“Why Controlling Glucose Is More Important Than Your Diet”, says Dr. Attia

Controlling glucose is more important than your diet, says Dr. Peter Attia, an anti-aging expert and biohacker, because it’s a key to longevity. Listen and read why blood sugar control — as well as sleep, meditation, protein intake and lifting heavy stuff –is important for a long healthspan.

YOU’RE GOING to learn a lot about controlling glucose and many more ways you can markedly improve your healthspan from two notable figures in the health and life extension world, Dr. Peter Attia and Chris Kresser.

Dr. Peter Attia is the founder of Attia Medical, PC, a medical practice that focuses on the applied science of longevity and optimal performance. The practice applies nutrition science, lipidology, four-system endocrinology, sleep physiology, stress management and exercise physiology to minimize the risk of chronic disease onset while simultaneously improving healthspan. The man knows of what he speaks.

Chris Kresser, M.S., L.Ac., is the creator of the ADAPT Practitioner and Health Coach Training Programs. He is one of the most respected clinicians and educators in the fields of Functional Medicine and ancestral health and has trained over 1,300 health professionals around the world in his unique approach.

Valuable insights are yours for the taking when these two come together.

In this article, we’ll cover:

- Dr. Peter Attia’s two longevity “Aha! Moments”;

- Why your death is likely to be from one of three chronic diseases;

- Why controlling glucose is more important than diet;

- What a glucose monitor revealed to Dr. Attia;

- Why poor sleep elevates stress and impairs your health and what to do about it;

- Why both Dr. Attia and Chris Kresser are champion meditation and prescribe it to their patients;

- Why Dr. Attia is a protein minimalist; and

- Why Dr. Attia does heavy deadlifts.

Let’s dig in…

What follows is the interview between functional medical expert Chris Kresser and longevity expert Dr. Peter Attia. If you have 55 minutes to spare, take a listen; otherwise, you can more quickly read my summary (along with several explanations and amplifications) below.

Dr. Peter Attia’s Two “Aha! Moments” About Longevity

In the interview, Dr. Attia tells Chris Kresser about how his approach to thinking about longevity (how to extend it) has evolved. His first “aha! moment” as he calls it happened when got the insight to rephrase the question from “How do I live longer”, to:

1. “When and how will I die?”

Dr. Peter Attia

This is an easier question to answer than “How do I live longer”, because the set of probable answers is smaller and easier to ascertain. To answer this question, you so some reverse engineering, says Dr. Attia. You examine the possibilities of how a person typically dies, and then address which of them is most likely to happen to you. (see “Death by Chronic Disease” below.)

The second “aha! moment” came from the insight of examining the attributes of long-lived people.

2. “Why do centenarians live so healthy so long?”

Centenarians die of the same chronic diseases as the rest of us, but it happens later in their lives. So, what what is it about them, about their genes, that delays the onset of chronic disease, Dr. Attia wondered?

If you listen to the interview, you’ll note that he doesn’t address this directly, but goes off on a long tangent about rapamycin, something he studies deeply.

Rapamycin is derived from a rare bacterium called Streptomyces hygroscopicus that has antifungal properties, and was made into a drug that helped organ transplant patients accept donor organs by suppressing their immune systems.

As I wrote about it in my article, Do These 2 Ant-aging Pills Really Work?, rapamycin has been demonstrated to induce autophagy by inhibiting the mTORC1 pathway, and thereby increase lifespan in various animals studied. The research indicates that rapamycin can increase the lifespan in mice up to 30%, which has major implications for humans.

I think Dr. Attia got off on the rapamycin tangent because, as mentioned above, it induces autophagy, which is basically the process whereby our cells clean up various errors and assaults within themselves. This can only happen through various nutrient sensing pathway mechanisms inherent to cells and activated when fasting.

A 2012 study entitled, Extending healthy ageing: nutrient sensitive pathway and centenarian population, summarized it this way:

“Many of the genes that act as key regulators of lifespan also have known functions in nutrient sensing, and thus are called “nutrient-sensing longevity genes”. Some examples of nutrient-sensing pathways involved in the longevity response are the kinase target of rapamycin (TOR), AMP kinase (AMPK), sirtuins and insulin and insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) signaling.”

Turns out, that centenarians have more genes than the rest of us that upregulate nutrient sensitive pathways that favor longevity and downregulate those that don’t.

You can learn more about nutrient sensing pathways and how they’re activated by fasting and fasting mimicking diets, like ProLon, in my review of Dr Mark Hyman’s interview with Dr. Vlater Longo, the inventor of the Prolon Mimiking Diet.

Death by Chronic Disease

Dr. Attia makes the point that if you exclude smokers, people under 40 years of age, accidental deaths and suicides, then “70 to 80% of all deaths will be due to four diseases, or what I really think of as three disease processes”, which are:

1. Atherogenic diseases (heart disease and cerebrovascular disease).

2. Cancer/Neoplasm (An abnormal mass of tissue that results when cells divide more than they should or do not die when they should).

3. Neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease).

He believes the overarching theme behind these chronic diseases involve nutrient sensing. He says, “We go back to what we know about rapamycin and caloric restriction, and we ask, what is it doing?”.

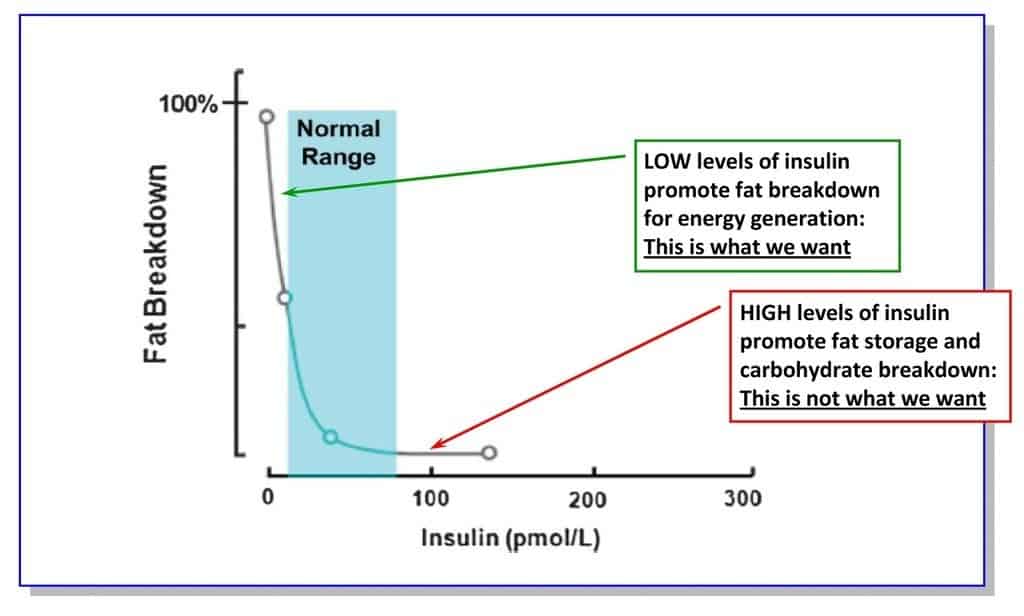

This is where you want your nutrient sensing signalling environment to be:

- Insulin is very low,

- IGF-1 is low,

- mTORC1 is low,

- AMP kinase is high, and

- GTPase is low

This is all controlled by the way you eat, sleep, exercise and manage stress.

Diet’s Not Important, Glucose Is

Here’s Peter Attia’s take on diet and glucose:

“I don’t really care about diet. None of that stuff interests me. I don’t care if you’re paleo, I don’t care if you’re vegan, I don’t care if you like South Beach or Atkins or Ornish. None of that stuff interests me. I’m really just interested in the biochemistry of these molecules, and given that different people can tolerate these molecules in different fractions, the name of the game is glucose disposal. Can you maintain a low average level of glucose and a low variance of glucose and a low area under the curve of insulin? Those are really the things I care about. Now the challenge is it’s not easy to measure those things. For me, it’s very easy because I wear a continuous glucose monitor.”

I repeat an important point he makes:

“… the name of the game is glucose disposal. Can you maintain a low average level of glucose and a low variance of glucose and a low area under the curve of insulin?.”

Let’s take a look at each of these.

Low average level of glucose

Your glucose level responds to the macronutrients you eat, mainly to carbohydrates, although protein does have a modest affect on glucose and fat even less.

In the past, there was little consideration given to the possibility that individual’s might have a different glucose response to ingesting macronutrients, and therefore, the Glycemic Index was the holy grail for controlling glucose, in that it indicated how you could expect different kinds of carbs to affect your blood sugar (glucose). Now, enlightened by studies such as those conducted by the Weizman Institute (see this article), we know that people’s glucose levels in response to various foods can be widely different.

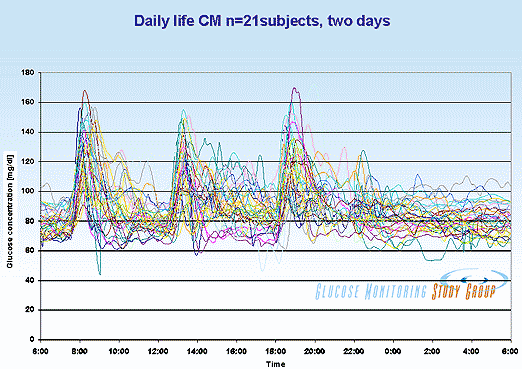

For some people, eating a banana and a bowl of Corn Flakes will spike their glucose levels for a sustained period of time (not good), and for others the impact is minimal (lucky folks). This graph, courtesy of Health Correlator, depicts these individual differences:

The above grows how each of 21 individuals has a unique set of responses to meals, which are represented by the three main blood glucose peaks. Overall, blood glucose levels vary from about 50 to 170 mg/dl (2.8 to 9.4 mmol/L), and in several cases remain above 120 mg/dl (6.7 mmol/L) after two hours since a large meal.

Despite these individual differences, unless you know from testing how your blood glucose reacts to ingesting various foods, I suggest you assume that your blood sugar’s reaction will vary closely to the norm, which means that you should favor unrefined, high-fiber carbs over refined, high-sugar carbs. Doing so gives you the best chance of mitigating high glucose spikes after eating and a low average glucose level.

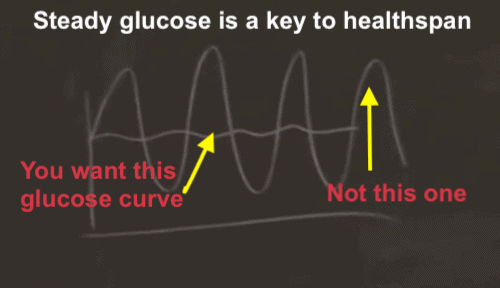

Low variance of glucose

“Variance” refers to “change”, and the objective is to bring the peaks of that graph above closer to the troughs. Eyeballing the three peaks indicates that they fall in the range of 150 to 170 mg/dL (8.3 to 9.4 mmol/L). The troughs look to range from 45 to 60 mg/dL (2.5 to 3.3 mmol/L).

The objective is mainly to lower the peaks, thereby lowering the variance, as this is a graph drawn by Dr. Attia shows:

Graph from my article, How You Can Increase Lifespan.

Low level under the curve of insulin

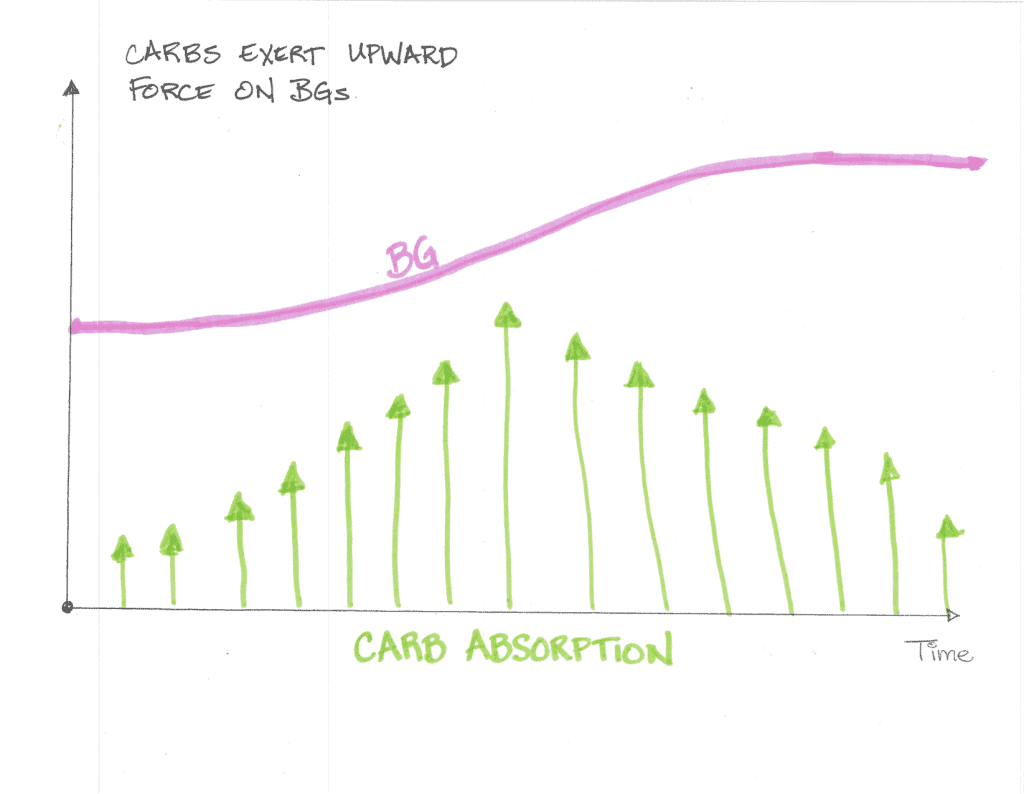

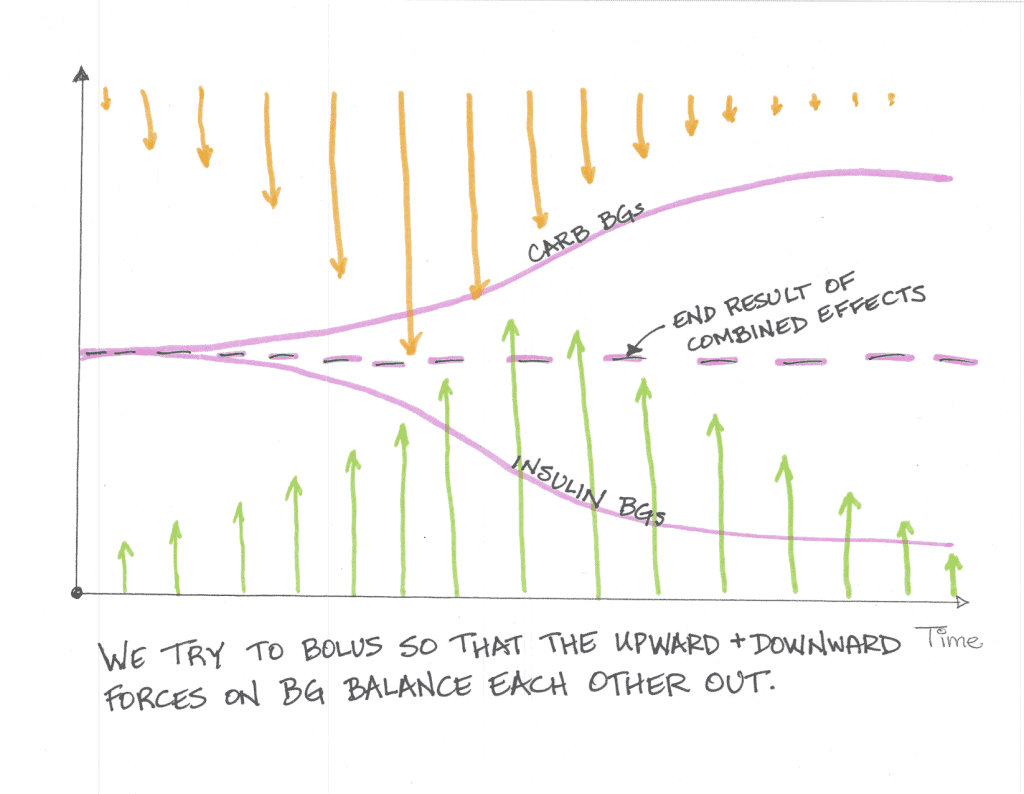

Continuing with hand drawn graphs depicting the insulin/blood glucose story, let’s turn to a series of such graphs by “” who writes for a diabetes site. In his article about “why the duration of insulin action matters“, the author illustrates the story with the following graphs (where “BG” refers to “Blood Sugar”).

In the following illustration (like the rest below are not to scale, but they do show what’s happening conceptually), blood sugar (BG) continues to elevate even after carb absorption peaks:

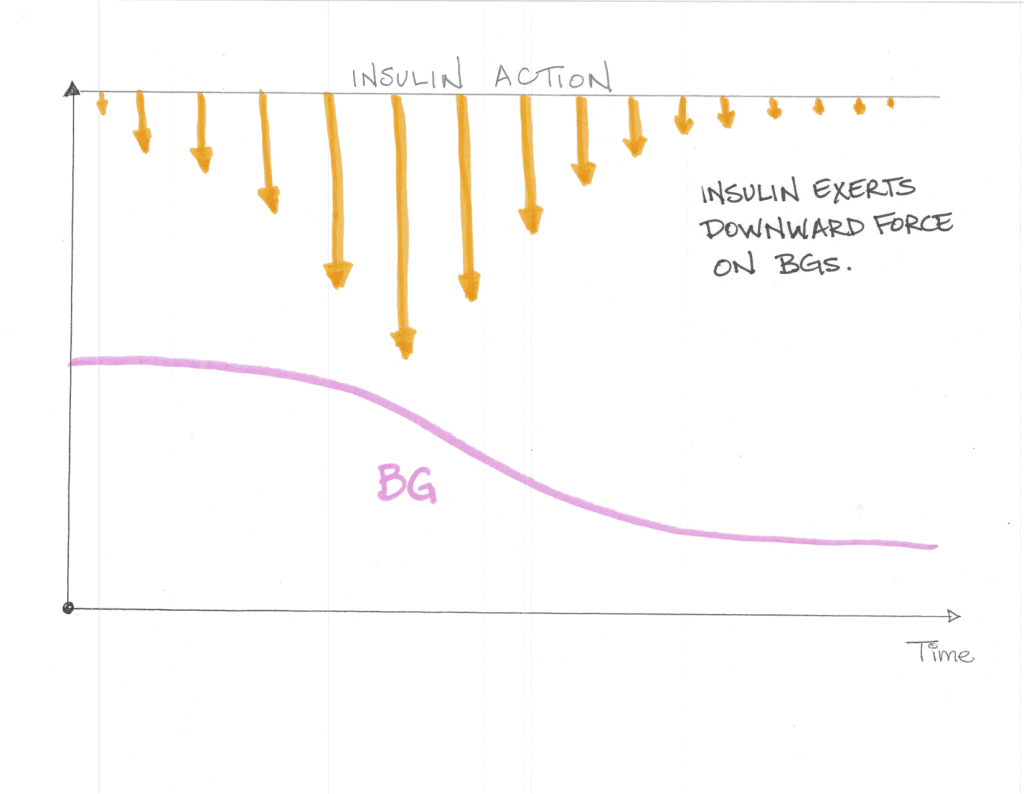

And insulin makes your BG go down:

Ideally, the net effect of insulin pushing blood sugar down and carbs pushing it up produces a fairly level glucose curve:

Ideally, the net effect of insulin pushing blood sugar down and carbs pushing it up produces a fairly level glucose curve:

What A Continuous Glucose Monitor Revealed to Dr. Attia

Very few of us have the luxury of controlling glucose by wearing a continuous glucose monitor, something that can show you what your blood sugar is at any moment. Instead, we typically either get a fasting blood sugar and average blood sugar (called the HbA1c test) once or twice a year when we see a doctor.

Those who have the ambition to manage their blood sugar, have type 1 or type diabetes, usually must prick themselves with a sharp-pointed “lancet” that’s part of a glucose monitoring kit. (I use this one.)

Dr. Attia uses a continuous glucose monitor. With it, he’s able to track his blood sugar response (in real time and continuously) as it responds to not only food, but to stress.

Stress will elevate glucose

During a period he was experiencing unusually high stress, Dr. Attia found that he would wake up with elevated glucose levels even though he had eaten nothing since the night before. Having not eaten for eight hours or so pretty much eliminated food as the source of the high levels of blood glucose his monitor was revealing. Dr. Attia concluded that stress causes his elevated blood sugar, which underscores the science on the matter. Controlling glucose would mean managing his stress.

Attia could predict when his glucose reading would be high in the morning based upon the quality of his sleep. (He measures various aspects of sleep with the Oura Ring, similar to the Motiv Ring available on Amazon.) “I found that it was actually pretty easy to temper that by using phosphatidylserine before bed to suppress adrenal output and therefore bring glucose down”, he says.

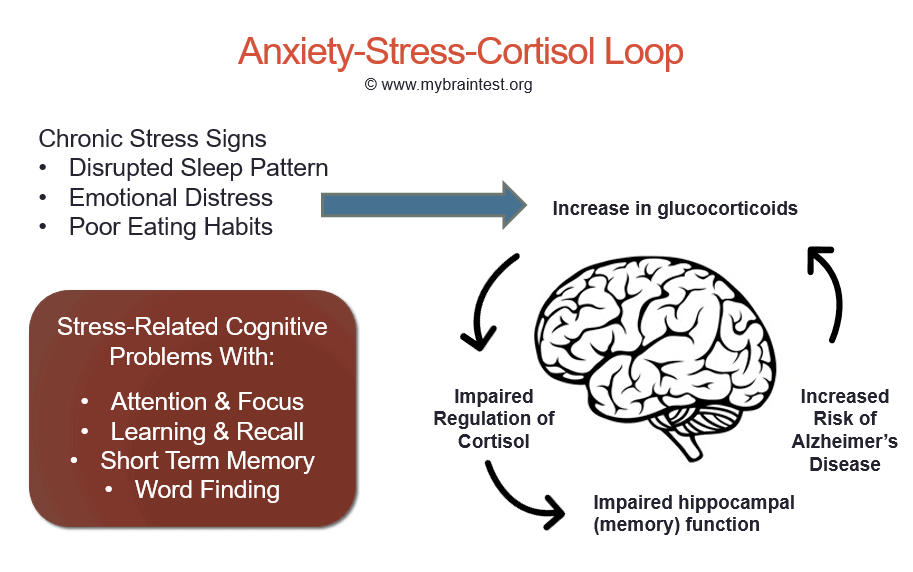

Click here for info on glucocorticoid cortisol's affect on stress and anxiety

BrainFacts.org tells us how glucocorticoids and cortisol impacts our health, both good and bad.

In response to signals from a brain region called the hypothalamus, the adrenal glands secrete glucocorticoids, which are hormones that produce an array of effects in response to stress.

These stress responses include mobilizing energy into the bloodstream from storage sites in the body, increasing cardiovascular tone and delaying long-term processes in the body that are not essential during a crisis, such as feeding, digestion, growth, and reproduction.

Some of the actions of glucocorticoids help mediate the stress response, while other, slower actions counteract the primary response to stress and help re-establish homeostasis.

Over the short run, epinephrine mobilizes energy and delivers it to muscles for the body’s response. The glucocorticoid cortisol, however, promotes energy replenishment and efficient cardiovascular function. Glucocorticoids also affect food intake during the sleep-wake cycle.

Cortisol levels, which vary naturally over a 24-hour period, peak in the body in the early-morning hours just before waking. This hormone helps produce a wake-up signal, turning on appetite and physical activity.

This effect of glucocorticoids may help explain disorders such as jet lag, which results when the light-dark cycle is altered by travel over long distances, causing the body’s biological clock to reset itself more slowly. Until that clock is reset, cortisol secretion and hunger, as well as sleepiness and wakefulness, occur at inappropriate times of day in the new location.

Acute stress also enhances the memory of earlier threatening situations and events, increases the activity of the immune system, and helps protect the body from pathogens. Cortisol and epinephrine facilitate the movement of immune cells from the bloodstream and storage organs, such as the spleen, into tissue where they are needed to defend against infection.

Glucocorticoids do more than help the body respond to stress. They also help the body respond to environmental change. In these two roles, glucocorticoids are in fact essential for survival.

Poor Quality Sleep Elevates Chronic Stress

Sleep is so important to reducing chronic stress that it’s worth exploring further.

When it comes to sleep, you need both quality and quantity. Sleep of insufficient duration (less than seven hours) or quality (tossing, turning, frequent awakening) can significantly impair everything in your life.

- In the short term, a lack of adequate sleep can affect judgment, mood, ability to learn and retain information, and may increase the risk of serious accidents and injury.

- In the long term, chronic sleep deprivation may lead to a host of health problems including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even early mortality.

In his clinical experience, Dr. Attia thinks that “sleep is pretty easy to fix once the patient buys into why they need to fix it, and actually I find, frankly, that’s probably the biggest challenge.”

Here’s Dr. Attia’s sleep formula:

- Keep the room completely dark (I use this sleep mask)

- Keep the room cold (reason?)

- Refrain from looking at blue light emanating from computer, TV and phone screens before bedtime (unless wearing these glasses)

- In the evening before bed, try:

- Melatonin (Dr. Pierpaoli’s brand is good),

- GABA and/or Phosphatidylserine (provided you have a magnesium transporter like L-threonate to get into the central nervous system),

- Vitamin D3 , and

- Magnesium (unless you’re already using L-threonate.)

Meditation Reduces Chronic Stress (and more!)

Both Dr. Peter Attia and Chris Kresser are in love with meditation, because they’ve observed the multi-faceted benefits, both hand in their respective clinics and personal practice.

Says Attia:

“Speaking of stress… where there is more research on this than I could have ever imagined if I hadn’t looked into a year ago, is in the area of transcendental meditation… The effects on blood pressure, on cortisol, on glucose, on metabolic factors—I think it’s real.”

To which Chris Kresser responds:

“My sleep, my attitude, my mood, my exercise recovery, my mental and cognitive performance, my digestion. There’s no single intervention that I’m aware of that can have an effect over so many different parameters in my life, and I’ve learned that time and time again, so the research doesn’t surprise me at all.”

Many who try meditation can’t sit still, even for ten minutes, or still their chattering thoughts. My suggestion:

Try binaural beats and/or isochronic tones

These are sounds you would hear wearing stereo headphones. They work through something called “brain entrainment”. For more on this, read my article, Meditate Like A Monk In 20 Minutes. You can find these tones on YouTube.

Why Dr. Attia Is A Protein Minimalist

If you had to overdo it with either protein or dietary fat, which would you choose?

It wasn’t too long ago that I would have chosen excess protein, but as Dr. Attia explains, the healthier option would be to choose excess dietary fat because of IGF-1.

I dug pretty deeply into the IGF-1 story in my review of Dr. Mark Hyman’s interview with Dr. Valter Longo,

Can The ProLon FMD Reverse Disease and Extend Lifespan?. Suffice to say that:

To prolong our lifespan, the goal is to keep up a relatively low IGF-1 throughout most of our adult life, and then as we get into our eighties and beyond, to consume enough protein so that our IGF-1 level does not get excessively low.

For Dr. Attia, “enough protein” is the minimum amount to retain muscle mass. Eating much more protein than that, particularly when older, is likely to increase IGF-1 too much. The reason for this is that most of our protein comes from animal sources and animal protein contains a lot of methionine, which increases IGF-1. Thus, you can eat less animal protein in favor of more plant protein, or reduce your consumption of protein overall.

Dr. Attia puts it this way:

“What I’m telling my patients is really you only need as much protein as is necessary to preserve muscle mass. That’s sort of the goal. The goal is muscle mass. That’s the name of the game. So when we’re seeing nitrogen balance as positive, we’re overdoing it. You can see now you have a sliding scale, which is carbohydrate goes up until you hit your glucose and insulin ceiling, protein comes down until you’re about to erode into muscle mass and slip into positive nitrogen balance, and then fat becomes the delta [the difference]. So in somebody like me, that’s probably about a 20% carb, 20% protein, 60% fat diet.”

Note that Dr. Attia’s macronutrient portions — 20/20/60 — is for someone that seeks to preserve muscle mass, rather than increase it. If you have never done resistance training in any form (calisthenics, weight lifting or HIIT) and thereby need to, or want to, build muscle —as opposed to simply maintaining what muscle you have — then consider increasing your ratio of protein to something like 30%, making the resulting macronutrient proportions something like this: 30/20/50.

To still manage IGF-1, focus on plants for your protein sources, such as legumes (soak overnight before cooking to reduce lectins and phytates), hemp/chia/flax seeds, nuts, etc. (see this list), plus veggie-based protein powders (pea, hemp, rice, sprouts).

Why Dr. Attia Deadlifts Heavy Weight

Peter Attia regularly swims, runs and bikes, so why is he convinced that he also needs to lift weights?

It has to do with managing glucose and maintaining muscle mass.

Among the lifts he does are deadlifts, and he does them heavy, around 350 pounds, quite a bit for a non-competitive, under 200 pound, forty-plus year-old.

He explains why he lifts heavy weights in recounting a conversation with a friend while they were both exercising at a gym, just after a set of deadlifts:

“Why the hell are you doing that?!” He’s like, “Is that really necessary?! You bike, you swim, you run. I mean, what is that possibly doing for you that those other things don’t do?” And I said, “Well, actually it is doing something for me that those other things don’t do. Those other things don’t activate my IIB muscle fibers, and that’s something I’m placing a high premium on.” It’s very hard to activate the type IIB fiber, and yet if I can get all of those fibers working—type I, IIA, IIAB, and IIB—I’m going to have a much more glucose-hungry muscle, I’m going to have much more mitochondrial activity, and frankly I think squats and deadlifts are the two most important exercises.” (Click here to learn about types of muscle fiber.)

Now, admittedly, Peter Attia devotes himself to optimizing nearly everything he does, and he’s on a mission to live as long and strong as he can. If you rather spend a few more hours on the couch than he does, you still can move the needle in the right direction when it comes to maintaining muscle as you age, and thereby prevent the dreaded sarcopenia.

Sarcopenia is the degenerative loss of skeletal muscle mass quality, and strength associated with aging. Unless you apply your muscle against resistance (body weight, weightlifting, etc.), you will lose between 0.5 and 1% of your muscle per year after age 50. Less muscle, less activity, more falling, more breaking bones.

Your Takeaway

We covered a lot of ground here, but it can be summarized in four things for you to remember and act on:

- You’re most likely to die from just three things, all of which increase in probability the older you get:

- Atherogenic diseases

- Cancer/Neoplasm

- Neurodegenerative diseases

- You can reduce your chances of succumbing to these diseases by controlling glucose, IGF-1 and the other nutrient-dependent sensing pathways by the practice of Intermittent Fasting, Fasting Mimicking Diets and plant-based proteins.

- Chronic stress ages you quickly. Sleep, meditation and exercise are powerful stress reducers.

- Maintain (or grow) muscle mass by lifting heavy things (you’re body weight is sufficient), which also helps control glucose.

Last Updated on July 7, 2023 by Joe Garma