dieting, including low-calorie diets.

Their findings:

A diet focused on drastically reducing caloric intake initially produces dramatic weight loss. But people’s weight steadily rises back.

How steady is that regaining of the weight lost?

Let’s put it this way: at the three-year mark, most people — around 80% — rapidly approach their starting weight; so, you nearly go full circle within three years.

Keep reading and learn why it’s a good idea to stop counting calories to lose weight, and what to do instead.

Here’s what I cover in this post:

Let’s dive in…

Why Counting Calories Doesn’t Work

Accurately counting calories doesn’t work as a fat-loss strategy because of issues concerning absorption, food structure, and the food matrix.

Let’s look at each of those, but first…

What’s a calorie?

One calorie is the amount of energy it takes to warm up 1 kilogram of water from 0°C (32 °F) to 1°C (33.8 °F).

Different macronutrients have varying amounts of energy. Roughly speaking, it goes like this:

- 1 gram of carbohydrate provides 4 calories

- 1 g of protein provides 4 calories

- 1 g of fat provides 9 calories

However, these are averages, and those numbers don’t always bear out at the dinner table. The calories listed on a food label is really only an estimate — amounts can vary.

Food manufacturers food labels can legally be inaccurate up to 20% of their estimates. That means a “100-calorie” snack might contain anything from 80 to 120 calories.

Plus, portion sizes are impossible to control accurately. Restaurant estimates of calories can vary by more than 50%.

Then there’s the impact of cooking, which many food labels don’t take into account. The caloric content of food can be hugely affected by cooking. For instance, a raw stick of celery has six calories, but it has six times that — 36 calories — when cooked.

Now, let’s look at another problem with calorie counting…

Absorption is key

Along with the fact that you can’t be 100% confident about how many calories you’ve eaten, there’s also the problem with absorption — the number of calories in your meal that get absorbed.

When food is absorbed, it means that the body has broken down the large molecules of food into smaller molecules and absorbed them through the walls of the small intestine into the bloodstream. These nutrients are then delivered to other parts of the body to store or use.

The problem is that even if you knew exactly how many calories were in your meal, you wouldn’t know how many you’ve actually absorbed.

For instance, in one study scientists determined how many calories participants had absorbed from almonds and compared these results to the standard method of calculating calories in food.

This method — called the Atwater general factor system — works out the calorie contents of foods by measuring their carbohydrate, fat, protein and fiber contents.

The researchers found that, on average, participants in the study absorbed 32% less energy than the calories estimated by the Atwater method. And individual participants’ responses varied significantly, ranging from an absorption of between 56 and 168 calories from 1 ounce of almonds — that’s a difference of 3x, which means that some people will absorb almost three times as much caloric energy from, in this case, almonds.

Which brings us to…

Food structure matters

So, at this point we’ve determined that you’re unlikely to know how many calories are in the food you’re eating, nor do you know how much of that caloric energy is being absorbed. But there’s another issue — the structure of the food, for it affects how many calories you get from the food consumed.

Let me illustrate this with an odd example to make a point. Imagine you swallow a hollow marble filled with 500 calories of chocolate.

The marble won’t get broken down in your gut, and therefore the chocolate inside won’t be absorbed. This means that both the marble with its chocolate content will be excreted in your stool, leaving you with zero calories from consuming it.

The point I’m making is that not all the energy in food is always available, something you might have experienced if you eat corn on the cob or sunflower seeds, bits of both of which you inevitably will see in your stool. This means that you can eat the same number of calories corn calories from corn on the cob and tortilla chips, but given their respective structure, you’re unlikely to absorb the same number of calories from them.

This is because corn on the cob and tortilla chips do not have the same food structure, and to confound things further, another reason to stop counting calories to lose weight pertains to something called the “food matrix”.

What’s the food matrix?

The food matrix includes the food’s structure — how it’s held together — and adds the compounds the food contains.

The food matrix helps explain why fruit juice is less healthy than whole fruit.

Fruit juice is high in fructose, and can cause a rapid increase in blood glucose levels which needs to be processed by the liver. A diet that is high in fructose may cause the liver to be overwhelmed, leading to problems such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes.

In contrast, whole fruit contains fiber. Fiber will slow down the absorption of the fruit carbohydrates, and cause a smaller glucose spike, while helping you feel full, even while eating fewer calories.

People tend to consume more calories when drinking fruit juice than they would eating the fruit itself. For instance, two cups of apple juice contains approximately 235 calories, whereas one medium-sized apple has about 100 calories.

Eating the apple instead of the apple will probably be more satiating due the fiber content, and be much more healthy.

Another example of the food matrix comes from examining the difference between absorption of variations of peanuts.

In a 1980 study, researchers gave participants whole peanuts, peanut butter, or peanut oil. They found that when people ate whole peanuts, they excreted more fat than the other participants. This means they absorbed less of the fat — and its calories. Those who consumed the peanut oil pooped out the least amount of fat, so they absorbed the most calories.

More than two decades later, a study published in 2007 presented a similar conclusion: Those who ate the peanut oil absorbed more energy.

The reason this occurs is that a lot of the fat in nuts is trapped within cell walls that neither your gut bacteria, nor the digestive enzymes in your stomach, small intestine and pancreas can break down.

In effect, then, that peanut is like that chocolate-filled marble ball: if your body can’t get at the caloric energy, it passes through you. But what if that marble was crushed by processing, or to be more realistic, since you’re unlikely to be eating chocolate-filled marbles, what if the cell walls of peanuts are destroyed by processing? When that happens, the caloric energy is absorbed and is made available to the body.

Food labels don’t capture these nuances, and you won’t either if you’re calorie counting.

The calorie counts for 100 grams of whole peanuts and 100 grams of pulverized peanuts would be the same on a food label, but in reality, you would likely absorb much fewer calories from the whole nuts.

The net of all this is that you typically don’t know how many calories the food you eat becomes available as caloric energy for your body to sustain itself.

OK, now that we’ve established that counting calories isn’t accurate, and so you should stop counting calories to lose weight, let’s turn to why calorie counting — even if accurate — wouldn’t help you manage your weight.

Macronutrients and food quality trump “calories in/calories out”

Research has shown that the type of macronutrients in food and food quality make a difference when it comes to weight loss and overall health.

For instance, a review on the topic explains:

“High-protein and/or low-carbohydrate diets do yield greater weight losses after 3–6 months of treatment than do low-fat diets.”

The authors observe that even when people consume roughly the same number of calories, the amount of weight they lose depends on the macronutrient contents of their diets.

It’s the macronutrient composition of the calories that make the difference.

For instance, nuts, avocados, and olive oil are well-known for being high in calories. A large avocado (322 calories), for instance, has a similar calorie count to a MacDonald’s cheeseburger (313 calories), but despite that, one is unequivocally better for you than the other (guess which one), underscoring that the quality of the food is what’s most important.

The number of calories in a food doesn’t tell you anything about the other nutrients it has, how good it is for your gut microbiome, how quickly it gets absorbed, or how many additives, preservatives, antibiotics or hormones it contains.

Clearly, 200 calories from a handful of walnuts does not have an equivalent impact on your body as does 200 calories from soda, or some other ultra-processed foods.

The soda and cheeseburger will provide next to no nutritional benefits (except some protein from the burger). The avocado and walnuts, on the other hand, offer important vitamins and minerals, fiber to fuel your gut microbiome, antioxidants and more.

The dangers of ultra-processed foods

The uselessness of counting calories to lose weight is further illustrated by the prevalence of ultra-processed foods in our diet.

Ultra-processed foods are manufactured “foods” that go through multiple processes (extrusion, molding, milling, etc.), contain many added ingredients, and are highly manipulated. Popular examples are soft drinks, chips, chocolate, candy, ice-cream, sweetened breakfast cereals, packaged soups, chicken nuggets, hotdogs and fries.

In many Western countries, ultra-processed foods make up a considerable chunk of the diets of those who live there. In the United States and United Kingdom, they account for more than half of the population’s energy intake, and even more in children.

It’s increasingly clear that ultra-processed foods play an important part in weight gain. A 2020 study, Ultra-processed foods and the development of obesity in adults, examined nine studies among different populations worldwide that showed a positive correlation between ultra-processed foods and obesity.

One of the nine studies showed a causal relationship between greater energy intake and weight gain due to the consumption of a high ultra-processed food diet.

The mechanisms by which ultra-processed foods are thought to increase the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes include increased energy intake (calories) due to increased sugar consumption, decreased fiber consumption, and decreased protein density.

Of course, you need to eat a lot of ultra-processed foods to become metabolically dysfunctional. Unfortunately, that’s what’s happening more than half the population, as mentioned.

Ultra-processed foods are made to be hyper-palatable; meaning, you don’t want to stop eating them, because they’re scientifically designed not to be satiating or nutritious, but to appeal to your taste buds. So, you look at the label and think, Hey, one serving is only 200 calories, but do you stop after eating one serving?

Too often when counting calories, we tend to fixate on the calorie figures alone. This can mean choosing foods simply because their calorie counts are low. And when you choose to eat ultra-processed snacks, self-delusion sets in.

You scan the food label and note that one serving is only 200 calories, a pittance, you think. But what goes unnoticed is how little “food” is in one serving; you wind up eating three or more. Now, perhaps unwittingly, you’ve consumed more than 500 calories — more than the very number you’re trying to reduce from your daily caloric count if the objective is to lose one pound per week (500 calories x 7 days = 3,500 calories, or one pound, more or less).

You’d be much better off eating 200 calories worth of almonds, or that small/medium avocado — both are more satiating and healthier.

Disordered eating

By now, we’ve established that calorie counting is far from the best way to lose weight. This is particularly true for those people prone to disordered eating.

Disordered eating refers to behaviors that are part of eating disorders. Some examples include compulsive eating, binge eating, and chaotic eating patterns.

This was made evident in a 2017 study (My Fitness Pal caloric counter) that recruited participants with existing eating disorders and had been using an app that counts calories and other health data. Around three-quarters of the participants reported that the calorie counting app contributed to their eating disorder.

Now, I want to acknowledge that studies that rely on self-reporting from participants are often not accurate, simply because there’s a lot of error about how people remember, estimate and report what they’ve done or didn’t do. However, the Fitness Pal critique was affirmed by another study from the same year (2017) that identified links between calorie tracking apps and increases in disordered eating.

Although researchers are still investigating this relationship, evidence is mounting that calorie counting apps are bad news, especially for people susceptible to disordered eating.

Alright, perhaps I’ve convinced you to stop counting calories to lose weight, but what’s a better option?

Stop Counting Calories to Lose Weight. Instead, Focus on Food Quality and Hand-sized Portions

There are two programs that have proven success helping thousands of people reduce body fat without counting calories: ZOE and Precision Nutrition.

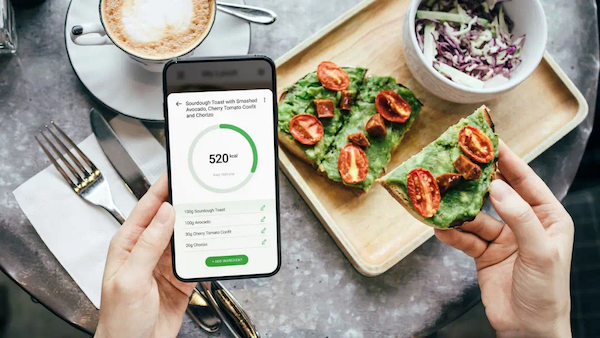

ZOE is a personalized weight loss/health coaching program based on its analysis of your unique gut, blood fat and blood sugar responses to food. ZOE is best for those who need help.

Precision Nutrition is specifically designed for health practitioners, but their Portion Control Guide can successfully put you in control of what and how much you eat. Precision Nutrition can help those who are self-motivated and disciplined, and don’t have health issues to contend with.

ZOE: A personalized nutrition program from the world’s largest nutrition-science study

ZOE’s personalized nutrition program is run by Professor Tim Spector, Scientific Co-Founder of ZOE, and Professor of Epidemiology, Kings College London.

ZOE aims to help you achieve your best health and healthiest weight for life. The company runs the largest nutrition study of its kind, which has given them deep insights about how everyone is different, and thereby respond to foods differently. They’re all about personalization — they have no one-size-fits-all approach to weight loss.

ZOE believes that the most important thing you can do to help reach your long-term health goals is to focus on food quality and ignore calories. Their research shows the best approach to achieve that is to eat a diverse range of plant-based foods. Professor Tim Spector suggests aiming for 30 different plants each week.

Rather than focusing on removing things from your diet, the ZOE approach is to focus on adding vegetables, nuts, seeds, whole grains, legumes, and fermented foods.

The best way to get your arms around what ZOE has to offer is to watch the following detailed review done by Lara Hyde, PhD. If you like what you see, you can use her link and the code LARA 10 to get a 10% discount.

If you want to dip your toe into the ZOE waters, get started with their quiz.

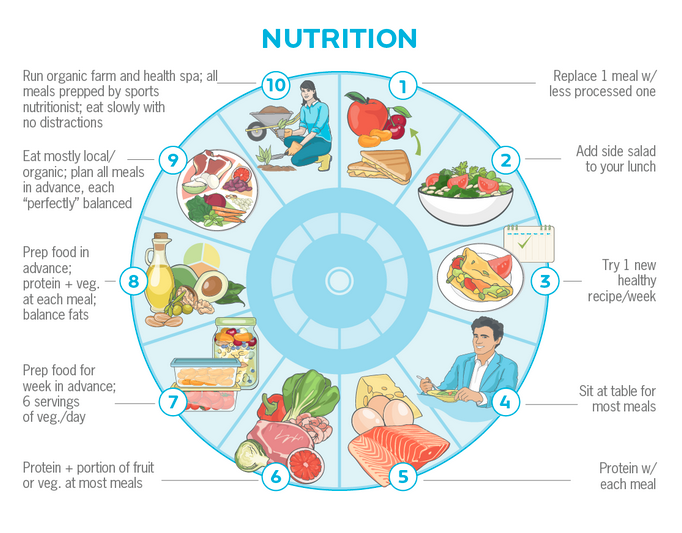

Precision Nutrition: Science-based nutritional guidance, primarily aimed at health practitioners

Precision Nutrition was founded by John Berardi, PhD and Phil Caravaggio in 2005 to train health professionals to offer nutritional and diet programs to their clients. But you don’t have to be a health practitioner to benefit from what they offer, because their website is replete with insights and guidance about how to best fuel your body.

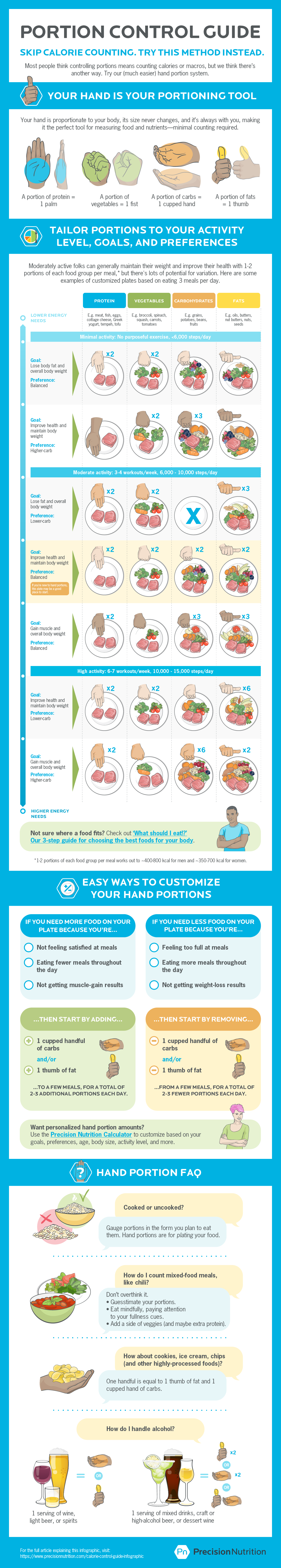

One innovative approach they’ve developed is a portion control method using your hand to measure the quantity of food to consume. With this approach, you can stop counting calories to lose weight and instead be guided by the size of your hand.

This method might sound weird, but as they say, “It’s practical, powerful, and proven with over 100,000 clients.”

This infographic from Precision Nutrition tells the tale:

Questions about this Portion Control Guide? See this FAQ

I'm curious to know what you think of this "hand method" for selecting food quantity as opposed to counting calories. Let me know in the Comments section below (just scroll down).

Your Takeaway

We went through all the many reasons why you should stop counting calories to lose weight. They pretty much distill down to:

Counting calories is not an effective way to know the caloric energy you’re actually getting from food, because you won’t get an accurate count, and striving to do will set you up to fail.

Instead of counting calories, do this:

- Pay attention to food quality — eat whole foods that are not adulterated (ie: look like they come from the farm, not the factory).

- Pay more attention to foods that can satiate rather than titillate your taste buds (ie: ultra-processed foods). Remember, ultra-processed foods are made to make you fat, because their made for you to overeat them, as well as to be metabolically disruptive.

- Rather than count calories, try the hand-based portion control method (the infographic above), or if you need personalization and coaching, investigate ZOE (scroll up and watch the video).

That’s it… over and out!

Last Updated on February 7, 2024 by Joe Garma