Metabolically Unfit? Most Americans Are!

Metabolically unfit? Quick question, long answer — to know you have to do some tests. Unfortunately, the odds are that you’re metabolically unfit, because only about 12% are not. Here I cover why it’s so important that you regain metabolic fitness if you want to live long and healthy.

About 88% of American adults are metabolically unfit!

That sounds preposterous, but that’s the findings of a recent, carefully constructed study.

In very basic terms, metabolism is the process of making fuel your body can use from the food you eat. If your metabolism does not work well, neither will you.

Metabolism is a lot more than a simple measure of how quickly our body uses calories to make energy. Metabolism is actually a collective term for the many processes that convert food and nutrients into energy and building blocks the body needs.

People often erroneously think that even though they’re eating the same amount of food as when they were young and trim, their metabolism has slowed down and is responsible for weight gain.

Usually, that’s not the case.

You’re fooling yourself if you throw up your hands and say, “Hey, I’m getting older so my metabolism is getting slower!”

Age is not the problem, until perhaps your 60 or over. A rigorous study conducted by researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Gillings School of Global Public Health found that metabolism remains stable in adulthood from 20 to 60 years of age.

We’ll return to this study later to see what typically happens to metabolism after age 60.

In this post, I'm going to:

Remember, you can not live the long and strong life you want if you’re not metabolically healthy. Find out where you stand, and what you might need to do.

88% of American Adults Are Metabolically Unfit

Let’s begin by erasing an excuse about metabolism. If you’re younger than 60, it’s not your “old and slow” metabolism that’s making your fat.

A study published by over 70 scientists in the journal Science in 2021 (abstract) investigated the effects of age, body composition, and sex on total expenditure and its components on 6,421 geographically and economical diverse people, aged eight days to 95 years old (full study pdf).

It found that total and basal expenditure and fat free mass were all stable from age 20 to 60. At age 60 and above, however, total and basal metabolism began to decline, along with fat free mass.

Yes, basal metabolism declined, because so did fat free mass — meaning, muscle mass declined and fat mass increased and both of those make you less metabolically active.

OK, you over-60 year olds know now that there’s a reason your metabolism has slowed down, and you youngsters can no longer blame a slow metabolism based on age. Now the question is: What are you going to do about it?

As I’m going to describe in detail, doing something about it is very much in your best interests. And that’s true even for you youngsters, because the truth is, according to researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Gillings School of Global Public Health, only 1 in 8 Americans is achieving optimal metabolic health.

That’s a dismal 12% of the U.S. population that is metabolically healthy. And I doubt that the rest of the world’s population is doing much better. So, odds are, you’re metabolically unfit. If true, that’s a problem.

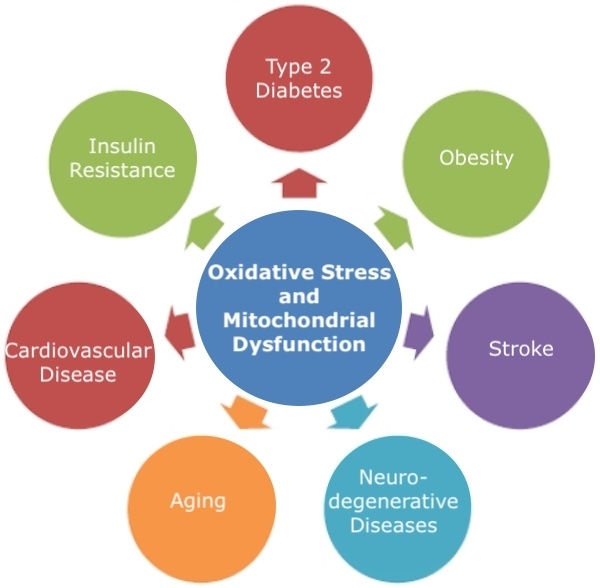

Poor metabolic health leaves people more vulnerable to developing Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and other serious health issues, which can be attributed to Metabolic Syndrome.

The findings of that North Carolina study was eye-opening and concerning. In its review of the study, the university’s website reports that only 27.3 million adults are meeting recommended targets for cardiovascular risk factors management — that’s out of about 258 million adults in the USA.

We’re going to dive deeper into this study in a bit, because it sets the stage for very problematic metabolic dysfunction. As you’ll soon learn, if your metabolism isn’t healthy, then all nine of the Aging Hallmarks set forth in the pivotal 2013 study on aging are going to exacerbate and contribute to shorten your healthspan as you grapple with one or more chronic diseases.

So, are you metabolically healthy?

The North Carolina study suggests the odds are that you’re not, as it concludes that the:

Prevalence of metabolic health in American adults is alarmingly low, even in normal weight individuals. The large number of people not achieving optimal levels of risk factors, even in low-risk groups, has serious implications for public health.

The purpose of this research is to determine the number and proportion of American adults who have optimal levels of each of five traditional cardiometabolic risk factors in the absence of pharmaceutical treatment.

The researchers are not saying that metabolic health is just the absence of Metabolic Syndrome, but how good are the biometrics associated with each measure.

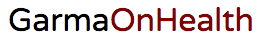

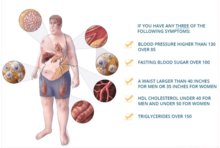

Let’s begin with understanding a bit about Metabolic Syndrome. It’s defined by the prevalence of any three of these symptoms:

If you have any of those three, you have metabolic Syndrome, which means you’re metabolically unhealthy and are likely to experience accelerated aging. (I’ll get to the aging part in a bit; for now, let’s stick to metabolic dysfunction.)

In slight contrast to biometrics presented in the illustration above, the researchers used the most recent guidelines to identify the cut off points for the five metabolic risk factors, which are slightly different.

Those participants who had these metrics or better were considered metabolically healthy:

- Systolic/diastolic blood pressure <120/<80 mmHg

- Fasting Glucose and HbA1c : <100 mg/dL; <5.7%

- Waist Circumference men/women: <102/88 cm (40/35 inches)

- HDL-C men/women: 40/50 mg/dL

- Triglycerides: <150 mg/dL

As you would expect, a range of outcomes came from the cohort of 8,721 participants studied. These were aggregated into various ” cut points” selected from prominent scientific societies and government agencies.

These were the percentages deemed metabolically healthy at the various cut points used:

- Overall prevalence of metabolic health was 19.9%

- With fasting glucose at 100 mg/dL or less it decreased to 16.0%

- Adding HbA1c to fasting glucose reduced it to 14.8%

- Blood pressure lowered from reduced it to 12.2%

(Note: HbA1c is an average level of blood sugar over the past two to three months.)

That last cut point, adding blood pressure to the mix, reduced the percent of metabolically healthy to a dismal 12.2%, which corresponds to only 27.3 million American adults!

“Metabolic syndrome is a serious health condition that puts people at higher risk of heart disease, diabetes, stroke and diseases related to fatty buildups in artery walls (atherosclerosis). Underlying causes of metabolic syndrome include overweight and obesity, insulin resistance, physical inactivity, genetic factors and increasing age.”

Let’s next address that “increasing age” bit, and then check out how you may find out if you’re metabolically healthy or not.

Mitochondria Age Is Accelerated If Metabolically Unfit

What is mitochondria and what does it have to do with metabolism and aging, you ask?

That’s a tough question to unpack, but let’s give it a whirl.

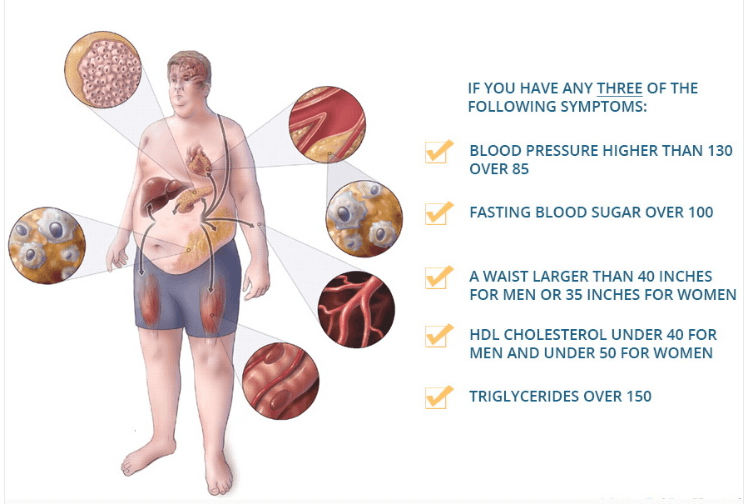

Mitochondria are membrane-bound cell organelles that generate most of the chemical energy needed to power the cell’s biochemical reactions. This chemical energy produced by the mitochondria is stored in a small molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is the fuel our cells need for energy; without it, we’re dead.

After the food and drink you eat is digested and thereby broken down into small molecules, a process called cellular respiration breaks down these molecules further so that eventually ATP is made, mostly inside the mitochondria (which is why they’re often referred to as the cell’s energy factory or powerhouse), and some in the cytoplasm of the cell.

Given that mitochondria are cell organelles, they reside inside cells. And like cells do, mitochondria have their own DNA.

We tend to think about metabolic health in terms of the five biometrics reviewed above, but these in turn are influenced by the health of our mitochondria and it’s ability to make ATP. Dysfunctional mitochondria do not produce the ideal amount of ATP required for nearly every factor that contributes to health; rather, it could produce too much or too little.

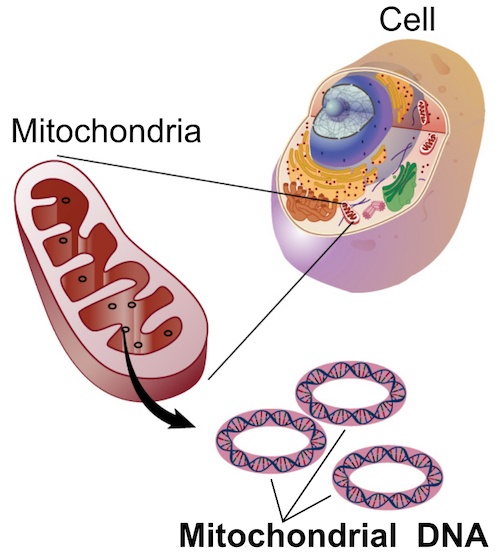

Mitochondrial dysfunction is involved in the pathophysiology (the disordered physiological processes associated with disease or injury) of a variety of metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders affecting important body organs including brain, muscles, eyes, heart, liver, and pancreas in varying levels of severity.

Mitochondrial dysfunctions are also recognized as major factors for various diseases including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, neurological disorders, and a group of diseases so-called mitochondrial dysfunction related diseases.

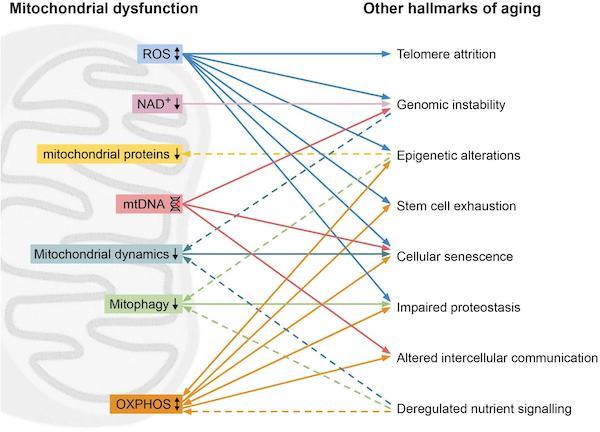

Given all this, it’s unsurprising that mitochondria dysfunction contributes to accelerated aging. It is one of the nine hallmarks of aging, and is interconnected to all of them.

Click here to read the sciency explanation

Mitochondrial dysfunction (left) and its relation with other hallmarks (right). High levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS, blue) can lead to telomere attrition, genomic instability, epigenetic alternations, stem cell exhaustion, cellular senescence. On the other hand, ROS can also improve proteostasis. Low levels of NAD+ (pink) can lead to genomic instability. Epigenetic alterations can lead to reduced mitochondrial proteins (yellow) such as STEAP2, RHOT2, and RAB32. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage (red) can result in genomic instability, cellular senescence and altered intercellular communication. Hallmarks of aging genomic instability and deregulated nutrient sensing can lead to reduced mitochondrial dynamics (turquoise), while reduced mitochondrial dynamics induces cellular senescence. Reduced mitophagy (green) leads to impaired proteostasis, while epigenetic alterations and deregulated nutrient sensing induce reduced mitophagy. Oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS, orange) affects the hallmarks epigenetic alterations, stem cell exhaustion, cellular senescence, impaired proteostasis, altered intercellular communication and is in turn affected by deregulated nutrient sensing, epigenetic alterations and impaired proteostasis. Dashed line represents an effect of a hallmarks of aging on the mitochondrial dysfunction.

What I’m trying to impress upon you is that your metabolism matters all the way down into those teeny tiny organelles within your cells that enable you to breathe and move by making ATP.

Next up are a few ways to test your metabolism.

Test Your Metabolic Health

I’m going to show you three ways for you to test your metabolism:

- Calculate your Total Daily Energy Expenditure

- Test if you’re insulin sensitive

- Examine your annual blood tests

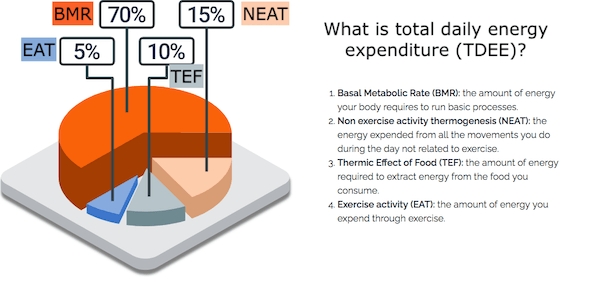

1. Total Daily Energy Expenditure

I wrote about how to test your basal metabolism in the post, How To Speed Up Your Metabolic Rate. Now, let’s look at the whole enchilada as depicted by the above image.

What we’re going to do is use a Total Daily Energy Expenditure Calculator to calculate your total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) using your age, sex, height, weight, and activity level. This includes not only your basal metabolic rate, but the energy used to produce thermogenesis, the thermic effect of food and exercise activity. As you’ll soon see, the calculator also estimates your Body Mass Index (BMI).

As I explained in my post How Much Should You Weigh? Calculate Your Ideal Body Weight, BMI does not account for an individual’s lean body mass. If you exercise regularly and thereby have less fat or more muscle than the average bear, then your BMI number will be inaccurate. For instance, mine puts me in the “overweight” category, and although I don’t have a six-pack, I ain’t overweight.

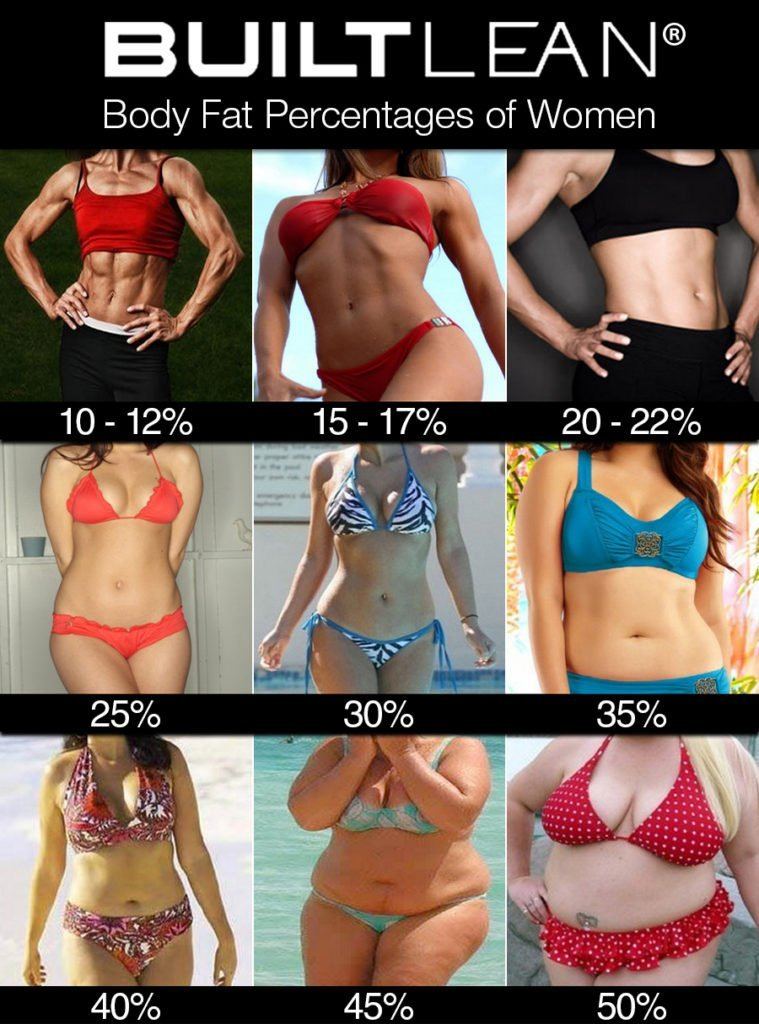

If you’d like to challenge the validity of a BMI number that you think is too high, go look in the mirror. Actually, I’m not (for a change) being cheeky. Let me explain.

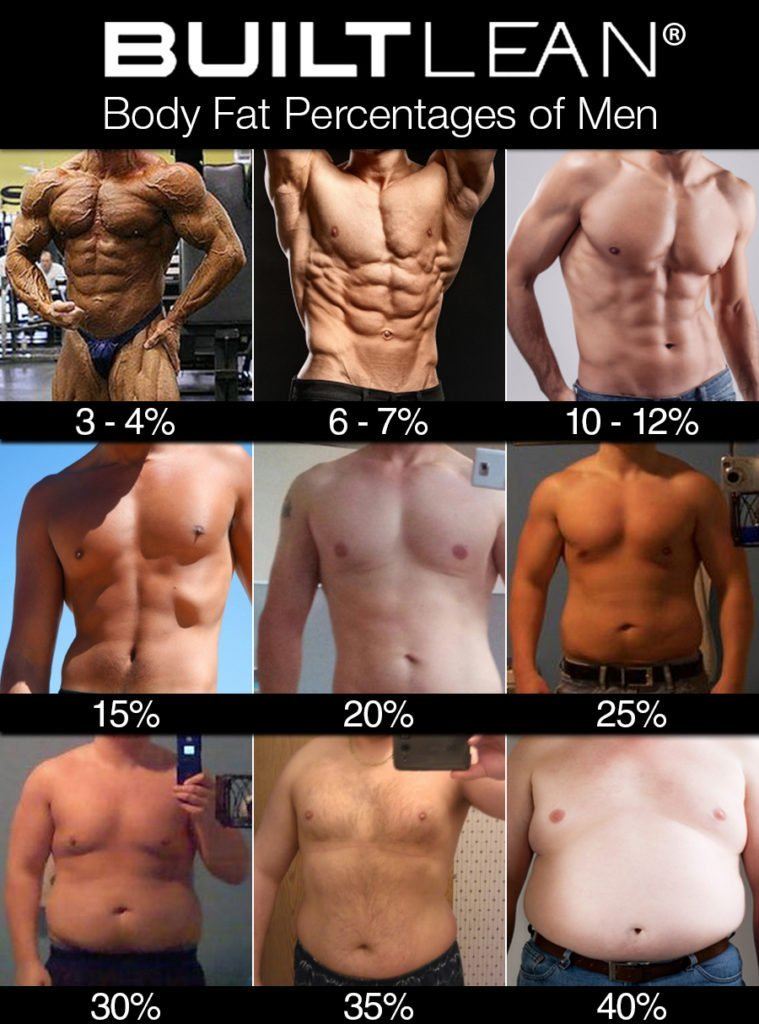

There are various ways to measure body fat, but assuming you’re not self-delusional, the easiest way to approximate it is to (A) look in the mirror at your near-naked body, and (B) see which of the following pictures that image in the mirror approximates.

For women:

For men:

In my case, my BMI is calculated to be 25.3, which is classified as overweight. But eye-balling the pictures above, I’d say that my body resembles somewhere in between 15 and 20% body fat.

This is verified by the Army Body Fat calculator (below). Typing in my gender, age, height, neck and waist circumference, the calculator cranks out a body fat number of 16.87%, right dab in the middle of those two pictures I referenced.

So, do this:

- Select the picture that most resembles the body fat you see in the mirror

- Use the Army Body Fat calculator to verify what your eyes suggest

- Then use the TDEE Calculator to check your Total Daily Energy Expenditure and validate, or not, the BMI number it calculates

Why be so concerned about the BMI calcuation of TDEE?

Frankly, for most people the BMI number is pretty accurate, because most people don’t exercise enough to have more muscle mass than what the BMI accounts for. But if you’re one of the rare ones that have more lean body mass than what the BMI estimates for your age, height, body weight etc., then you can afford to consume a bit more calories than the TDEE calculates, assuming you accurately portrayed your activity level that the calculator requires. The reason for that is — muscle is more metabolically active than fat.

Because muscle is more metabolically active than fat, the more muscle you have, the higher your basal metabolic rate — how many calories you burn whilst doing nothing. Also, the more muscle you have (assuming you don’t also carry a lot of body fat), the less likely it is that you have any of the three of five metabolic symptoms symptomatic of metabolic syndrome.

Further, as this study underscore, exercise can regulate mitochondrial respiration, thus affecting ATP production and mitochondrial function. And this Denmark study affirms that regular endurance training increases the number of mitochondria in our muscles. This is why many endurance athletes have more than twice as many of these “powerhouses” as non-athletes.

The bottom line here: You can improve your metabolism by adding muscle to your body, and cutting the fat.

2. Are You Insulin Sensitive?

The primary instigator of metabolic syndrome and all of its underlying factors is insulin resistance! That’s the opposite of insulin sensitivity. What you want is for just a bit of insulin produced by your pancreas to do the job of shuttling glucose into your cells to eventually make ATP, primarily in the mitochondria, via the process of cellular respiration.

There are two ratios that can indicate if you’re insulin resistant:

I cover all of this in my post How to Test Your Insulin Sensitivity and Why It Matters, so do yourself a favor and check that box.

You may also check for insulin sensitivity with the NMR LipoProfile®, which is highly recommended by both Dr. Mark Hyman and Dr. Peter Attia (it’s one of his five important blood tests he recommends), and the Glucose Tolerance Test with Insulin.

3. The Metabolic Syndrome Tests

Of course, you can also get each of the five tests that are pertinent to metabolic syndrome, given that having any three of the five indicate you are metabolically unfit.

Again, the five with the desired results are:

- Systolic/diastolic blood pressure <120/<80 mmHg

- Fasting Glucose and HbA1c : <100 mg/dL; <5.7%

- Waist Circumference men/women: <102/88 cm (40/35 inches)

- HDL-C men/women: 40/50 mg/dL

- Triglycerides: <150 mg/dL

Your doctor should be covering all but waist circumference during your annual check-up, so rummage through your files and find your last blood test panel.

What To Do If You’re Metabolically Unfit

OK, you jumped through the hoops, did the tests and want to improve your metabolism… what should you do?

Go to my insulin post and see the details behind these suggestions:

- Eat foods with a low glycemic load

- Practice time restricted eating

- Exercise

- Reduce stress

- Supplement

How to make your insulin sensitive

Go to my basal metabolic post and see the details behind these suggestions:

- Get more sleep

- Tamp down the stress

- Don’t skip breakfast? (depends)

- Stand

- Eliminate junk food

- Exercise

- Lift weights

7 ways to speed up your basal metabolic rate.

Your Takeaway

Let’s whittle this down to some essentials.

Remember these three things:

(1) If you’re an American, odds are you’re metabolically unfit, since only about 12% of Americans are. (Big congrats if you’re not.) But no smirks if you hail from elsewhere, because if you eat like an American and don’t regularly exercise, assume you’re in the same boat.

(2) You can check the fitness of your metabolism by, presumably, examining your annual blood tests, measuring your blood pressure, waist circumference, height-to-waist ratio, insulin blood tests and the calculators placed in this post.

(3) You can improve your metabolism by — what else — diet and exercise. Eat more high-fiber foods, more plant food, less fast food, less processed food, and exercise more, especially exercises that build muscle.

Last Updated on November 8, 2022 by Joe Garma